1.

At an abandoned building’s fence, we sat on old ashes and traded banter. we gathered supplies on torn glossy pages between our splayed legs. The pages were brochures from American colleges mailed free of charge upon request. The brochures showed students smiling and holding folders close to their chests or sitting with legs crossed on stone benches, lecture halls with semicircular tiers, beautiful young ladies playing handball on well-manicured turf.

The young ones amongst us wanted to be in those lecture halls overseas. What tongue-wagging, envy-provoking recompense could be greater than getting into an American college when you could hardly make it through secondary school in Kano? We gathered around the brochures with astonished eyes and took rounds sniffing at their glossy pages. We loved the perfumed smell. One of us asked if the air in America smelled like the brochures, as though he was tired of breathing the air here.

We had our doubts about studying in America. First, there was the school certificate exam which we had to pass, and then there was the SAT. What about the money? We could get scholarships if we made high SAT scores, but then we would have to worry about money to register for the exam. Not to mention the ever-elusive American visa if the admission worked out.

“The interviewers always frown their faces and never look at you in the eye. My uncle did a visa interview and came back empty-handed despite days of fasting and prayers for divine intervention,” one of us said.

Our doubts grew bigger, and our dreams of a foreign education became like the ashes we sat on.

2.

Our supplies consisted of flammable things, things collected—used mosquito coil, dead cockroaches, matchsticks, camphor, dried lizard feces. We ground the ingredients into little bits and rolled up fat joints. We smoked with our faces towards the hot, sunny sky, swatting flies with our free hands. Some of us pulled the smoke in gradually; others took long clean drags, drawing the smoke deep into our lungs and holding it in before releasing in little puffs.we huffed and snorted as smoke rose in thick, dark rings, like exhaust fumes from a faulty car. Fresh ash gathered in the dirt.

Then a time came when we competed on how many joints we could shove into the corners of our cracked lips without whooping. Several of us barred our teeth like rabid dogs. Some of us slid our eyeballs into our skulls, showing the white of our eyes.

We also made cocktails of crushed tramadol tablets, codeine cough syrup, and Coca Cola. We drank from plastic bottles and allowed calm to settle on our spirits. Our voices turned hollow and hoarse. We waded slowly through time, the world’s traffic bogged down before our eyes.

Some of us leaned back against the grimy fence and took long pauses between talking.

Some of us danced to the languorous rhythms in our heads, tottering about on uncertain legs.

Some of us dozed off with our backs to the wall. One of us curled up close to the fence, muttering quietly to himself. Another spoke loudly about the abandoned building. He said he would one day buy it and turn it into a big apartment for all of us. The rest of us mocked him for his foolish talk.

The building used to be a textile factory. When the government shut it down, they boarded up the windows, barricaded the doors with iron bars, and padlocked the gates.we could easily have broken in if we wanted to, but we loved gathering at the fence. As much as we were careful not to draw too much attention to ourselves, we wanted the thrill that came with displaying our vices in the open. We loved it when a lone pedestrian eyed us with contempt or a group of women shook their heads in pity as they trudged along the garbage-strewn bush path close to the abandoned building. We loved it when wandering children took one look and ran off like scared mongrels. How our watchers felt about us did not matter.what mattered was that they did not ignore us.

3.

Some of us came from the edges of town. Some of us came from houses made of mud with straw roofing. Several of us were not indigenes of the north but Igbos and Yorubas and Ikwerres. A few of us were sons of army officers, artisans and traders and drivers of three-wheeler taxis. Some of us never knew our fathers or were left under the care of grandparents and uncles. Three of us had no place to call home and home was wherever night fell. A few of us were delinquent teenagers from Christian homes. Some of us had fathers with too many wives to give us any attention.

The youngest of us was sixteen and lived in a gray crumbling bungalow in the city, a house also inhabited by his now wizened and senile grandmother, whose job it was to sit out front and watch the new world go by, understanding little of it.

The oldest of us was a man in his forties with dreams of playing football in Europe even though he walked with a pronounced limp. He lived in the same room apportioned to him by his father when he became old enough to have a room. In that same room he had grown, become a man, and had kids of his own, kids left to grow untended like weeds.

We came together five months ago, the way wild mushrooms gather out of nowhere. One met another. Two met two more. Some idle talk here, some crotch grabbing there. Smokes passed from hand to hand.The group kept getting together and kept taking in new members. No one was turned aside. No one was made to stay, though no one left. At the abandoned building’s fence we became one, yoked in our idleness and anger against the forces bent on crushing us.

