Sure, Plot is Good, But Have You Tried Talking About

Story Shape?

Joseph Scapellato's Twist on Story Plotting

I have a problem with plot.

The problem is not with the craft concept that is “plot.” The problem is with me. Whenever I’ve tried to apply “plot” to my writing process, I can’t get it to do what a craft concept should: to permit me to usefully re-see what it is that I’m working on.

To me, “plot” is summary. It’s what you say about a story after a story has happened. It has nothing to do with process and everything to do with product. It’s a static description, not a dynamic enactment.

Whenever I come across kindly writerly advice that encourages me to take certain prescribed steps to construct a good, strong, or well-formed plot, I feel that I’m being asked to come up with a summary of what I’m writing before I’ve written what I’m writing. I feel as if I’m being asked to grow a skeleton in a tank, and when that skeleton has set, to fish it out, pat it dry, and implant it in a floppy boneless body that I have grown in a separate tank.

I’m not anti-plot. To be huffily opposed to “plotted” or “plotty” fiction is just as silly as it is to be huffily opposed to “plotless” fiction. I’m like any other reader: I love it when exciting, surprising, moving, and mysterious things happen in a narrative, and through their happening, immerse me in the wonder-world of the work. But because of the plan-based, outline-oriented connotations that, for me, are attached to notions of plot—connotations that are at odds with my writing process—it’s much more helpful for me to whisper a different word than “plot” to myself when I’m writing: “Shape.”

Any one narrative is going to be made out of many shapes at once, shapes that overlap and intersect and interrupt one another.

I first heard of “shape” during my MFA at New Mexico State University from the brilliant Antonya Nelson, who encountered the term in Jerome Stern’s craft book, Making Shapely Fiction. Nelson, an excellent educator, reshaped Stern’s idea of shape, placing it in the dazzling light of her own laser-sharp insights.

She made the concept hers by adding to it—she talked about the search for what she called “shaping devices”—occasions, situations, or pressures that endow an early draft with conflict-making boundaries—and “the clock”—is there a tension-building “time limit” in your draft, one that is perhaps the product of its shaping devices?

Here is my own understanding of shape: it is a structural container for a narrative. The most important practical quality of a shape—its most useful feature for a writer—is that it suggests “natural” beginnings, middles, and endings. Any one narrative is going to be made out of many shapes at once, shapes that overlap and intersect and interrupt one another.

Shape is a way of composing and revising a narrative, but it’s also a way of interpreting a narrative; not every reader or writer is going to see the same shapes in the same work, or even the same features of the same shape.

One shape that comes to mind: the journey. A character is called to action, undergoes trials, and returns with something to show for it. That’s one interpretation of the beginning, middle, and ending positions “natural” to the journey shape. Here’s a sampling of some other recognizable shapes: a romantic relationship, a friendship, a life, a quarter-life crisis, a midlife crisis, a trip, a case, a project, a puzzle, a game, a ceremony, a competition, a war, a period of imprisonment, a period of employment, an illness, an emotional state, a season, a sports season, a month, a week, a day, an hour. This conception of shape is intentionally broad, forgiving, and open-bordered.

Most of JK Rowling’s Harry Potter novels are in the shape of an academic year; they begin shortly before the school year begins, and end shortly after the school year ends. Toni Morrison’s Beloved is in the shape of a ghost’s acts of haunting, from lights and sounds and shakings in a house, to a physical manifestation/return, to a departure. Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation is in the shape of the narrator’s year of trying to sleep as much as possible with the help of drugs. Laura van den Berg’s The Third Hotel is in the shape of the main character’s trip to a film festival in Cuba, and inside of that shape—closely curving to it—is the shape of her relationship to her recently deceased husband, which continues when she sees him, seemingly alive, in Cuba.

These shape summaries are similar to plot summaries in that they are highly subjective and do not do the novels that they summarize any justice whatsoever. What they do, instead, is bring a readily applicable writing strategy to the surface, a way of re-seeing that you can turn towards your own work.

