“Sweet, cute and with a good attitude.”

“I found her to be a very competent individual. I liked her as a person. I thought she was a person of integrity.”

Attributed to different interviewees, both statements purport to describe Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, or more specifically, Christine Blasey, the young woman these two individuals knew while she was at Pepperdine University, first as a graduate student working toward a master’s degree in clinical psychology, which she earned in 1991, and then as a visiting faculty member from 1995 to 1998.

On that 830-acre campus in Malibu, California, with a sweeping view of the Pacific Ocean, graduate student Christine Blasey met and began an eight-year relationship with a young man named Brian Merrick, who decades later would describe her to the Wall Street Journal in terms that suggested that they went to the prom together in the 1950s. This WSJ profile of Dr. Ford was published on September 19th, 2018, a week prior to her testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, in which she publicly accused Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her when they were in high school.

On the same day as the WSJ profile, the second quotation appeared in the Graphic, the Pepperdine University newspaper, and was attributed to Distinguished Professor of Psychology Cindy Miller-Perrin, who knew Christine Blasey as a visiting faculty member. Professor Miller-Perrin’s recollection suggests that Christine Blasey had more to her personhood and her personality than a pithy inscription scrawled in a high school yearbook.

Considering the reason Brian Merrick was being interviewed by the WSJ, he should have given more thought to the monosyllabic descriptors that came from his mouth. Borrow a few from Professor Miller-Perrin’s statement, for instance. Because Merrick did not or could not think through the implications of his words, I will do it for him. I will begin and end with “sweet” because Merrick undermined the credibility of both Christine Blasey, the younger, and Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, the elder—with that one word.

*

It’s a compliment! Jeez.

I’m sure that someone—perhaps even you, dear reader?—has uttered that retort in an attempt to neuter sweet, put a rhinestone collar around its neck, and call it pet.

These too are compliments: sugar, honey, candy, sweetmeat, honey bun, honey pie, sugar pie, sweetheart, sweetie, sweet cheeks, sweet lips, sugar tits, and sweet piece of ass. The slippery slope from compliment to insult begins with sweet.

By 1850, when the subjects of the United Kingdom and its unruly former colony, the United States of America, said “sweet,” they meant “sugar.”

As cultural anthropologist Sidney Mintz noted in Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (1985), there’s a distinction between the basic taste that we understand as sweet and the “ingestibles” that can trigger it. His treatise focused on refined sugar, derived from sugarcane, and how it overtook fruits and honey as the most commonly available and cheapest source of sweet in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in the Western world. Mintz’s short answers were colonialism, slavery, the Industrial Revolution, and capitalism. Here’s his timeline:

In 1650 sugar was considered a rare medicine, and if it was found in the kitchens of the United Kingdom, then it was only in those of royal households. By 1750 sugar’s culinary use had increased, but it was treated as an expensive spice and was very far from what it has become today, a kitchen staple to be measured out by the cupfuls. By 1850, when the subjects of the United Kingdom and its unruly former colony, the United States of America, said “sweet,” they meant “sugar.”

This road from rarity to ubiquity was paved by the labor of enslaved people and indentured workers on the “Sugar Islands” of the British West Indies, beginning with the empire’s “settlement” of Barbados in 1627. The increasing availability and accessibility of refined sugar—white sugar being the most coveted among the varieties—and its by-products was made possible by the subjugation and violence inflicted upon black and brown bodies. The sensorial pleasures afforded by the taste of sweet and the inhumane cruelties of slavery were inextricably twined.

This incontrovertible fact casts a grotesque light, a too- revealing X-ray, as it were, on the “little girls” in this classic nursery rhyme:

What are little girls made of? What are little girls made of?

Sugar and spice

And everything nice

That’s what little girls are made of.

Attributed in part to the British poet Robert Southey (1774– 1843), the rhyme shows the transition in sugar’s culinary role taking place: a century before, “sugar and spice” would have been oddly redundant, but by Southey’s lifetime sugar was already separating from spice, with its powders and judicious pinches, and offering itself up as a distinct ingredient to be purchased by the pound.

The rhyme also neatly captures sugar’s gendered role in the British imagination. The verse begins not with little girls but with little boys:

What are little boys made of? What are little boys made of?

Snips and snails

And puppy dogs’ tails

That’s what little boys are made of.

Southey was echoing here a divide that assigned sugar and the taste of sweet to the “fairer sex.” A connection between females and the excessive consumption of sugar was often commented upon by male “observers” of Southey’s time and onward and, according to Mintz, was put forward without research or investigation.

While the science was missing, Mintz found that there was a socioeconomic underpinning to this supposed sugar predilection. In the United Kingdom of the Industrial Revolution, sugar was, in fact, the only thing nice that poor and working-class women and their young children had in their meager, monotonous daily diet. The limited animal protein at their tables—the meats, cheeses, and fresh dairy—was reserved for the man of the house as he was the wage earner. Women and young children were habitually malnourished in order to keep these men better fed.

Without animal protein, cheap sugar stepped in to provide the bulk of feminine and infantile calories: sugar in their many cups of tea (also courtesy of colonialism); sugar in the sweetened condensed milk—an inexpensive stand-in for fresh milk and cream, which had the added benefit of being preserved and slower to spoil—in those same teacups; “golden syrup,” which was lightened treacle, a.k.a. molasses, a by-product of sugar processing, poured over their morning porridge; and sugar in the store-bought, mass-produced breads and jams that together stood in for their midday meals.

As Dr. Ford and countless examples before and after her make clear, men often blame women for being victimized and point to their bodies as the very reason for their downfall. So, yes, male observers, the fairer sex did adore and was weak for sweet, because without sugar, its cheapest delivery device, generations of mothers and their little girls and boys would have collapsed in an energy-less heap in London’s East End.

*

Before sugar, there was honey. When sugar pushed honey into a cobwebbed corner of the UK cupboard, sugar also pushed itself into the culture’s linguistic and literary imagery. Honeyed was set aside for sugared. Syrupy-toned found itself in a losing competition with sweet-talking. Here, for instance, is the 1784 version of another enduring British nursery rhyme:

The rose is red,

The violet’s blue,

The honey’s sweet,

And so are you.

Thou are my love and I am thine;

I drew thee to my Valentine.

Here’s the modern-day version of the same rhyme:

Roses are red

Violets are blue

Sugar is sweet

And so are you.

What didn’t change, according to Mintz, was the underlying sentiments and feelings associated with the taste of sweet: “happiness, well-being, with elevation of mood, and often with sexuality.”

In the realm of “sexuality” is exactly where we find Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, the elder; Christine Blasey, the younger; those sugared and spiced little girls; and the gradeschool Valentine’s Day cards, where you probably last read “Sugar is sweet / And so are you” and thought of it as high compliment.

Perhaps Brian Merrick meant to say to the WSJ that when he met Christine Blasey on the campus of Pepperdine, as the Malibu sun shone and the Pacific reached toward the horizon, he felt “happiness,” a sense of “well-being,” and an “elevation of mood,” and that he continued to feel this way during the course of their eight-year relationship, and that decades later, when he was asked to think of Christine Blasey, he thought of her still in these terms. Merrick instead reached for the juvenile shorthand “sweet.” He sugared and spiced her. He little-girled her. He sent her a Valentine’s Day card with a cartoon bear on it. With “sweet” he set the princess-pink stage for the “cute” and “good attitude” that followed. All were intended by Merrick as compliments.

*

During the period from 1850 to 1950, sugar, according to Mintz, crossed another line, from being an ingredient to being a food group in its own right: “By 1900, it was supplying nearly one-fifth of the calories in the English diet.” More accurately, sugar became a pervasive food substitute, offering the poor and working class their much-needed calories and fulfilling their desire for the taste of sweet as well as for qualities such as softness, tenderness, moistness, and a longer shelf life in their comestibles. Sugar as food could do it all and do it for less, if you didn’t take into account the utter lack of nutrition, rampant dental decay, and type 2 diabetes.

