A single white egg rattled around the bottom of a small pot. At the local Miyoshi Mart, a carton of ten cost 198 yen—the cheapest option around here. At a rate of one a day, the whole carton would last for ten days. Cheap, packed with protein, easy to prepare. Just put one in a pot with some water, wait fifteen minutes, and done: a hard-boiled egg.

“Do you know what makes an egg an egg? If you boil it for fifteen minutes, it becomes hard-boiled. That’s the definition of an egg. In cooking, it’s important to know the essence of your ingredients.”

Isogai-san, one of the patients in the nursing home where Riki used to work, never got tired of repeating this refrain. She would sit up straight in her wheelchair, giving off a proud, standoffish vibe, though her pink pajamas were splattered with food stains.

Isogai-san’s name was written in a complicated character that no one could read. Whenever someone pronounced it wrong, she snapped back, correcting them: “It’s Isogai.”

Sometimes she would point to her lapel and say, “It’s Isogai,” even though she wasn’t wearing a nametag and no one had addressed her. And so she became known in the nursing home as the old woman who went around saying, “It’s Isogai,” and “Do you know what makes an egg an egg?,” regardless of whom she was talking to.

But there were no hard-boiled eggs at the nursing home cafeteria, since many of the elderly people there were incapable of peeling an eggshell to begin with. And, besides, hard-boiled eggs could get stuck in their throats. So the only egg dishes the cafeteria served were a sickly sweet dashi-maki egg (always a hit), a dollopy egg-drop soup, or, on rare occasions, a soft-boiled egg.

That’s why Isogai-san’s obsession with hard-boiled eggs was a mystery to everyone. Over time, rumors circulated that she used to work as a cook, which made people more forgiving of her specific brand of dementia. She also developed a reputation for having a spot-on analysis of the nature of an egg.

One day, one of the nursing home staff told the elderly patients about a famous chef she had read about on the internet, who was always going on about the “essence of ingredients.” As a result, patients who had up till then vaguely sympathized with Isogai-san’s “essence of the egg” speeches came to agree with her much more readily. Shortly thereafter, however, Isogai-san caught a cold, developed influenza, and died unexpectedly.

If the nature of a chicken egg is that it becomes hard-boiled after eight minutes, what about the egg inside a woman’s body? If you boiled it, how long would it take to harden? “Oh, Isogai-san! Tell me—what is the essence of a human egg?” Riki called out the familiar name as she stared into the boiling pot.

Riki had worked at the nursing home for almost two and a half years, from age twenty-one to twenty-three. It had taken her that long to save 2,000,000 yen, day by painstaking day. For most people, that might seem like nothing; but for Riki, the only reason she was able to put away even that much was that she’d been living with her parents the whole time.

She was hired at the nursing home, which had recently opened near her parents’ place, shortly after graduating from a junior college in northeastern Hokkaido. Her parents were overjoyed when she was hired, saying it was a good thing, since sooner or later they were bound to end up there anyway. But on her first day at work, Riki glimpsed an old woman playing with a ball of her own feces, and immediately wanted to quit. She couldn’t believe people actually did things like that.

As it turned out, however, it wasn’t the nursing home’s fault that Riki didn’t last long. Wherever she went, it was the same. Even after moving to Tokyo she still couldn’t hold down a job. Sometimes she wondered whether she was the problem, whether she was just too impatient. But eventually she realized what made these jobs so intolerable to her: it was the sense that her fate was already decided, that there was nowhere else to go—while, in reality, she still had no idea who she was, or what she wanted to do with her life.

A while back, a friend of hers from high school had gotten a job at a nail salon. It was then Riki realized that people who were sure of what they wanted to do in life and pursued their goal single-mindedly were stronger and had a much easier time of things. Her friend had gone to a nail-technician school in Tokyo for a year, then started working at a salon managed by the school. Now she was working at the salon’s main branch, in Shibuya. Whenever Riki looked at her friend’s Instagram, she could tell she was thriving. Her boyfriend was a hairdresser who worked in Harajuku. But it wasn’t Shibuya, Harajuku, or the boyfriend that Riki was jealous of, so much as the sense that her friend seemed fulfilled.

She had seen this friend just once since moving to Tokyo, when they met up at a café in Ebisu. This was right around the time when Riki had started working part-time at a company that sorted flyers and other printed material in West Nippori.

Riki felt intimidated at the mere mention of a neighborhood like Ebisu, and her friend showed up that day looking especially elegant, her hair dyed a stylish reddish-brown, dazzling everyone around her. The moment she saw her friend’s elaborate nails, Riki physically and mentally recoiled, scooting back in her chair involuntarily.

She tried to explain away the immense gap that had opened up between her and her friend by the fact that she had never pursued a real career. But when her friend proudly showed off her nails—“Look, I did these myself!”—all she could think was no, it was because she had no talent to speak of that things had turned out this way.