If you look for shapes in your fiction, and see some, you can use them to help you figure out where to go next. You can also use them to help you make an early-draft beginning, middle, or ending harmonize, structurally, with a later-draft beginning, middle, or ending. You can move into the “natural” beginnings, middles, and endings suggested by shape, or you can subvert or challenge those “natural” positions.

These ideas have been invaluable to me. In my novel, The Made-Up Man, all of the present action takes place over three days, in Prague. But early drafts of the novel—years of early drafts of the novel—began with the main character’s day trip out of Prague, to visit the Sedlec Ossuary in Kutná Hora. Although this opening was in some ways thematically appropriate, I had a bad feeling that it wasn’t doing what it needed to be doing. It was disorienting. It lacked momentum.

What shapes are you ignoring—because they don’t match your initial idea for the work, or because they’d be difficult to implement?

Nevertheless, for a very long time, I pretended that it worked.

Then, one day, while revising, I said to myself: “Shape.” I thought about where the middle and the end of the novel were headed, and I realized that those parts didn’t match the wonky beginning; instead, the middle and the end were setting into the shape of the narrator’s trip to Prague. By this logic, it made more sense to start the novel not with the narrator taking a trip out of Prague, but to start with his arrival in Prague. I made this change. The improvement was immediate—more momentum and life, more clarity, and somehow, more mystery, too.

I don’t know why it took me so long to revise towards a narrative structure that now seems extremely obvious. I do know, however, that I never would have seen it as a possibility if I’d been saying: “Plot.”

It’s possible to productively resist the “natural” positions of shapes—you can seek generative narrative freshness in the act of working against discovered structures. In earlier drafts of The Made-Up Man, it seemed that the “natural” place to end the novel was at the end of narrator’s stay in Prague—when he physically exits the city. This ending, however, kept coming out in an unsatisfying way. It was abrupt.

At some point, I wrote past it; after many, many drafts, I tried to make the new ending reflect a more metaphorical departure from Prague, from everything that it comes to represent for the narrator. The idea of shape helped me to see that this approach was permissible.

Here are the shape-centered questions that I asked myself whenever I needed to rethink my draft’s half-constructed, half-demolished structures:

1. What are some shapes that you see in your draft? (What parts of shapes are already there? What whole shapes are already there?)

2. What are some possible shapes that your draft is ripe for? (What shapes could you organically add, pursue, or lead with?)

3. What shapes are you perhaps resisting? (What shapes are you ignoring—because they don’t match your initial idea for the work, or because they’d be difficult to implement?)

4. What are the “natural” beginnings, middles, and endings suggested by these shapes? (What exciting, surprising, or mysterious complications can you put into these positions? How can you subvert the expectations of these positions?)

As writers, we’re not under a binding contract to adhere to any one set of craft vocabularies. The terms that work for one writer (or for one project) aren’t guaranteed to work for anyone (or anything) else. When I don’t know what to do or where to go, when the terms that I’ve been using prove useless, I try to remember that my only obligation is to find a way to hold onto whatever it is that’s feeling wondrously alive—what’s emergent, what’s real—and to be led by it, all the way to the end.

__________________________________

Joseph Scapellato’s novel The Made-Up Man is available now.

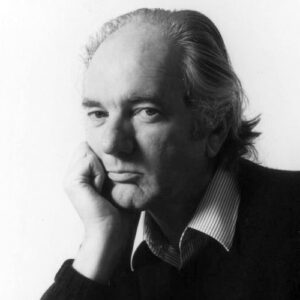

Joseph Scapellato

Joseph Scapellato is the author of the novel The Made-Up Man (2019) and the story collection Big Lonesome (2017). He was born in the suburbs of Chicago and earned his MFA in Fiction at New Mexico State University. Joseph teaches in the creative writing program at Bucknell University and lives in Lewisburg, PA, with his wife, daughter, and dog.