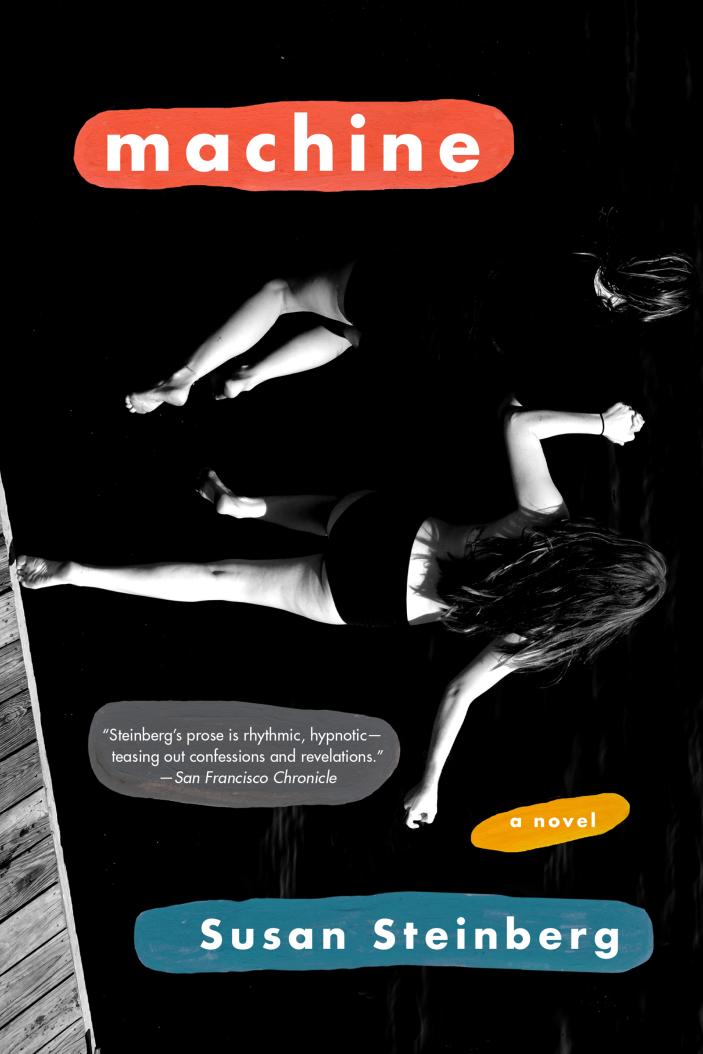

Susan Steinberg on the Value of Writing an Ugly Draft

The Author of Machine in Conversation About Craft with Diane Cook

Halfway through my conversation last week with Susan Steinberg about her new book—her first novel—Machine, I had to backtrack and slip in, “Oh by the way, I loved the book.” She exhaled with relief, and said, “Oh, thank you. You just made my day.”

Of course, I started to sputter effusive praise, so embarrassed that I’d taken for granted that she would know how I felt, how anyone felt, about her work. But I also had to laugh. It was funny to me that I needed to be reminded that we are just writers in need of the same kind of appreciation. I so easily forgot that when faced with Steinberg’s work. Her writing has always seemed to me to be above the fray in some way that, try as I might, I can’t articulate.

It has to do with risk and expectation. How she exercises one and subverts the other. I can never see where she will go, or when or where she’ll double back on herself. She hovers, then bolts when I least expect it. At times reading her work, I feel dizzy. Other times I feel I’ve thrown myself, or been thrown, into a brick wall. The work operates on a level I just gaze at and have feelings about. Like when I go to a museum and look at the the movement of colors on canvas, paper, the wall, whatever has the privilege of attempting to contain it. Her writing makes me see the ways I, regardless of my creativity, play it safe in places I wish I didn’t. By which I mean, Big fan, here.

Nota bene: it feels weird and wonderful to warn this about an experimental literary novel, but, spoilers ahead.

–Diane Cook

*

Diane Cook: I thought a lot about truth when reading Machine. I always do when I read your work because your narrators are always revealing how little truth—and how much subjectivity—there is in any story we try and tell.

Susan Steinberg: Right. I think so.

DC: In the novel, there’s this thru-line about a local girl who drowns. And as I was reading it I thought, “Well, by the end we’ll get to the bottom of this,” because that’s what I’ve come to expect from narrative, and then later I realized that, “Oh no, we won’t!” We won’t get to know what happened to the girl because the narrator doesn’t know. And it’s such a wonderful mindfuck. And made me feel like that’s what storytelling secretly is. Attempting to tell a story that we can never tell because we can never tell the whole story.

SS: I really love that wording. Getting to the bottom. It’s literally what happened, right? I feel like that’s what I wanted to do—take the reader to the bottom of it, you know, to what’s underneath that water to get down all the way to the bottom and, and not come up with the answer of who did this. Which is usually the thing we’re waiting to find out.

But I realized that wasn’t the question I was asking. This isn’t a whodunnit. I was not as interested in who did this, who to point fingers at in this story, but more interested in the narrator’s fixation on who the girl was, what it felt like to be in her position on that night. The narrator never knowing is something I had to kind of contend with because it’s so directly linked to where I, as the writer, am sitting. I chose to limit my knowledge to match hers. I thought it was really important to stay true to the fact that whatever information she got came from outside sources or her own imagination.

DC: Well, there came a point, maybe close to the end, I think, when I thought, “Oh wait, was she there?” And then my brain went in all sorts of ridiculous directions. Like, “Was she there and she’s the one who pushed her?” It became super-narrative, super-whodunnit-y and super-thriller-y, and I had to say, “No, no, no, calm down, Diane.”

SS: I like that, actually. I feel I left enough open—and I don’t know if that was intentional all the way through, for all sorts of possibilities to be true, but now I’m realizing this in talking to you, that there’s something interesting to me for what would normally be the main question that we’re following—”Who did this thing?”—for that to become secondary. I think it’s interesting for that to be a part of the situation, as opposed to the full story.

DC: Yeah. And the most important thing you’ll find out, is who the girl is who is fixated on this. Who the girl is who wants to know. Because to know what happened is instructive to her, to know what happened teaches her more about what it is to be a girl.

SS: Right. Exactly. And also what it is to figure out that you already are that same girl, right? You may feel you’re so different because you live in different parts of this town and you go to different schools and all of this. But at the end of the day when you’re living in a female body and standing on a dock with a bunch of drunk guys and a bunch of girls who don’t like you, maybe things aren’t so different.

I don’t know. I’ve been asked if I was trying to write teenage girls in general, right? That this is sort of the state of teenage girls. And I don’t really think I am so much. Not naming her and not naming the place I think does open it up to thinking, Well this could be any girl. But I also feel like this is a very specific situation and while I think it encompasses what it is to be female, it’s also having a shaky family situation, as well. Anyway, I’m sort of rambling. I don’t know that I ever really understood this book entirely.

DC: I feel like that’s what happens, right? When I write, I feel like, Okay, this is what people need to know to get this book. And then I realize that people are reading all sorts of other things into it and that now I’m the one who doesn’t know anything about what I just wrote.

SS: Yes. That is exactly what I’m going through right now. I’m like, No, wait a minute. Did I write a mystery? I think I wrote a mystery.

DC: Susan, it’s a thriller. It’s a literary thriller.

SS: I’m fine with that. You know, I had no intention of having a girl drown in the book. And then one day writing, I was like, I think maybe I need to go one more with this. I think something more needs to happen. And that was not early on; she was just a character they were mean to for many, many pages.

DC: Wow. Well, I was going to ask you what kind of writer you are. If you are someone who has a plan or if you’re kind of serendipitous.

SS: It’s all serendipitous, all the time. There’s no plan. I don’t have any idea of anything. I don’t go in with ideas really at all. It’s just trying on stuff, having fun, listening to loud music and just, you know, throwing words down and then eventually stories started to take shape and then I kind of follow it and see what might work, try a lot of things on. There’s a lot of trial and error.

I went to art school and studied painting and there’s so much play in art school, at least when I was there, and I assume it’s the same way now. There’s so much just trying things on because everything is new. It’s encouraged to get your hands dirty and try out all these things. And so going from that messiness, where you’re just inventing all the time, which was so exciting, to writing. I just thought, Oh, I can do that here too. I love writing because it’s play.

There are several writers who have told me that they assume that when I sit down to write, that I write a sentence and then I don’t move on until that sentence is perfect. And then I write the next sentence and that’s how I write. And when they find out that that I make the biggest mess you can imagine. I just write and write and it doesn’t always make sense and I go really far out there and then pull back and start to pare it down. I think they’re always disappointed to realize that the stories don’t come out of me that way.

DC: I think that’s awesome to hear. That it’s a total beautiful mess.

SS: And it’s not even a beautiful mess, it’s just super—

DC: It’s ugly. You write ugly and then you sculpt it.

SS: I write ugly, yeah. Yes. All art, for me, starts out ugly and it’s fun. I like making ugly things. I really do. And then you figure it out. You know, you go in and you’re like, well, this word is not going to work. And now you put a new word in and suddenly things look really different and everything starts to take shape. It’s a good time.

DC: It makes sense reading Machine. Every word is right. But there’s also this energy and tumultuous feeling behind everything and underneath everything. It would seem really antithetical to be able to write wild, tumultuous, emotional prose carefully word for word.

SS: What’s going on between me and the screen or the page, because I hand-write too, it really feels that wild. And that messy. And I need that. I couldn’t do it any other way. What would be the point? As painful as the material is, as painful as it is to write a sad scene or to write something that comes from experience or to make up something and even sort of scare yourself because you made up something so sad or so that potentially scary. Even with all of the pain that’s in it, writing is fun. Going into that space of the imagination is fun, and I think it would not be fun to follow a formula. There are places in my life for formula like hair dye, maybe cooking, I don’t know. But in writing, I want to break all of that, or make up the rules because it’s one of the only places we can.

