Summers on the Forest: What It’s Like Training to Fight Wildfires

Kelly Ramsey Recounts Her Early Days with the US Forest Service

“Family,” in my experience, was an unreliable concept, an abstract that never quite cohered before dissolving entirely.

Thirty years later, I sat on the porch of a farmhouse in Fentress, Texas. The phone rang, and I looked at the screen, shocked by the name that appeared there. I could count the times he’d called in three decades on one hand, and still I could guess what this was about. I picked up anyway.

“Dad?”

“Hello, little daughter of mine.”

Tripping over my words, I split the difference between asking him how he was, and where.

My dad was homeless. A severe alcoholic, he drank until liquor was the lone star by which he navigated a world he was darkening himself, glass by glass. He had abruptly left my stepmom and their four kids years before. He drank until he could no longer work, then stayed with friends or girlfriends until they kicked him out. He lived with each of my sisters, who eventually were forced to boot him too. Finally, he slept in his truck, until he crashed into a concrete post and couldn’t afford to get the vehicle out of impound.

Now he was just . . . out there. Like an animal in the cold. He sometimes scored a bed in a shelter, sometimes slept on the street. This was a shelter phase, I thought; you had to be sober to get in, and he sounded lucid.

“Madeleine got me a few shirts,” he was saying. My youngest sister, who often took care of him. “Courtney brought me some underwear and socks. It’s hard when all you got is a backpack.”

My nostrils burned. I blinked back tears. I’d been right; he was asking for money. But I no longer cared.

“What do you need?”

He said, matter-of-factly, that he could use a second pair of pants. That way he’d have something to wear while he washed his first pair at the Laundromat. I tried to imagine a life reduced to two pants, dirty and clean. I tried not to wonder how filthy he was.

I told him I’d send money to Courtney, who would get him the cash. He might spend it on whiskey, I knew that. But I was helping him for my own sake. To comfort myself.

“Thank you, my beautiful daughter,” he said warmly.

My ear held and squeezed the sound of that “you,” spoken as only a man from Kentucky could, like the tree that grows wild along river banks, the species they say cures cancer. Yew. He could still make me feel like the only “you” on earth.

But the image woke me at night: My dad curling up to sleep on a sidewalk in the cruel midwestern winter. His body a lump under a blanket, under a tarp—like someone who might have already died.

It was almost too much to bear. So I didn’t; I pushed my feelings down. Or rather, I sweated them out. I began to take long hikes, usually alone. I backpacked into the Grand Canyon, scaled a fourteen-thousand-foot peak in Colorado, jumped from a high bridge into a Guatemala river. I trudged desert dunes, crossed islands, and scaled volcanoes. With relief, I learned that a certain level of physical exertion—call it “exhaustion”—would silence sadness. About ten miles in, there lay a quiet place, a wide-open pasture in the mind. I pushed myself there again and again.

Despite all this effort, I sensed grief, like a relentless predator, gaining on me. So I ran.

Less than a year after hanging up the phone on that Texas porch, I ended a relationship, shoved my things into a storage unit, and drove to California. There, I found that the outdoors could be more than an escape; you could make a life out there, even a career. The volunteer position I took on a trail crew soon became a paying job as a wilderness ranger. Happy Camp and the U.S. Forest Service took me in.

All season I begged to be taken on a fire. But it was a slow summer, with few fires in Northern California; the local crew went to Canada, and I was devastated not to be picked up as a fill-in.

Over the next two years with the Klamath National Forest, I learned the difference between a ponderosa and a Jeffrey pine (it’s in the bark texture—“Gentle Jeffrey, Prickly Ponderosa”). I could distinguish the hoot of the aggressive barred owl from that of the reclusive northern spotted owl. I could navigate the Marble Mountain Wilderness by feel, buck a log with a crosscut saw, replace a trail sign, dig a new trail, or rescue a lost hiker. I could read water well enough to float Class IV rapids in an inflatable kayak. I knew the cry of the red-tailed hawk, the secret swimming holes on every creek, and where to pick blackberries when they ripened in July.

My second summer on the Forest, I lived in a government barracks with female firefighters, ladies who could do hundreds of push-ups and run a six-minute mile. They came home from assignments reeking of woodsmoke, faces smudged with ash. Though they claimed to be exhausted, they were lit up, as if brought to life by fire. I had dated a firefighter my first summer out there, and I’d admired his chiseled physique, but seeing the women was different.

