It was summertime in Sydney. At about half-past two on a certain Wednesday afternoon Claire Edwards was leaning on the filing cabinet in the office of J. W. Baker’s wholesale fashion house. She smiled into the telephone receiver.

‘Oh, that’s fine. I’ll meet you at quarter to six, then, outside the Martinique. Try not to be late,’ she cautioned as she had done without success many times before. Her smile deepened to one of indulgent disbelief at Annette’s vehement promises of punctuality. ‘I believe you. Bye-bye.’

Miss Frazer had come through the door leading from the factory a few seconds before Claire replaced the receiver, and she stood watching the girl, her clear grey eyes noting every fleeting change of expression.

‘Annette?’ she asked, glancing at the phone. ‘What kind of job has she found this time?’

‘She’s in a fur shop—a furrier’s in Double Bay,’ Claire answered. ‘I’m meeting her after work to hear how she gets on today. I hope she likes it.’

Miss Frazer looked at her watch and sat down at one of the three empty desks in the small office. Paddy, the accountant, was at the bank; Mr Baker was out for the afternoon, she knew. She felt like having a talk and a cigarette.

Claire recognised the signs with feelings of interest and impatience: interest, because in some of her mind she enjoyed these lengthy, emotional chats with Miss Frazer; impatience, because in her fanatical zeal for her job she resented any hindrance to her plans for the afternoon.

‘Would you just have a look to make sure the girls are working and bring my bag back when you come, please, dear?’ Miss Frazer smiled.

Claire’s impatience melted and her heart warmed as it always did under the older woman’s direct influence. No one had ever made her feel so appreciated, so efficient, so necessary. ‘Of course.’ She smiled back, and went through the stockroom to the factory with a swift, haughty, high-heeled walk.

Forty girls were bending over their machines more or less industriously; a few stood at the ironing boards ostensibly waiting their turn to press some small piece of material. Several canvas stands clad in half-finished dresses blocked the narrow passageways between the machines, cutting tables and delivery racks. At the far end of the factory the designers were discussing a difficult new pattern.

Claire’s eyes swept over the room, her face stern and, she hoped, reproving. She found Miss Frazer’s bag under a pile of soft pink organza and started back for the office. The noise of the machines and the blaring wireless was muffled as the door closed behind her.

‘All right?’ Miss Frazer raised her thin eyebrows.

‘Working away,’ Claire said, ignoring the idlers by the ironing boards.

Miss Frazer, who was really Mrs Douglas Preston, lit a cigarette and leaned back in her chair. Apart from her fine skin and large, clear grey eyes she had nothing much, as far as appearance went, on the credit side, except that she dressed well. That magnetism, that charm couldn’t come under the heading of appearance, and yet they were so real as to be almost visible.

Everyone knew that hers was an ideal marriage; it had lasted for fourteen years, so far, in a state of extreme harmony. Miss Frazer was naturally reluctant to discuss so intimate a subject as her own married life with many people, but she did mention it to those who were unhappy and came to her with troubles.

‘It’s the least I can do,’ she thought, ‘to give the poor things a little glimpse of what life can mean when you are loving and beloved.’

And so, while she didn’t talk about her happiness to many people, most knew about it. It was the kind of news that seemed to circulate. In any case it somehow shone from her.

‘Annette’s a funny girl,’ she began now, her eyes fixed on Claire’s. ‘What is she again? Hungarian or Polish?’

One must start a conversation in some way and, although Miss Frazer’s interest lay more in the rich deep seams of pain, problem, and frustration than in the thin surface soil of mere chatter, she understood the art of mining for such drifts. She’d had practice, of course.

Claire, aware of herself, aware of Miss Frazer and half suspicious of her motives, always responded to her cue and squashed her doubts. It was a stylised game, stimulating and satisfactory, like chess.

‘No, she’s Estonian,’ she said. ‘Her mother and father came out here when she was a baby. She doesn’t even know the language.’

‘They’re beautiful stockings you have on today, Claire,’ Miss Frazer said as she blew a cloud of smoke into the air. ‘Really lovely.’

Claire glowed with pleasure as she glanced down at her long legs.

‘Is she a naturalised Australian?’ Miss Frazer asked, frowning for a moment at the chipped polish on her thumbnail.

