Survival Dictionary: The Book that Helped Me Define the Terms of My Adoption Memoir

Jan Beatty on the Power of the Epigraph

I was born in Roselia Asylum and Maternity Hospital in the Hill District of Pittsburgh. It was a “home for unwed mothers” where pregnant girls could stay until they had their babies, and then they would leave the babies there. I spent the first year of my life in the Roselia orphanage before I was adopted—as far as I know.

I couldn’t remember my beginnings or much of my childhood. It took years to get a pre-amended birth certificate, and after some detective work, I found that the names on that state-issued document weren’t accurate. I didn’t learn my real name until I was in my thirties. I was driven to write about adoption—but first I needed to work out how to write about that first year and the hazy years that followed, even as they were clouded with the trauma of losing my birthmother, name, and medical history.

Over the years, whenever I tried to write about adoption, I would run into problems more intense than those of not remembering. The attempt to write the details of the orphanage would leave me off balance, sometimes in a dissociative state where I couldn’t locate what was “real” in memory and what was “grounding” in the present tense—what would hold me to planet Earth when I felt like I was disappearing. I decided to give the material a rest until I could continue to work on adoption in therapy and until I was more clear about the writing I wanted to do.

As a young girl, I was always in search of the “real,” since I knew I wasn’t a real, “actual” girl—I was an adoptee who was purchased through social services. One of my aunts gave me a huge dictionary, about twelve inches thick with a red leather cover and silver rivets. It became home base for me, as I kept it in my clothes closet throughout my childhood, reading it for pleasure and knowledge. I also read the encyclopedia, making charts of what I was learning like a little freak mad scientist—such as geographic maps or histories of cities. I spent a lot of time alone. This time turned into poetry and locked diaries under my bed, cliched break-up poems, and other things I shared with no one.

When I finally sat down to collect notes from many years of my journals, I was again stuck. How could I ground myself, keep myself on the earth and not slide into dissociation or a morass of confusion?

I turned again to the dictionary. This time, I was out West, at a writing residency at Brush Creek Ranch about two hours from Laramie, Wyoming. I had dragged a thick, topographical dictionary with me across the country: Home Ground, A Guide to the American Landscape, by Michael Collier, edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney. After meeting Barry Lopez at a writing retreat in Sitka, Alaska years earlier, I had formed a special connection with him, with his love of the natural world—and his presence through this book gave me even more solid ground.

The story of writing my memoir is the story of what the body knows before the conscious mind follows.

The West had long felt like “home” to me: I had traveled across Canada, back and forth, on the VIA Rail, in search of adventure, long before I knew I was half Canadian, long before I started the actual writing of my memoir. I discovered that my birth father was from Winnipeg, Manitoba, and a professional hockey player who won three Stanley cups with the Toronto Maple Leafs.

The story of writing my memoir is the story of what the body knows before the conscious mind follows. I had no idea that I would meet my birth father years after these train trips. I had no idea that years after meeting him, I would start the memoir at Brush Creek Ranch—and that I would again use a dictionary to ground me in some reality of story.

As a way to begin to put pen to paper in Wyoming, I decided to start with a quote from Home Ground by Robert Michael Pyle:

An infant stream is a small, gathering watercourse

at the very upper reaches of a watershed. Such

a stream has only begun its erosive mission of

redistributing the materials of the land downhill.

In heavy rains, the flow in embryonic rivulets

grows from a trickle to a wash.

I was drawn in by the beginning words, “infant stream,” and I chose this quote without further thought. I wasn’t looking for a straight metaphorical thread, but a leaping, instinctual connection.

The “grounding” of the definition gave me an entry into the patterns of my childhood memories. In this section, I began: “The ivy green couch grows rabid in the basement.” Erosion and redistribution in the Robert Michael Pyle quote leaps into details of my life: “With patterns too close together, the 1950s embossed leaves the only witnesses when my sister tells me that our adopted parents are not our friends, they are not to be trusted.” The wash is occurring. And later: “We look nothing alike, her hair burns red and her eyes brown.” When I wrote this, I had none of this connection in mind, but I believe that the images of this definition opened me to receive images of memory, and to lean into the lyrical movement of them.

I regard these quotes, these voices as part of a “family of strangers” who are in dialogue with me in American Bastard. Looking back, it doesn’t seem strange that I, as an adoptee, would need the foundation of these voices to enter a traumatic past and begin to speak.

The connection between “orphan” and “landform” in this quote by Luis Alberto Urrea in Home Ground opened a “new sky” of writing:

Huérfano is Spanish for orphan.

In this case, a perfect description of the landform—a

solitary spire or hill left standing by erosion apart

from kindred landscape features. Also called a

“circumscribed eminence,” a lost mountain or an

island hill, it is kind of an existentialist monument,

an island in the sky.

This quote in particular evoked a sense of loss and the solitary nature of being adopted. Here I talk about that loneliness:

I was born an island in the sky—but I didn’t know

which sky? Why was I in the asylum? What were

the rules here? An infant knows the separation—

no mother and now a crib in a roomful of cribs.

What is at stake in the dream remembered?

What is at stake for the dreamer?

The following epigraph by Terry Tempest Williams from Home Ground perhaps drives a more direct metaphorical connection to its section:

A particularly chaotic type of gaping

river hole, a cauldron, is characterized by “big,

squirrelly, boily water”. . . they sometimes produce

ferocious hydraulics—violent whirlpools, geysers,

and suddenly collapsing haystacks of white water.

I remember writing this section, about my time as a social worker in Moundsville Penitentiary. I wanted an epigraph that portrayed turmoil and instability. In this section, there’s the murder of one inmate by another, and the realization of my drowning in both my own limits as a social worker along with the brutality of the prison system:

It was like a huge wall of water washing over me. . .

One of my clients murdered another one of my clients

in the Old Men’s Colony. No one knew who did it.

After that, when I talked with one of the men, I would

scrutinize his facial movement, his eyes, the way he

was standing—to try and break the code:

was he the killer?

In the revision of American Bastard, I created nine versions over approximately four years of submitting the manuscript. Although the order of sections changed in these revisions, the use of the epigraphs generally remained consistent. The intuitive pairings of the topographical quotes seemed to offer jump-starts and warning bells in their juxtaposition. I discovered that a sense of alienation, disruption, or resistance in the natural world mirrored the content of the memoir.

In the beginning, it was my survival dictionary: huge red leather with rivets, that gave me a pathway to the world as a child. I wouldn’t know for years that this would be my link, the pivot that led me into the stories of my adoption. Later, the topographical dictionary, Home Ground, A Guide to the American Landscape, would be my guide. I followed the trails once again through the definitions I could count on—not the lies on my birth certificate, the fictions that shroud adoptees—but the facts, an entrance to the truth of story.

___________________________________________________________

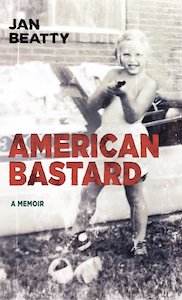

Jan Beatty’s American Bastard: A Memoir is available now via Red Hen Press.

Jan Beatty

Jan Beatty’s sixth book, The Body Wars (2020), was published by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Books include Jackknife: New and Collected Poems (2018 Paterson Prize) named by Sandra Cisneros on Lit Hub as her favorite book of 2019. Awards include the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize, Discovery/The Nation Prize finalist, Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry, $10,000 Artists Grant from the Pittsburgh Foundation, and a $15,000 Creative Achievement Award in Literature from the Heinz Foundation. She directs creative writing and the Madwomen in the Attic Workshops at Carlow University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and is Distinguished Writer in Residence in the MFA program.