So, of course, sweet is a compliment. We prefer our girlfriends the way that we prefer our everything.

In 1961 Roland Barthes published the essay “Toward a Psychosociology of Contemporary Food Consumption” and declared that food is “a system of communication, a body of images, a protocol of usages, situations, and behavior.” Barthes was stating the obvious, but it often takes a white man’s stating the obvious to include it on university syllabi and to impart it to young impressionable minds, encouraged thereafter to think that a French academic named Roland Barthes was the first human to stumble upon this nugget of truth that any cook could have told you from the time she gathered berries or snapped the neck of a small animal and fed it to her little girls and boys.

At the open of his essay, Barthes cited the fact that Americans consumed twice the amount of sugar as the French, 43 kilograms versus 25 kilograms per person per year. (According to the US Department of Agriculture, as of 2011 sugar consumption in the US has risen to 156 pounds or 70 kilograms per person. FAOSTAT, a database of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, reported that France’s consumption in 2013 was 32 kilograms, a decrease of 1.56 percent from the previous year.)

Barthes followed his citation of a fact meant to be comparative in nature but that smacks more of shaming by asking facetiously what Americans do with all that sugar. He answers with another obvious fact: we “saturate” our foods with it, from pastries, ice creams, jellies, and syrups to foods that the French would not think to sweeten, such as meats, fish, and salads. Barthes concluded that for Americans sugar is not just “foodstuff” but an “attitude” and an “institution” that “imply a set of images, dreams, tastes, choices, and values.”

Another French author, Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, had already written the same thing in a more memorable, succinct way in his book The Physiology of Taste (1825): “Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are.” His mother probably said it to him first. Thanks, Madame Brillat-Savarin, because that observation remains devastatingly true.

Our tastes, choices, and values are literally killing us. There’s a straight-line connection between excessive sugar consumption and obesity, and obesity is one of the primary triggers of type 2 diabetes. According to the American Diabetes Association, in 2015 diabetes was the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, and 30.1 million Americans, or 9.4 percent of the population, had diabetes.

We are a country of sugar eaters. We are sweet. Actually, we are the sweetest. No country in the world consumes as much sugar as the United States, with 126.4 grams of sugar per person daily.

So, of course, sweet is a compliment. We prefer our girlfriends the way that we prefer our everything. This was why Brian Merrick didn’t have to think twice. The Christine Blasey he had known was “sweet, cute, and had a good attitude.” Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, the woman she had become, the woman who would have to ask for a bottle of Coke with its 65 grams of sugar in the form of high-fructose corn syrup in its 20 ounces in order to keep her energy level up—nutrition be damned.

Dr. Ford had work to do and no one was going to give her a plate of animal protein—as she withstood the four hours of questioning in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, that woman would have been better served by a steak, medium-rare, and better complimented by “competent” and “integrity” or, most accurately, “person.”

__________________________________

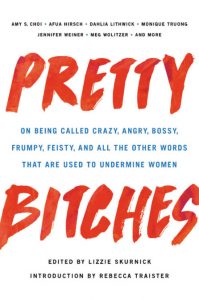

From Pretty Bitches. Used with the permission of the publisher, Seal Press. Copyright © 2020 by Monique Truong.

Monique Truong

Monique Truong was born in Saigon and currently lives in New York City. Her third novel is The Sweetest Fruits (Viking Books, 2019). Her first novel, The Book of Salt, was a New York Times Notable Book. It won the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award, the 2003 Bard Fiction Prize, the Stonewall Book Award-Barbara Gittings Literature Award, and the 7th Annual Asian American Literary Award, and was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award and Britain’s Guardian First Book Award. She is the recipient of the PEN/Robert Bingham Fellowship, Princeton University’s Hodder Fellowship, and a 2010 Guggenheim Fellowship.