‘No, I don’t think she’s ever bothered about it,’ said Claire. ‘It costs five pounds or something like that, and you know Annette, she never has any money.’

‘If she would stick to one job for a while, she might have,’ Miss Frazer said rather tartly.

Annette was a pretty blonde girl whose mother had led her to believe that her looks alone would provide all the necessities and luxuries of life. And, although this belief in the magical properties of a good figure had not so far been justified, Annette’s indolent and optimistic disposition made her content to wait for the inevitable. Miss Frazer knew her only through Claire, but she felt slighted by the girl’s self-sufficiency.

‘How does she get enough money to go out with you?’ she asked, feeling that, since it was rather a boring afternoon on the whole, she might as well get to the bottom of Annette.

‘Her brother runs a taxi. It was left to him and Annette and her mother when her father died. She gets a share of the takings now and then, and I think they own the house they live in.’

This fact-finding mood of Miss Frazer’s always seemed the least attractive side of her to Claire. ‘She wants to know everything about everyone I know, and everything I think,’ she thought. Claire refused to acknowledge that censorship of principles, opinions, and friends was the price she had to pay for the sympathy and understanding that had become necessary to her.

Miss Frazer ground the butt of her cigarette into the ashtray and stood up. She smoothed the skirt of her well-cut coffee-coloured dress and picked up her bag.

‘Well, she’s a silly little girl, Claire. She has some mistaken ideas about life, I think. Although she’s been here all her life, it’s not the same as having British blood.’ Miss Frazer gazed into Claire’s eyes, ‘I only hope she doesn’t pass any of them on to you, dear.’

It was impossible not to feel flattered that Miss Frazer cared about the ideas one had. Claire smiled a reassuring Anglo-Saxon smile.

Rubbing her hands together rather impatiently Miss Frazer said, ‘Now I must make a few calls before Paddy comes back from the bank.’

Claire returned to the factory at once, revived and relieved by the noise, warmed by Miss Frazer’s goodwill, eager to dispatch her work with even greater efficiency and speed than usual.

A Bing Crosby record was playing. The machinists joined in, concentrating more on the reproduction of Crosby-like voices than on their sewing, Claire thought. But it was a hot afternoon. No one could really blame them. The factory needed air-conditioning to make production rise.

As she bent over the thick invoice book she heard the jukebox in the café downstairs begin to play. The competition spurred the girls to greater efforts and their voices rang out above the whirr of the machines.

Claire worked steadily for the rest of the afternoon, invoicing, answering the phone, interviewing travellers, delighting in the knowledge that she had become a vital part of the firm. ‘I hope Annette has something she likes as well as this,’ she thought as she ran downstairs just before five-thirty, clinking the keys of the business possessively.

Annette arrived at the Martinique promptly at a quarter to six. ‘Hello, honey,’ she smiled widely at her friend, and groaned as they went into the bare but atmospheric coffee lounge. ‘Wait till I tell you.’

By mutual consent they saved the news for some minutes. Removing their short white gloves with casual deliberation, they studied the menu with the air of detachment they had practised since they were sixteen.

Their order given, they gazed at the other coffee drinkers with bored, haughty faces. Their own reflections were scrutinised even more carefully in a full-length mirror conveniently close to their table.

It gave back Annette’s yellow hair, smooth, tanned skin and wide mouth: a very attractive face. And Claire saw with satisfaction her own beautifully simple black-and-white sleeveless dress, crisp and elegant over a taffeta petticoat. They smiled at one another affectionately.

‘Now tell me!’ Claire cried, impatient to know Annette’s decision. She had always felt that Annette needed guidance and, being blessed herself with sense and intelligence, it was her duty to help Annette choose the right path in life. Theirs had been an ideal friendship for this reason. Claire organised everything, including Annette, and this suited them both.

Annette said, ‘It’s no good, honey. I just sat out in the shop all day and I was bored stiff. I didn’t like the other girl, and the boss expects you to look busy even when there’s nothing to do.’

‘Oh, Annette, you’re always getting bored stiff,’ Claire wailed. ‘You might like it better tomorrow.’

Annette looked stubborn. ‘Well,’ she said, choosing her words carefully, ‘I might not go tomorrow.’