As we held pull-up contests in the kitchen doorway, and as I watched them come and go, muscular and unapologetic in heavy leather fire boots, I was smitten with a new vision of what a woman could be. In a word: strong.

That summer I got Red Carded, or qualified as a wildland firefighter. Doing so required online courses in firefighting methods and successful completion of the Pack Test, a three-mile walk wearing a forty-five-pound weight vest to be finished in under forty-five minutes. Since I’d been backpacking all summer for work, a six-foot cross-cut saw (like the old, two-handled lumberjack saw) balanced on one shoulder, I blitzed through the Pack Test, hardly breaking a sweat.

All season I begged to be taken on a fire. But it was a slow summer, with few fires in Northern California; the local crew went to Canada, and I was devastated not to be picked up as a fill-in. Finally, in late August, an engine needed an extra body to tag along on a lightning strike, and I hopped in a truck with two guys I’d never met.

We hiked to the top of a peak called Tom Martin. It was less hike, more hand-and-foot scramble over bear-sized rocks. We carried our line gear (firefighters’ version of a backpack) and a hand tool, plus bladder bags, which are yellow satchels holding five gallons of water. You attach a brass hand pump to the bladder for spraying out hot spots on a fire. All told, we carried seventy pounds apiece. Weighed down, the bladder sloshing, the climb was painfully hard, but I grinned the whole way up the hill. Doing something that difficult felt like a high.

At the top, the “fire” was a letdown. Lightning had struck a single ponderosa pine, blackening its trunk. By the time we arrived, the day after a lookout spied the inky smudge of a new start on the horizon, somebody had already cut the tree down. Now it lay on its side, a corpse smoldering in a pale cloud of smoke, hints of red flickering poker-hot under the armored plates of bark.

We grabbed our tools and made quick work of scraping away the burning bark, cooling the log with water as we did so. At six thousand feet, the peak’s vantage point offered panoramic views in three directions: the green swale of Seiad Valley to our west, the pink crests of the Red Buttes Wilderness to the north, and to our right, the hills of Oak Knoll, the eastern district of the forest, where timber gave way to scrubby chaparral.

“Whoa,” said Dakota, a bearded first-year firefighter on the engine. He was gazing at the horizon.

I stood and looked. “Whoa.”

While we’d had our heads down working, something had happened to the east. I’d overheard the noise on the radio, an evolving incident: the Lime Fire. Through the early morning hours, the fire had lain quietly in the shade. Now it awakened, climbing a brush-packed slope on the far side of the valley, flames licking upward. The Lime began to put up a column, meaning that all the threads and tendrils and wisps of smoke rising from every burning bush and tree and blade of grass braided together, billowing and twisting, climbing the sky, forming a pillar of smoke that tied the earth to the stratosphere.

If you’ve ever seen a photo of the mushroom cloud from an atomic bomb, a fire column is a little like that. Goose bumps prickled my arms. I blurted, “We need to get over there!”

Chris and Dakota laughed.

Chris explained that the three of us wouldn’t be top of mind in this critical moment. Sure, that reasoning made sense, yet I had the strangest feeling. At the sight of a smoke column, most people feel a healthy hitch in their breath and want to run the other way. You should. But all I wanted to do was run toward the fire.

Sign me up! Put me in the game, Coach. The sight of smoke made my skin tingle and my arm hair stand on end, but not with dread. With excitement.

Back at the station, my supervisor threw back his head and laughed. “You got the bug! You’re hooked.”

“Nah.” I played it off, but it was a known phenomenon: getting bitten by the fire bug. Once fire got you, they said, there was no going back.

Tony teased me for doing push-ups on the line that day and said, “You know where you might fit in? There’s a crew nearby; they’re a lot of fun. Rowdy River Hotshots.”

I figured why not? and applied. Okay, the process was a little less casual than that. I applied through the federal government’s labyrinthine online system, made several phone calls, and finally drove over the mountain to meet with Benjy and Mac, two men on the crew’s “overhead” (leadership team), to whom I made my case. I really wanted to join this crew, I swore, pledging to train all winter.

I’d been told that nobody got hired onto a hotshot crew by submitting a résumé or sending a polite follow-up email. You had to court them, woo them, flatter them, promise that this module was your top and only choice.