Why was it that things just seemed to be getting worse and worse since she came to Tokyo? There was nothing for her back home in Hokkaido. She’d had a huge fight with her dad right before she left, so she refused to go back, simply as a matter of pride. And, besides, it wasn’t like she had the money to pay for the flight.

She had left home with 2,000,000 yen, but somehow it had all dried up within a span of six months. There was the key deposit for her apartment to pay for, and the rental deposit, then the fridge, microwave, bed, furniture, pots and pans, and tableware. All that on top of her ever-increasing living expenses, and the money just seemed to evaporate. And now she had zero savings.

Her frustration with her job, coupled with the sense that she wasn’t particularly good at anything, left Riki feeling hollow inside, day in and day out. She never knew that being poor could feel this lonely, this suffocating. Just once in her life, she wanted to experience what it felt like to not have to worry about money.

The misery of buying up all the discounted food at the supermarket just before closing, trying to find new ways to cut down on her energy bill, walking instead of taking public transit, buying clothes only at used clothing stores: she wanted out of all of it.

The timer went off on her phone. Exactly eight minutes. Riki drained the boiling water from the pot and added cold water to cool off the freshly boiled egg. She stood at the sink and began to peel off the shell. Sometimes pockets of air would get into the egg while it was cooking, and if you rolled it around a bit, small cracks would appear in the shell, making it easier to peel from the bottom.

She should have told Isogai-san that this was the essence of an egg. But Isogai-san wouldn’t have believed her—even though, if some culinary specialist had said the same thing, she wouldn’t have batted an eye. Riki could just picture her narrowing her eyes in suspicion. This is who I’ve become, thought Riki. A nobody who no one cares about, dismissed even by the likes of Isogai-san.

Riki poured some soy sauce into a dish and dipped her egg into it. Ever since she was a child, she’d always liked eating her hard-boiled eggs with soy sauce, not salt. That’s why she’d hated school field trips: they would only let you bring salt. When she told this story to the first guy she dated after moving to Tokyo, he’d made fun of her for it.

“Soy sauce? On your eggs? Wow, you’re really country.”

He was three years older than Riki. He had a goatee, and a thick northern Kanto accent. He was a bit pretentious. She’d met him while working as a temp at an import shop, though “import shop” made it sound much fancier than what it actually was, which was merely a clothing store. The man said he only worked there because they let him wear a goatee.

You’re one to talk, Riki thought. You’re the one who has an accent. Then, as if he’d read her mind, he started bragging about how the prefecture he was from was technically within the Greater Tokyo Metropolitan Area, so it didn’t count as rural, the way Hokkaido did. He was perceptive only when he sensed that other people might be judging him.

Riki was a late bloomer, and he’d taken her for a fool, lied to her, dated other women behind her back, got what he wanted out of her, and left.

Ever since then, Riki had wondered whether there was really any point to men at all. In her eyes, they were rude, stupid beings who only ever thought about themselves. Throwing their dirty shoes on the floor, never putting them away. Leaving the toilet seat up, not noticing if they left a little pee on the floor, and just stepping in it. Opening other people’s fridges without asking, drinking the bottle of sparkling wine she’d been guarding like a treasure. Falling asleep spread-eagle in the narrow bed and kicking Riki off. And since he believed women were supposed to serve him, he didn’t care if he came inside her. When she told him she was worried about getting pregnant, he laughed, saying if she forced him to marry her because she got pregnant, he’d be the one in trouble.

All the men Riki had met since coming to Tokyo were people she’d never dream of sleeping with even if they were stranded on a desert island. I don’t need a man, I’d rather be alone, she thought—but the reality was that, with her salary, she couldn’t afford to be single.

Riki’s current job was working as a temp in the office of Kitamuki General Hospital. Every day, she sat in that old, dim hospital for nine and a half hours—from eight in the morning until five-thirty, when the office closed. But her monthly pay was only 140,000 yen. Of that, 58,000 went to rent—for a cheap apartment that didn’t get much light—which only left her with 82,000 a month to live on.

Someone else who had the same job but lived at home might be able to afford a coffee at Dean & DeLuca, but as it was, Riki couldn’t even afford a coffee from 7-Eleven. Her contract was supposed to end next year, too, so she’d have to look for a new job after that. She yearned for money and security from the depths of her being.

__________________________________

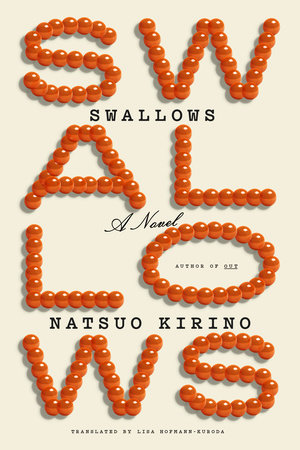

From Swallows by Natsuo Kirino, translated by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda. Used with permission of the publisher, Knopf. Copyright © 2025 by Natsuo Kirino, translation copyright © 2025 translated by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda.