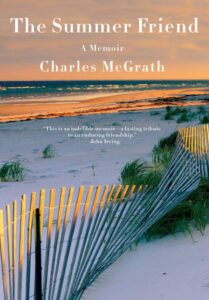

Summer Vacations Are a 19th-Century Invention of the Rich

Charles McGrath on the Ritualizing of Idleness

What we think of as summertime is really a human invention. In this country, the idea of vacations—of taking time off from work, going somewhere to get out of the heat—didn’t come along until the 19th century, and it was initially embraced by people who didn’t work all that hard to begin with. It was the rich who, especially during the Gilded Age, began to ritualize summer, traveling by steamer or train to the resort hotels, those huge wooden layer cakes, that began sprouting all up and down the East Coast.

And it was the rich—or the super-rich, really—who started building summer places of their own: “camps” in the Adirondacks, twenty-thousand-square-foot “cottages” on the cliffs in Newport. Working people didn’t get time off, and farmers, in particular, were busiest during the hot summer months. Schools let children out during the summer not so they could be idle, or because the teacher needed a break, but so they could help in the fields.

Summer didn’t have to be idle. Some early camping spots, like Oak Bluffs, on Martha’s Vineyard, or Ocean Grove, in New Jersey, had a religious component; others, most notably Chautauqua, in western New York, were founded on the idea of self-improvement, both moral and physical. But the great resorts had about them an air of exclusivity: you went there to be among people like yourself. What exactly people did at these places is—to me, anyway—a bit of a mystery.

Swimming was not an especially popular activity in the late 19th century, especially for women, who had to wear bathing costumes so cumbersome and concealing that, when wet, they practically dragged the swimmer under. There would have been sailing, and golf of course.

Around 1890 golfing became a kind of national craze among the well-to-do in America, and country clubs sprang up everywhere. I’m also guessing that then, as now, there was more sex in summer than in the rest of the year. But in the novels of the period—I’m thinking of Henry James and Edith Wharton—there’s scarcely any mention of such activities.

What people mostly did was stroll around and wait for the next meal, sort of like people in rest homes: breakfast, luncheon, tea, dinner. They also changed clothes a lot and gossiped incessantly about each other. Some of those grand old resorts still exist, and to visit one—Pinehurst, say, in North Carolina, or The Balsams in New Hampshire—is a little like visiting an old cathedral, a monument to an ancient belief system.

They all have long verandas, for strolling, snoozing, or cigar-smoking, and enormous dining rooms—the chapels, so to speak. A string quartet might drone away at one end, or a piano player tinkle out something inoffensive, while squads of uniformed waiters carried in course after course: terrapin, canvasbacks, salmon, turbot, roasts of veal and beef, followed by the jellies and aspics so popular then. Plenty of wine if you wanted it, and surely many did: they must have been bored silly.

A lot of things hastened the decline of this summer-resort culture, not least its own wasteful extravagance. But what pretty much ended it for good—except for a few grand holdouts, which now seem like 19th-century theme parks—was the advent of the automobile, which enabled people to go where they wanted, not where the railroads took them, and, especially after the war, allowed middle-class families to enjoy summer spaces of their own.

Instead of the great verandaed hotel there was the motor court, a little cluster of cabins by the highway, and, increasingly, the family place, the seaside cottage, the little cabin on the lake. For two weeks or a month every year they offered families, children and grown-ups alike, a uniquely American kind of escape, a chance to reinvent yourself: to go barefoot, look up at the stars, read the books you always hoped to, and become the person—freer, easier, tanner, thinner—you were always meant to be. If you’re like me, summer memories pile up in no particular order.

A uniquely American kind of escape: a chance to reinvent yourself: to go barefoot, look up at the stars, read the books you always hoped to…Endless car trips, your thighs sticking to the pale green vinyl of the back seat, where your brother has crossed the invisible halfway boundary and now, despite your father’s shout, “Cut it out, you two,” requires a firm disciplinary kick to the shin. Ball games and barbecues, fireworks and fireflies. Also mosquito bites, poison ivy, and sometimes—if your ice cream man was as irresponsible as ours, letting his wares thaw and refreeze—ptomaine poisoning.

One summer I threw up twenty-seven times in a row. And let’s not forget about sunburn. Back before anyone knew about skin cancer, you could fry yourself senseless in the midday glare and then stagger indoors, lobster-red and so hot you felt shivery. At night the touch of a sheet on your bare back was almost unendurable. But then, in a couple of days, you got to peel the skin from your shoulders, long strips lifting up like wax paper from a roll—a process so satisfying it was like sloughing off your own cocoon.

For a lot of people summer is connected to a particular place. That mothball-smelling rental cottage your family took every year for the last two weeks of July, the one with holes in the screens, flypaper in the kitchen, creepy-looking stains on the blue-ticked mattresses. Your old summer camp, the one with color wars, campfire ghost stories, and the teenage counselors, godlike in their wisdom and experience, who taught you how to short-sheet the beds of the new kids. (I went to summer camp for just one week when I was eleven and hated every minute, but I’m probably the exception. It didn’t help that the place my parents picked was Catholic, on the grounds of an old seminary, and that we spent almost as much time on our knees in the chapel as we did in the crumbling concrete pool.)

Or the summer place you remember best could be your grandparents’ house, where they doted on you like royalty and where you got to sleep alone in a room—no sibling for a change!—with the windows open and the white cotton curtains stirring in the evening breeze.

Summer can happen almost anywhere. You could be blissful in the rear seat of the station wagon, where you dozed contentedly, or looked out the window and played punch buggy with your sister, while on the annual trip to a national park. You could feel preposterously alive and happy at the tarmac playground where you went every summer morning and played box hockey while the little kids, shrieking, danced around in the sprinkler. If worse came to worst that special summer place could even be your own room, transformed for eight weeks or so into a sanctuary of unimaginable freedom: no homework, no bedtime, no getting out of pajamas all day if you didn’t feel like it.

For Chip that special place was the house where his mother and his grandparents had spent their summers—the place on the hill across from us. It was called Snowdon—Snowdie for short—after the mountain in Wales so beloved by Wordsworth and the other Romantics. It was a two-story shingle-style building at the top of a steep slope leading down to the water. There was a big, unkempt lawn in front, and a long, narrow porch in back.

Built in 1902, the place was once fairly grand—a relic from that era when summer belonged mostly to the well-to-do—but to keep it up had become a bit of a struggle. Chip cherished it all the same—the house and all its summer history. That was one of the first things that struck me about him—that he chose to live year-round in what was for many people just a summer town, and had made summering into something like an occupation.

_____________________________________

Excerpted from THE SUMMER FRIEND by Charles McGrath. Copyright © 2022 by Charles McGrath. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.