They were both silent when the waitress brought their order, then Annette went on rather defiantly, ‘Otto and some of the boys rang me this afternoon. They’re up on leave from the Snowy River and they want me to go round with them while they’re here in Sydney for a few days.’

‘Who’s Otto?’

‘He’s a Lithuanian. He works in a migrant camp. Remember he came to a party at our place last time he was on leave?’

‘No, I don’t remember.’

She had never seen Annette’s mother or her home or been to one of the many parties that enlivened Annette’s existence. They seemed to be very gay affairs, starting round eleven and going on until breakfast time, when the family and the guests would usually go to bed for the day.

Annette had always told Claire that she didn’t think she and her mother would like one another, and for that reason she kept them apart. Claire didn’t mind about not seeing Annette’s mother, but she was sorry that the ban placed parties out of bounds, too.

After one of these sprees Annette would say, ‘You wouldn’t like it, though. All foreigners.’ Her eyes would shine with remembered fun, and Claire would feel, but not say, that there was nothing that she would like better than a party, ‘all foreigners’.

Annette’s eyes were shining now, and she smiled, showing her beautifully even white teeth. ‘I was sure I’d told you about Otto. He was the funny little one who kept saying he loved me.’

Remembering that she was in disgrace for threatening to leave her job, and had no right to be smiling, Annette’s high spirits subsided and she concentrated on her meal.

Claire’s irritation collapsed in laughter. ‘This is good! Cheer up, honey, and enjoy your dinner,’ she said. ‘You win! But you are a problem. What are you going to do when Otto and his friends go back to work?’

Annette raised her eyebrows and looked indifferent. ‘Don’t know. I might get another job, or I might just go swimming instead of sitting inside a dreary old fur shop.’

‘How much money have you?’ Claire demanded.

‘About ten shillings.’

‘And how much were you to get at this place in Double Bay?’

‘About twelve pounds a week.’

Claire asked the waitress for the check. She and Annette wiped their buttery fingers, inspected and repaired their lipstick, and put on their white gloves.

‘Where to now?’ each asked as they stepped out into the dark, warm night.

‘Like to go to a show?’ Claire said, waving vaguely at the neon signs which flashed restlessly down the length of the street.

Annette’s face was rueful. ‘Too broke, honey. How about catching a ferry across to Manly and back? You can give me a good lecture and tell me what dear Miss Frazer has been doing today.’

The little thrust at ‘dear Miss Frazer’ aroused mixed feelings of envy, pity, and annoyance in Claire. Annette laughed at the expression on her face, so that several people passing by looked at them. Claire laughed too, catching Annette’s arm and saying, ‘Come on, we can just catch this tram down to the Quay.’

‘Are my seams straight?’ Annette cried anxiously.

Claire dropped a step or two behind her. ‘Fine! Now run for the stop.’

They parted at the station later that night on a wave of affection. All was harmony; all was agreed. Annette was going to give work another trial, and report to Claire the following night before going home to see Otto and the boys.

Claire, for her part, saw that Miss Frazer was a ‘bit of a menace’ as Annette put it, and resolved to withstand her powerful charms. Their thoughts, as they were borne home in opposite directions, turned on one another and their respective tasks for the next day. ‘What a blessing we each speak the same language,’ they thought. ‘How lucky to get good advice from the right person at the right time.’

*

Mr Baker didn’t leave the office all morning, but kept Miss Frazer engaged discussing the new styles for the winter season. He was a fussy little man, by no means unaware of the incandescent sympathy and affection in Mrs Douglas Preston’s eyes. He needed his share of the world’s understanding as much as anyone, and counted himself lucky in having one of its natural sources in his employ.

After lunch, having unburdened his soul for several hours regarding the business, his family, and his feelings about them, Mr Baker was able to go out into the city, appreciated, vigorous, and refreshed.

Miss Frazer came into the factory when he left and sat down beside Claire, who looked up from the invoice book. The noise of the machines and the wireless made conversation as private as in a confessional chamber.

‘Hello, dear,’ Miss Frazer sighed. ‘What a morning I’ve had. I thought he’d never go out.’

Claire cleared her throat sympathetically and returned to her book.

