Su Cho on Beginning Her Poetic Journey

"I never intended to become a poet. It’s just that I was addicted to feeling things strongly and then feeling nothing at all."

Notes on Beginning Again, Again

For my first poetry teacher, Molly Brodak

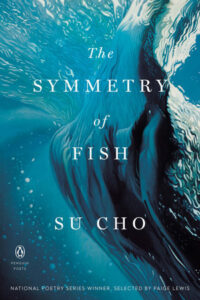

I never intended to become a poet. It’s just that I was addicted to feeling things strongly and then feeling nothing at all. Though it would take me a long time to realize this. When I think about writing The Symmetry of Fish, all I can see are the bursts of passion strung along between all that I didn’t, and still don’t, know how to feel.

*

I think about my early teachers and feel compelled to apologize—I wish I could shake my old self awake sooner.

*

Here are some things I’m sure of:

Language begins in my body, my chest, my toes, and travels to my mouth.

Language is a bodily act.

Memories are fraught. We add embellishments in our writing, little signals so we can more accurately convey the emotions we wanted to preserve. These embellishments feel like skeuomorphs we hoard and pack into our words so we can try to feel them later.

When I think about writing The Symmetry of Fish, all I can see are the bursts of passion strung along between all that I didn’t, and still don’t, know how to feel.Skeuomorphs—a word I only remembered when I was going through my old live.com email, trying to find ways to talk about the indebted relationship I have with Molly. An archive of nostalgia it feels bittersweet to comb through, our emails consist of me asking for templates and letters. Letters of recommendation, sample syllabi because I was teaching for the first time. She invited me to submit to a lit mag she ran and kindly published the bare, ghosty poem I sent. Later, I was an editor soliciting poems from her—“Post Glacier” is one of the poems she sent. I thought I was showing my gratitude—could we meet at AWP Tampa? She always obliged.

Another time, I asked her how she was and she replied with a link to a blog she was going to start updating more. Here I am, almost a decade later, reading those posts, relearning what a skeuomorph is, how she said literature is full of them. I realized just how funny she was and I wish I could talk to her now because I feel like I know enough to catch it. But I wouldn’t have caught up with her. Good teachers don’t remain stagnant. Still, here I am, having learned to laugh alone at my own jokes, all those baffled students who can’t tell what’s funny. Mentally, I add, yet. But perhaps that is where I learned not to be shy of my own laughter in the classroom—even when our students haven’t caught onto what’s funny. Mentally, I add, yet.

*

Every start to this essay feels selfish, so I delete it, then force myself to put it back.

*

My fiancé and I recently moved to South Carolina to teach. On our first walk through the university’s “Experimental Forest,” as I’m trying and failing to talk through how I will frame my book, my fiancé tells me that I’m always judging the present against some idealized past. He is referring to the way food will either make or break my day, and if it breaks, then only food can fix it. But one can eat only so many times a day. He has a good point because it makes sense to us. This is true. It’s the way I can pick a place apart after moving there.

*

I can say I was becoming a writer when I was in the presence of a real writer, in an empty office with nothing but an askew photocopy of “Things to Think” by Robert Bly thumbtacked to the wall. During office hours, or when I would be that student and show up just to chat, I can hear her laugh, “This was the only thing here when I first walked in” or “There was a stack of these in the desk drawer and I decided to put one up” or “I brought this in here and thought, why not?”

For someone who thinks about the past constantly, I am very bad at remembering it.

*

I wanted and still want to impress her with my first book. The people I really want to read it, can’t. When I read the news of her death online, I thought of our last in-person meeting at AWP Tampa. She had to be on a panel right after our lunch and so we met at a nearby hotel restaurant, ate something simple. I wanted to say so many things but was trying to keep it cool. This was during a time when I was in awe of everything and everyone. She showed me otherwise—that we can say how we feel about certain things, that some things are full of nothing, and I wish I had the courage or even the wherewithal to ask, how?

Those office hours talking about writing sometimes, but mostly not, changed my life. I remind myself of this whenever I feel tired around my students. I must’ve been a pain the ass. When I try to remember what we talked about, it’s like trying to press your ear against a wooden door. I can feel shapes of office hours—the way she spoke so plainly about herself, about how she would never love again, that marriage was stupid, about her father, and with a laugh that made me think oh yes, this silly thing again, and I just sat there. No, I’m sure I reacted—I don’t remember how.

During her two years as a creative writing fellow at Emory, she recommended three books to me: I Love Artists by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Madness, Rack, and Honey by Mary Ruefle, and The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson (yes, that one). I can’t write like any of these writers but I loved how they felt like a mystery to me, and these are the books I go back to whenever I feel stuck.

*

I can’t help but ask this question as if it’s a secret: What is joy? Do you feel it all the time? If no one responds, I fill the silence by saying for someone who’s supposedly a poet, I’m dead inside. I believe it’s the funniest thing I can say.

My favorite refrain is I have too many thoughts. It’s a mental dog-earing of personal opinion, but I never follow up on it. I realize I never talk about anything, really. I’ll write about it years later, and I prefer it that way. But you’re a writer! Someone will say. Yes, I process things incredibly fast and incredibly slow. You’ll just never know which track I’m on.

But there’s a line by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge in her poem “Hearing” that never fails to demand my full attention and it calls me out, highlights my own flippant sayings.

A voice with no one speaking, like the sea, merges with my listening, as if imagining her thinking about me makes me real.

And another one from “Nest.”

A margin can’t rot, no bloated outline around memories of witness, the way origin in the present is riddled with holes.

*

During a writing exercise, I write alongside my students, a habit she taught me.

There is nothing much to say about joy—if you have to question it, you have already failed. Joy is not real because everyone calls it something else.

When we go around the table to read our “short lectures” after Mary Ruefle aloud, I feel compelled to read mine. I don’t know what I expected. I do, though. I wanted laughter. I could make myself hear her laugh. But they just turned their heads toward me and gave me a polite nod, and I am grateful.

*

On skeuomorphs and poetry, Molly writes, “It’s a steady symbol of something we remember, something ‘real’—those pesky messes of the world: events, feelings, ideas, people.” I love how she catches the vast things we write about, I write about into “pesky messes,” like something we want to take a dustpan to and clean it all up. Then, hope the messes come alive while we sleep.

Symbols feel too heavy and so I’m drawn toward sound, origin in the present is riddled with holes, but for me it is sound that emerges through those holes.I am shy about these steady symbols of how I remember my own history. Symbols feel too heavy and so I’m drawn toward sound, origin in the present is riddled with holes, but for me it is sound that emerges through those holes. The sound of 가시thorns, splinters, fishbones; 밤 the sound of night, of chestnuts, the sound of my mouth open, pointing to my throat, uttering the last sound of girl over and over again.

*

There’s a final book I always forget as a gift. It was the end of Molly’s two years at Emory, and I was sad. Before the last class, I went to the university bookstore and in search of a gift for the person who told me what an MFA was, how I could be a writer, to always try. I wanted it to be personal so I settled for some bookplates and fancy colored pencils. I don’t remember if I wrote her a card. And I think perhaps it was a week later, when final portfolios were due, she gifted me If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho translated by Anne Carson with a card tucked in the middle.

Su–

Just think—Sappho was going through the same things 2700 years ago! Remember you belong to this long line of poets—you are never alone.

keep in touch! Molly B

And we did.

___________________________________

The Symmetry of Fish by Su Cho is available from Penguin Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.