Styling It Out: Or, Using Your Sunday Best as Armor Against Hostility and Racism

Mike Gayle on Sartorial Optimism

It was the late 80s: I’d just turned eighteen and, desperate to establish my own identity, I had decided to reinvent myself before meeting friends in town. De La Soul had just released Three Feet High and Rising and on that particular morning, as a tribute, I’d gone to the barbers and asked for a flat top similar to that of band member Posdnuos.

To complement my new haircut, I took it upon myself to spray paint a CND peace sign on an old baggy t-shirt which I’d proudly matched with an oversized denim shirt, cream tailored Bermuda shorts and basketball boots. I genuinely believed I looked incredible, cool and edgy. And it was this new incarnation of me on my way to the bus stop at the end of the road that spotted my dad coming the other way.

My dad didn’t really do casual outside of the house, and this day was no exception. Despite the fact that it was a Saturday and he wasn’t at work, he was dressed in a sharp navy blue pinstriped three-piece suit, crisp white shirt and tie. He even had a red silk handkerchief poking out of the front pocket of his jacket. As he got closer, I couldn’t help but be struck by how differently we were dressed.

He must have been thinking exactly the same thing, taking in my outfit and wondering what on earth had gotten into his son. When he finally reached me, he didn’t even pause to say hello. He just smiled and nodded as if we were only vague acquaintances before carrying on his way, leaving me chuckling to myself on the pavement.

I share this story, not to illustrate the fashion gap between the generations but rather to bring into focus a more pressing question: why was a middle-aged Jamaican man voluntarily choosing to dress in a three-piece suit on his day off?

Against this sort of poverty, it seems only natural that when they finally had a little hard-earned disposable income of their own, they would use it to express themselves through clothes.

It wasn’t just my dad who was like this; my mum was, too. She was forever being complimented on her elegance and style—even by complete strangers on the bus, even when half the time she hadn’t been anywhere more remarkable than the supermarket.

For as long as I’ve known them, both my parents have been snappy dressers, always immaculately turned out whenever they left the house. On one memorable occasion, while visiting my wife in hospital after the birth of our eldest daughter, my father was mistaken for a consultant doing ward rounds simply because he was so smartly dressed.

And when my TV presenter middle brother announced that he’d been invited to a garden party at Buckingham Palace and wanted to take Mum as his plus one, she didn’t bat an eyelid. Instead, she disappeared upstairs only to return carrying a chic powder-blue ensemble complete with hat, matching shoes and handbag, casually declaring, “I’ve been waiting for a good excuse to wear this!”

That’s my mum’s wardrobe for you, ready for all eventualities, even ones involving heads of state. Her approach to buying clothes speaks volumes about her. It’s like Kevin Costner’s character says in Field of Dreams: “Build it and they will come.” Except in my mum’s case it’s more, “Buy the fancy outfit even though you don’t need it and the perfect occasion to wear it will arise.”

In part, I think, my parents’ love of fashion stemmed from growing up in rural Jamaica in the 1940s. They didn’t have much in the way of clothes, perhaps one set for everyday wear and one for Sunday best. I’m almost certain that neither of them owned a pair of shoes until they were well into their teens. Against this sort of poverty, it seems only natural that when they finally had a little hard-earned disposable income of their own, they would use it to express themselves through clothes.

Another influencing factor is one I’ve already mentioned, that of Sunday Best: the idea of having a set of finer clothes reserved for special occasions like attending church, weddings, or funerals. I imagine that when your everyday wear was patched and threadbare, the knowledge that you possessed an outfit that was the complete antithesis would have been emboldening somehow, reminding you that you weren’t just one thing, that your poverty didn’t always have to define you, that every now and again, you could look like a million dollars even if you didn’t have two pennies to rub together.

But many people, my parents included, found that one of the best ways of rising above the tide of hostility and racism that greeted them was to always present the best versions of themselves.

You can see this thinking in the black and white photos of the first West Indians arriving in England on the ship MV Empire Windrush at Tilbury dock on June 22, 1948. Responding to the call from the “mother country,” people from Jamaica, Trinidad, Tobago, and other islands left behind everything they knew to help fill post-war UK labor shortages. And boy, did they turn up looking smart!

Young men in suits, ties ,and trilbies with shoes so highly polished you could see your reflection in them. Young women in beautiful dresses, hats, and immaculate white gloves. Even the children came wearing their very own Sunday Best, everything neatly pressed and spotlessly clean, long white socks pulled up to their knees. They’re all dressed like they’re on one big church outing, looking so full of hope and expectation, much of which would sadly be lost in the face of poor living and working conditions from the country which would turn out to be far less maternal than they’d been led to believe.

But many people, my parents included, found that one of the best ways of rising above the tide of hostility and racism that greeted them was to always present the best versions of themselves. When my mum and dad turned up at school parents’ evenings more smartly dressed than my teachers, it sent a message: we have high standards and expect the best. When they stepped out of the front door looking like they were on their way to the opera, it said to all around: we might live in a cramped council house in a poor area of Birmingham, but we’re on our way to better things, just you wait and see.

Perhaps that was why my dad was so disappointed when he encountered me on the street that day dressed like the fourth member of De La Soul. He must have thought that I didn’t get it, that I didn’t understand the importance of presenting your best self to the world.

But thanks to my parents, I had more freedom to explore and express my best self. Even now, in my early fifties, rather than fading into the background in regulation “dadwear,” I still like to push the envelope a little, much to the amusement of my two teenage daughters. I’ll happily dress like a misplaced trawler man in a thick woolen fisherman’s sweater, watch cap, and baggy Nigel Cabourn dungarees while standing in line at the post office. I can be spotted donning a huge sheepskin-lined vintage Swedish army coat with collars so massive that I resemble Count Dracula while grabbing a bite in McDonald’s.

And while in retrospect, long socks and Bermuda shorts were never a good look, I can appreciate the fact that eighteen-year-old me had the confidence to try it, a confidence that was actually a rather enduring inheritance from both of my parents.

_____________________________

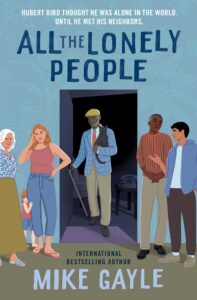

Mike Gayle’s novel, All The Lonely People (Grand Central Publishing) is out now in paperback.

Mike Gayle

Mike Gayle was born and raised in Birmingham, UK. After earning a Sociology degree, he moved to London to become a journalist and ended up as an advice columnist for a teenage girls’ magazine before becoming Features Editor for another teen magazine. He has written for a variety of publications including the Sunday Times, the Guardian, and Cosmo. Mike became a full-time novelist in 1997 and has written thirteen novels, which have been translated into more than thirty languages. After stints in London and Manchester, Mike now resides in Birmingham with his wife, two kids, and a rabbit.