We were happy with the universe, as long as we could forget about our problems for a while, smoke, and get syrup-high on the sweet, sweet strawberry taste of codeine. we clung to the thing we knew, the one thing tangible to us—the sweet, painless tenderness of drugs.

Our dreams, when we had any, were fleeting, easily engulfed by our own disbelief. We only began to imagine better times when the CEO showed up.

4.

He came to the abandoned building’s fence one hot afternoon with the oldest of us. His head was a fuddle of bushy hair and whiskers, from which his eyes peered at us. He wore an oversized, snuff-coloured jacket and carried a big leather briefcase covered with faded stickers. They had words on them like “NO BlOOD” and “GOD’S KINGDOM ON EARTH.” Was he a Jehovah’s witness?

We watched as he slowly set down the briefcase and introduced himself as Ben Ten, the CEO of a travel agency he called Boys International Airport. He said he could get us overseas without a visa. Ben Ten’s news put a happy jitter in the oldest but didn’t convince most of us. For we had heard stories of people going to Europe by road, but we had also heard that the journey cost a lot of money.

Ben Ten showed us a map wrinkled and stained with oil. He whipped it out of his briefcase and unfolded it on the ash-covered ground.

“This is how the journey will go. From here we move to Zinder in Niger Republic, then proceed to the desert town of Agadez and then Sabha before we land in Tripoli, the libyan capital. From Tripoli we will take a speedboat across the sea to Europe.Very simple,” he said, tapping his fingers on the map. A few of us moved close and peered straight down, but several of us craned our necks from where we stood.

From the briefcase Ben Ten brought out something else, photographs this time, and passed them around. Pictures of tall buildings flickering with light, arched bridges, narrow streets with cobbled roads, and train stations with high ceilings. Photographs from Europe, he called them. There was no excitement, only curiosity. The photographs looked old and smelled of camphor, not like the sweet smell of the brochures.

We found ourselves wondering what trick was left in his briefcase.we wondered when he was going to get to the point, the point being how much it would cost us for the journey.we wanted the dream to die before it became a dream.

He brought out sheets of paper he called contracts. He read the contract out loud. He said the contract stated we would remit to the last dollar the money committed to our trip. It was in dollars. Thousands of dollars. The contract would give us a minimum of three years to work in order to pay off our debts when we reached Europe.we would not pay anything at the beginning of the trip. We would also work along the way in Sabha and Tripoli.we were to do whatever it took to earn money: manual labor for building projects, dishwashing at cafeterias, bartending at local hotels.

“So we will need no money to go on this trip, right?” one of us asked.

“Yes,” he answered in a voice laced with confidence. “You will work for the money later.we have been doing this for years at Boys International Airport. You can ask around. One hundred percent guarantee to get to Europe.”

That was when we all moved close.

__________________________________

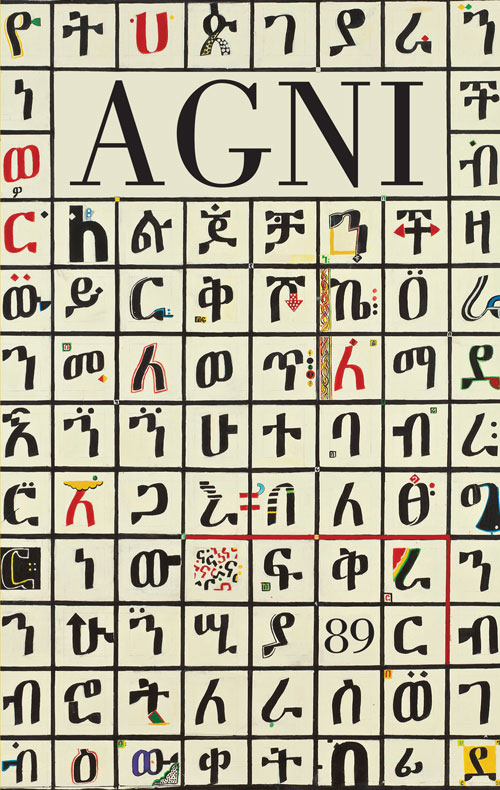

From “Sweet sweet strawberry taste” by Samuel Kóláwólé. First appeared in AGNI 89. Used with permission.