‘What’s the matter, Claire? You don’t seem like yourself.’ Her voice had a slight edge.

This was an old scene, too, and had its own rigid pattern. Claire determined to break it for once and, she thought, for the last time.

‘I’m perfectly all right, Miss Frazer, thanks,’ she said, flipping through the prices book.

There was no reply and Claire was mildly horrified by her own presumption in failing to respond to the proffered invitation. As she worked through her list of jobs her heart thumped apprehensively. What would happen next?

After ten minutes of extreme silence, Miss Frazer, not looking at her, said in stifled tones, ‘Come through to the office with me please, Claire.’

Picking up her bag she went from the room, her head high, her eyes on the floor.

Claire sighed and put down her pen. She looked around the factory for inspiration to help her through the crisis. One of the machinists, Eloise, caught her eye, her expression inscrutable. Claire looked away and went through to the office. ‘Paddy would be at the bank again,’ she thought. ‘Oh dear.’

Miss Frazer sat facing the door, waiting for her with all the weapons of her powerful personality ready for use. And she was hurt: anyone could see it. Very hurt.

‘Now tell me truly, dear. What is the matter with you today?’

Claire’s head swam in nightmarish fashion. ‘Really, Miss Frazer, nothing’s wrong!’ she said, trying to sound convincing, for as soon as the words formed, she doubted their fundamental truth. Wasn’t life really hollow and pointless? How could life be all right if one was not happy, and who in the world was happy but Miss Frazer and her husband?

‘Did Annette upset you last night?’ Miss Frazer asked, giving the impression that she would willingly ask every question in the universe if only she might be allowed to solve this problem and remedy its cause.

Claire was momentarily surprised back to reality. ‘Annette?’ she repeated. ‘Oh, no!’

‘And yet,’ said Miss Frazer, ‘your face is strained. There are circles under your eyes, Claire. And you haven’t been very nice to me today, you know, though I’m trying to help you, dear.’

‘How kind she is,’ thought Claire, wanting to cry. ‘How kind!’

‘I know that, Miss Frazer,’ she said. ‘Really, I do. But nothing’s the matter.’

Her interlocutor bore the anticlimax gracefully. ‘Then if that’s true, dear, I’m glad. Just remember that I’m here if you ever need me.’ She was silent, watching Claire’s averted head, then she smiled gently. ‘Look at me, Claire!’

Claire turned reluctantly, and Miss Frazer gazed at her tearful eyes with an involuntary expression of sheer curiosity.

Endeavouring to regain her self-possession, Claire said, ‘I’m seeing Annette tonight for a few minutes to hear if she’s staying at her job.’

But Miss Frazer’s interest had reached its maximum and was declining; her tone was brisk. ‘Are you, dear? I don’t think that girl has a good effect on you. Now,’ she added, ‘we’d better do some work before Mr B. comes back.’ She turned to the phone and the session was over.

It was hot again, about ninety degrees. Claire felt exhausted. The noise in the factory intensified the heat. She wrote mechanically for the rest of the afternoon, the pen slipping now and then in her hand.

She waited at the Martinique from twenty to six until half-past. Annette was not coming. Claire went home feeling hungry and depressed. ‘Too bad of Annette not to ring to say she couldn’t make it,’ she thought indignantly at intervals until she went to bed.

*

On Friday, Claire woke with a sore throat and a temperature, and when her mother insisted on phoning the office she didn’t feel well enough to protest.

Her room was quiet and she slept for an hour or so, then after having tablets and a hot drink she lay back on the pillows, her head turned to the window. She had a view of tall gum trees on some uncleared land, and down below the slope was the harbour shining in the sun.

The only sounds were the postman’s whistle and an occasional car. Inside and outside her room all was quiet, all was warmth and light.

The noise of the telephone in the hall seemed a violation of the morning. Claire pulled a pillow over her exposed ear and continued to study the deep blue sky, but her contemplation was disturbed again.

‘It’s Annette,’ her mother said. ‘Will I bring the phone through for you, or will I tell her you’ll ring tomorrow?’

‘Would you bring it in, please?’ Claire asked, shivering a little as she sat up.

‘Hello, Annette?’