In truth, Rowdy River was my top choice, though mostly by default. You had to live within a certain driving distance of a crew’s station, because during fire season you’d be on a “two-hour callback.” Kelly Ramsey In that time, I could reach several crews’ headquarters: Klamath Hotshots, Salmon River Hotshots, and Rowdy River. But an ex-boyfriend who I may have low-key stalked worked for Klamath, so they were out. And I’d heard unpleasant rumors about Salmon River, whose station perched along one of the sketchiest roads in the region—no, thanks. Rowdy River it was.

The more we trained, the more excited I became. Something in me not only tolerated but loved this kind of challenge. As it turned out, I liked to suffer, and the depth of one’s suffering directly correlated to the degree of one’s euphoria at the top.

I remember what I wore to visit the station: skinny jeans, Chelsea boots, a puffy jacket. My hair hung to the middle of my back. I felt exposed in civilian clothes. The small office smelled like feet and diesel fuel, and the two men remained sitting in the only available chairs, so I towered above them while shrinking under the scrutiny of their gazes. Both were bearded; one blond and narrow-bodied (Mac), and the other dark haired and barrel shaped (Benjy). The latter’s liquid brown eyes strayed down the length of my body—not sexually, per se. I knew the look; he was assessing my physical fitness. I cursed myself for not having a shape that looked more obviously sporty. Stupid hips.

“You been hikin’?” he asked gruffly.

*

They called in January and offered me the job. Would I come? I emitted an elated and possibly squeaky yes, then hung up, feeling sick. Oh god. Now I had to actually do this. So began a phase of daily training—and continual anxiety.

Hotshot crews are physically and operationally intense. They’re often referred to as the “special forces” of wildland firefighting (although any hotshot will roll their eyes at those words). These crews tackle the most difficult and remote parts of wildfires, doing the hardest manual labor and hiking deep into the wilderness to places other crews can’t or won’t go. All wildland firefighters are tough, but hotshots have a reputation for being among the toughest.

To prepare for the rigors of the work, you had to achieve certain physical standards (as formally defined in the Standards for Interagency Hotshot Crew Operations, or SIHCO, also the name for a governing body that ensures adherence to said rules): a 10:30 mile-and-a-half run, five pull-ups, twenty-five push-ups in under a minute, and sixty situps in sixty seconds. But that was the bare minimum. You also had to complete strength circuits, six-mile hill runs, wind and hill sprints—all of which were peanuts compared to the hiking. And only the hiking really counted.

I trained with my friend Paige, who would also be joining a hotshot crew in the spring. We rose in the dark to hike. Often, we hit the top covered in sweat as the first pink light streaked the sky. The more we trained, the more excited I became. Something in me not only tolerated but loved this kind of challenge. As it turned out, I liked to suffer, and the depth of one’s suffering directly correlated to the degree of one’s euphoria at the top.

Paige left that winter, and I kept training on my own, hiking fire lines (imagine a trail, but instead of having switchbacks, it goes straight up the mountain) three times a week with the required forty-five pounds. My heart rate hit 188 and stayed pinned there for an hour as I gasped open-mouthed up hill after hill. I ran sprints, lifted weights, practiced pull-ups until I could squeeze out a few. Did thousands of sit-ups and planks. Still, I didn’t feel ready.

Not only was I anything but a natural athlete—okay, I wasn’t a weakling, though my childhood sports had been ballet, summer swim team, and figure skating—but I had almost no experience as a firefighter. Most people who came to a hotshot crew had a few fire seasons under their belt; I’d be the only rookie to both the crew and to fire. Scariest of all, while I had hoped the crew would pick up another lady or two, I learned that I’d be the sole woman and the first in nearly a decade. To many of the guys, I’d be the only girl they’d ever worked with. Just me and nineteen men who were probably faster, stronger, and more knowledgeable than I was. No big deal.

_______________________________________

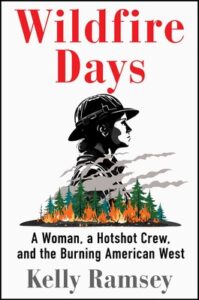

Excerpted from Wildfire Days: A Woman, a Hotshot Crew, and the Burning American West by Kelly Ramsey. Available via Scribner.

Kelly Ramsey

Kelly Ramsey was born in Frankfort, Kentucky. She studied poetry at the University of Virginia and fiction writing at the University of Pittsburgh. She cofounded The Lighthouse Works, an artists’ residency program, and later moved to Northern California, where she worked for the US Forest Service as a trail maintenance worker, wilderness ranger, and wildland firefighter. Her writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Sierra, Electric Literature, and the anthology Letter to a Stranger. She lives in Redding, California, with her partner and their dog, Rookie.