On an August night in 1986, there had been a power outage in Trout River, and from sundown, a taper candle lit the room where Junie and her grandparents slept. As was their habit during that stifling time of the year, they abandoned the large bed they shared and instead moved to a bamboo mat in the middle of the concrete floor. In one corner of the room, a coil of mosquito-repellant incense was burning—a green galaxy shape with one of its ends glowing orange—and now it was shedding its third spiral trail of ashes on the floor, a timekeeper for the dwindling night.

Over their decades of life together, Junie’s grandparents had perfected a way of talking to each other in the dark, point counterpoint, and in a volume just below the threshold of waking up nearby children. The thoughts spun out this way sometimes went in separate directions, but they always found ways to intersect and stay in motion. They had talked in this way as their three sons grew up and as they left for other places, one by one, with families of their own. But these days, as the couple’s world shrank due to the tightening rein of old age, more often they talked about Junie; about Momo, who was the most far-flung of them all; and about Cassia, who they feared was slowly unraveling in America because she’d never written to them since arriving there. The only signal of her presence came at the tail end of Momo’s letters, where he always added something perfunctory about Cassia sending her greetings.

“It was a mistake to not let her see the baby,” Grandma said.

It was the first and only time she had summoned this thought aloud, something long dispatched into the abyss of Things Families Don’t Talk About. But tonight the oppressive heat made her mind less cautious, and it roved far and wide into the realms of What Was, What Will Be, and, along with it, What Might Have Been.

Beside her, Grandpa squinted as if trying to focus on something emerging from the darkness. With one hand, he flapped a fan over Junie’s sleeping body. With the other hand, he reached inside his mouth and tried to wiggle a decaying tooth loose. He knew that like the mosquito incense, the number of one’s remaining teeth was a kind of timekeeper too.

“What would have been the use?” he mumbled. “The ashes, that child—wasn’t even enough of it to fill up a can.”

*

The next morning, when the troublesome letter arrived, Junie woke up alone on the bamboo mat and found that it had imprinted its woven texture onto the skin of her arm. As she sat up and rubbed her eyes, the day’s moist breath was already waiting for her.

Junie washed her face and climbed onto her wooden horse to look for her grandparents, who turned out to be in the courtyard fetching water from the well. Grandpa hovered over the rim with an aluminum bucket tied to a rope, and flicked his wrist to plunge it bottom-up into the well, at the exact angle for its mouth to scoop up the water. With another tug and several pulls, the bucket was back in his hands, now heavy with its new charge. He poured the subterranean water into one basin to keep a watermelon chilled until the afternoon, and then into another containing vegetables Grandma was washing for lunch.

To Junie, this flow of movement and liquid sounds had a whiff of eternity about it, like a melody that you knew would eventually come back to itself and said that the world would always be just so.

The well was off-limits to Junie, of course, and she was only allowed to stand at a distance deemed safe by adults who’d seen how easily any body of water could swallow even an able-bodied child. But even just looking on from her vantage point on the wooden horse, the known world was somehow made intelligible by water, be it the well connected to the river, or the rain that always fell incessantly in the sixth month, or even the exhalation in the noonday air, which brought smells of vines and mushrooms from places she couldn’t see.

“There’s a letter from your dad and mom today,” Grandpa looked up to say. He hadn’t waited for Junie to ride with him to the market this morning.

Over the past five years, these letters came to Trout River in envelopes bearing stamps of foreign men with large foreheads. Junie read these letters out loud with her grandparents, but their content perplexed her. (Momo’s doctoral stipend got renewed; Cassia just arrived in San Francisco.) They were splices and pieces, with their connective threads missing.

Today when they cut open the envelope just before lunch, they found that inside, Momo included a separate sheet of paper addressed “Dear Junie,” the first time she had been singled out this way:

I promise you that we will be reunited here by your

twelfth birthday—just a year and a half away! Turning

twelve is a milestone in a person’s life, and we will

celebrate it all together.

For emphasis, he’d put dots under the two characters for the word “promise,” as if this had been a request on her part that he was granting.

Reunited—there? Junie looked up from the letter and sought the eyes of her grandparents, but their faces portrayed neither surprise nor confusion.

“They mean for me to visit, right?” Junie said. “Not to live with them there?”

There was a pause before Grandma answered: “Your mom and dad want to raise you themselves.”

The sound of the cicadas outside rose in volume and seemed to drift into a minor key.

“But why can’t I live here with you? Momo grew up here.”

A look passed between her grandparents. “Someday Grandpa and I will get old, you see, and won’t be able to take care of you.”

It was as if the world was going off-kilter, rearranging itself around her, without her. Junie had never thought that at some point in the future, she would sit down with her grandparents around this table for the last time.

“Then I will take care of both of you,” she said, “when you get old.”

Grandma began shaking her head as if she’d come to the limit of her explanatory powers, but she really hadn’t explained anything at all, Junie thought. They were asking her to submit to an order of things that she could not uphold as real.

Her grandparents cleared the table and put the leftover food under a mesh dome to keep the flies away. It was now that time of day when villagers young and old took noonday naps in any position and on any convenient surface available—tables, benches, chairs. Junie and her grandparents lay down on the bamboo mat on the concrete floor together. But Junie lay awake with a tightening feeling in her chest, like a knot that was drawing taut but was also trying to explode too.

The about-to-explode knot said: There’s a world out there trying to lay claim on you. What are you going to do about it?

She waited until she heard her grandparents snoring beside her, then rose from the mat, and scooted quickly on her knees to reach her wooden horse. She knew she didn’t have a lot of time. She propelled herself out the door as quietly as she could. She bounced softly down the steps into the courtyard.

One. Two. Three.

__________________________________

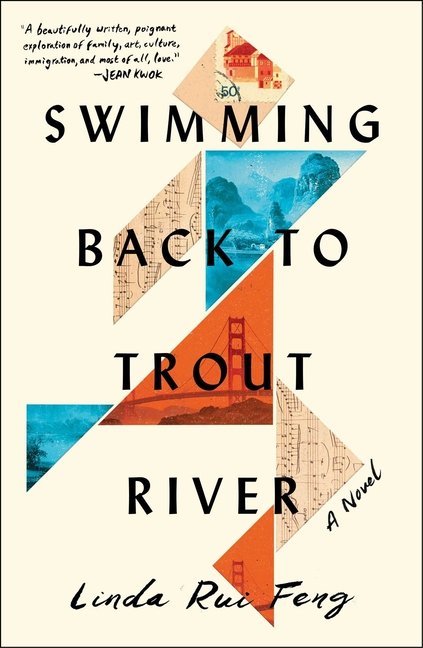

Excerpted from Swimming Back To Trout River by Linda Rui Feng. Excerpted with the permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Linda Rui Feng.