‘It isn’t Annette,’ the answer came. ‘It’s her cousin Effie. Annette’s here but she doesn’t want to speak to you.’

Claire felt a quickening of her senses, a current of alarm. ‘Why not? Because of last night?’ she asked.

Effie sounded excited. ‘Annette was very sorry about letting you down last night and she rang you at work this morning to say so…’

‘Well?’ Claire’s throat was dry.

‘Well,’ Effie said emphatically, ‘she knows now that you’ve been discussing her with Miss Frazer. You haven’t been saying anything good, either, because Miss Frazer gave her a great lecture this morning. Annette’s very upset.’

‘Oh,’ said Claire in an expressionless voice.

‘And I told her she shouldn’t bother any more with a friend who treats her like that,’ Effie said. ‘She quite agrees. She doesn’t want to meet you ever again.’

‘I see,’ Claire said flatly.

Effie, prepared for battle, was nonplussed by the enemy’s surrender, but after hesitating she shouted, ‘Goodbye, then!’ and hung up.

Don’t think about the future. Don’t be lonely or frightened or sorrowful, just yet. Look at the gum trees and the sky. Look at the pattern on the ceiling. Look at the flowers on the dressing table. Don’t think about Annette.

The phone rang again.

‘Hello?’

‘Hello, dear,’ Miss Frazer said. ‘I’ve been trying to get you for about ten minutes, but your line’s been engaged. How are you feeling now?’

‘Not very well.’

‘Oh!’ There was a pause. ‘I won’t keep you long. I just wanted you to know that I’ve had a long talk with Annette. She told me about forgetting to keep her appointment with you last night and I was really annoyed with her. I told her that she didn’t deserve a friend like you.’ She stopped again. ‘Are you there, dear?’

‘Yes, Miss Frazer.’

Her voice grew higher and quicker. ‘And I took the opportunity of telling her that, since she was lucky enough to be living in this country, the least she could do was to become naturalised and take a job like everyone else. Don’t you think I was right, Claire?’

‘Doubting yourself?’ Claire wondered. ‘I’ve just had a call from Annette,’ she said.

The briefest hesitation. ‘Did she apologise to you, Claire?’

‘No.’

‘I see.’ Miss Frazer’s voice took on its special note of intimacy. ‘She really wasn’t good enough for you, dear. I think she has been a bad influence on you.’

‘Do you, Miss Frazer?’

‘You’re not crying, are you, Claire?’

‘No, Miss Frazer.’ An odd smile tugged at Claire’s mouth. ‘No, I’m not crying.’

‘I’m glad. I won’t talk any more now, dear, but we’ll have a long chat when you come in to work. I promise you, dear, you’re better off without a friend like that.’

‘Perhaps you’re right.’ How easily she said it.

‘Then goodbye, darling,’ Miss Frazer crooned on her most maternal note.

Claire’s eyes were sombre.

‘I hope you’re a lot better tomorrow.’

‘I expect I’ll feel fine. ‘Bye.’

Turning to the window Claire saw that the tall, spare gum trees had begun to wave their branches in the warm breeze. The sky was endlessly blue.

A kookaburra’s laugh rang out. It lasted for a long time.

‘It’s going to rain,’ she thought.

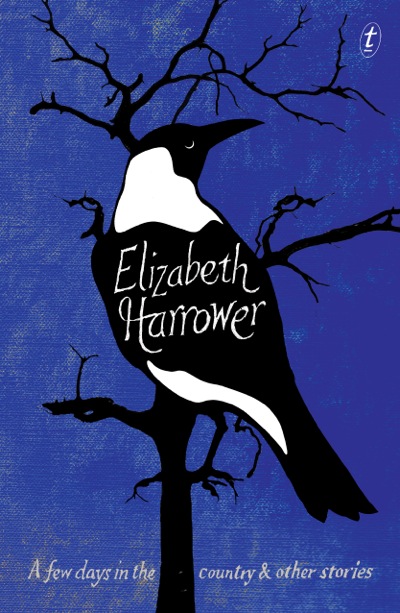

From ‘SUMMERTIME’ from A FEW DAYS IN THE COUNTRY: AND OTHER STORIES. Used with permission of The Text Publishing Company. Copyright © 2015 by Elizabeth Harrower.