DC: Did you mean to write a novel?

SS: Oh my god. You know, right? I’ve never wanted to write a novel.

DC: Really?

SS: It was an unintentional novel. It was supposed to be a story collection of really super-linked stories. And then in talking over it with my editor, he was like, “Why is this not a novel?” And I was like, “You know, wait, is it a novel?” And then everyone was just like, “We’re sorry, but you’ve written a novel.”

And I was sort of opposed to it, and at the same time really open to it. Like, “I’ll never write a novel!” While at the same time thinking, “Yeah, why isn’t this a novel? Like, why can’t a novel look this way?” So it was sort of an accident, but I was open to it becoming that.

DC: I love it as a novel. The chapters have different distinct forms. There are some that are block paragraphs, and then others look like poems almost, like line by line by line. And then others where it’s like a whole block of semi-coloned pieces put together. But there’s this forward movement and this whole world that’s built with them that makes it very clear they can’t stand alone.

SS: Originally I think they could stand alone. And then as I started thinking of it as one longer piece, I began removing information and that made it so that they really couldn’t stand alone anymore. And that was kind of scary for me.

DC: Yeah, I bet.

SS: Like everything changed, you know? But this thing was just demanding (to be a novel) at this point. You know, I just had to deal with that fact.

DC: I’m curious now: what kind of work your novel does as opposed to it as a bunch of stories? Like when you were saying, “This thing demands to be a novel,” I imagine it wasn’t just that it was demanding that it be a different form, but that it was demanding to do a different kind of work. Do you know what work that is?

SS: I think for me, it was about a sort of commitment to an event that I just couldn’t get out of. It’s like all the questions that get asked in a short story, they don’t all have to get resolved. Right? A short story for me is also an event. A thing happens and it’s often, This is the day that blank happened, right? And that’s how I see a story. And so you can get it into 12 pages, 17 pages, however long it needs to be. In my previous collection, Spectacle, I wrote this story called “Cowboys,” that was very, very hard for me to write. It took everything out of me. And when I finished writing it I felt great. I was like, “I wrote it. That was really hard and that felt like a risk and I’m really glad I wrote it.”

And I don’t even know how much time passed, maybe a week, and I felt like I had to write it again. The emotion was still with me. I had to try it again from another perspective. And so I wrote it twice.

And I think that maybe there’s something about that that’s coming into play with writing a novel. There’s something about a novel that makes you say, I’m going to try this from a different perspective, or through a different form, or from another angle, whatever it is. I think for me some events necessitate a lot more space and time with it than others. Does that resonate with you?

DC: Totally.

SS: I just think some things you have to sit with longer, and that’s just true of everything in our lives.

DC: That makes me think about how the narrator, in the different sections, seems to take on different kinds of perceptions or perspectives. Like in one she seems vulnerable and worn down by the reality of the situation. And in other sections she seems very defiant and very powerful. She takes on these different versions of herself in order to try and figure out the greater world, or the greater world of the story she’s trying to tell, like trying to find a truth. She had to take on all of those perspectives—and so did you as the author—to try and get around this big story in her world.

SS: That’s absolutely it. Like that story, because it doesn’t have an answer for her, because she wasn’t there, I couldn’t wrap it up in a short story. And so I found myself just writing these scenes that were the stories and realizing that this is all just part of one thing. It’s just different ways into the same thing. I think other people have much different and probably easier answers to it. And it’s so personal. It’s like, oh, I could tell the story of this thing, this party, in one story. But to tell the story of the death of somebody for me is going to take many more tries. Right? There’s more to understand.

DC: That’s so interesting. If you’d just written this as a story, it would be a story about not knowing something. Right? It would be about not knowing what happened when this girl died.

SS: Yeah.

DC: But there’s only so much you could excavate in that short story, I don’t care who you are. But then the story as a novel became so much about her and discovering way too much. Do you know what I mean? Like she never knows what happens to the girl, but she comes understand more than. . .more than she ought to know about being a girl and being a human.

SS: Right. Absolutely. I’m glad you said that. I think that’s true. And I think maybe I discovered way too much, too, in pushing that for so many pages.

DC: The ending was perfect and inevitable and I wonder if you always knew it would end that way?

SS: I originally wanted to end the book with a different section, but then it seemed right to end not just with a feeling of frustration but with how complex and human and inevitable that feeling can be.

The process of writing for me is about trying to figure something out. So, no, I didn’t know where this story was going. I never know how anything will end. I just know that, like all things, it has to end at some point, and not all will be resolved. To acknowledge that truth—or what feels like a truth for me—is simultaneously a defeat and a reason to tell the story again.

__________________________________

Susan Steinberg’s Machine is out now from Graywolf Press.

Diane Cook

Diane Cook is the author of the story collection Man V. Nature, and was formerly a producer for the radio show, This American Life. Man V. Nature was a finalist for the Guardian First Book Award, Believer Book Award and the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction. She is the recipient of a 2016 fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. She lives in Brooklyn, NY. Harper will publish her first novel, The New Wilderness, in August 2020.