Studies in Unmeaning: On Thomas Pynchon’s Detective Fictions

Adrian McKinty Reads Pynchon’s Hardboiled Trilogy

Thomas Pynchon’s late style, beginning with Inherent Vice (2009) and continuing through Bleeding Edge (2013) to Shadow Ticket (2025), represents a curious and deliberate narrowing of his fictional field. The vast encyclopedic architecture of Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) or Mason & Dixon (1997) gives way here to a series of detective fictions each set in a distinct historical moment, each featuring a reluctant investigator sifting through the wreckage of cultural paranoia.

Pynchon is clearly a huge fan of detective fiction and quotes approvingly from the genre while not quite wanting to immerse himself fully within it. In Pynchon’s detective books, the form becomes a kind of laboratory for testing what is left to us when information has replaced knowledge and where the logic of detection, the very idea of a solvable mystery, has itself decayed.

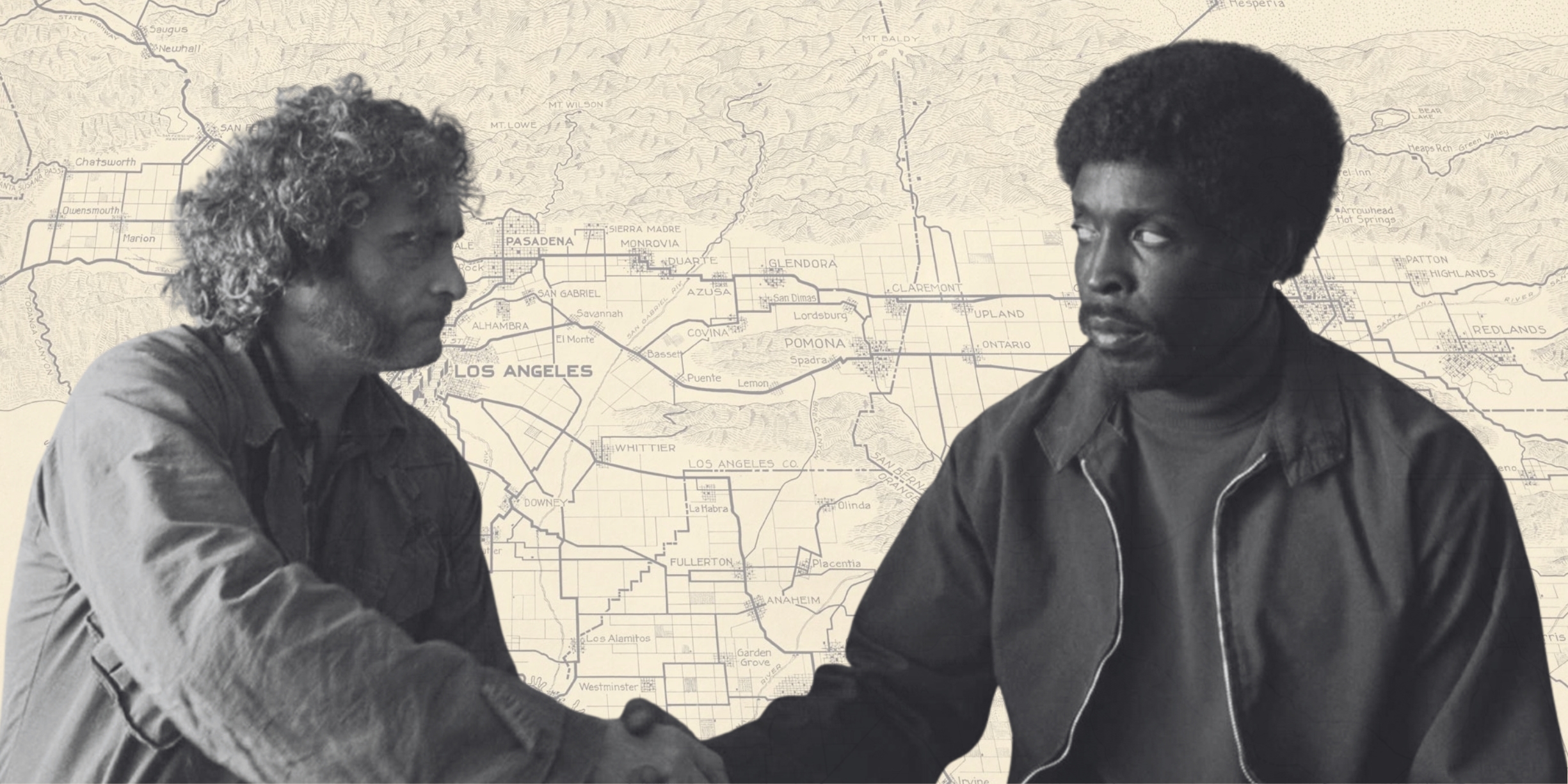

Inherent Vice is the sunniest and most deceptively innocent of his three detective books. Set in the post-Manson haze of 1970s Los Angeles, its private eye, Doc Sportello, shuffles through the ruins of the counterculture like a spaced-out Orpheus. The novel takes the scaffolding of hard-boiled noir—the missing girl, the corrupt land deals, the cops, surfers and gangsters—and filters it through marijuana smoke and Pynchon’s wistful sense of a lost utopia. The genre’s apparatus remains, but the will to solve the actual bloody case more or less collapses: Doc’s “investigation” becomes an allegory for a culture losing its coherence, its ability to connect cause and effect. The detective, once the exemplar of reason, drifts here into a fog of unknowing. The detective story, once the paradigm of total comprehension, becomes a parody of itself.

I suppose some critics might think of Inherent Vice as “Pynchon Lite,” but for me it is also one of the funniest and most enjoyable of Pynchon’s works and is one of the gateway books I give people (along with The Crying of Lot 49) who are looking for a gentler way into Pynchon’s world. Inherent Vice’s looseness and laughter, its refusal of grandeur is strategic. Beneath the novel’s slapstick surfaces lies the melancholy recognition that detection is perhaps no longer possible because reality itself has become so weird.

When literary fiction types lose touch with the demotic their books go bad.

Pynchon’s early 70s Los Angeles (half hallucination, half real estate scam) is both paradise lost and an early symptom of the delirium to come. The novel’s nostalgia for a simpler time, one that still believes in clues, renders it a kind of elegy for conviction itself. Robert Altman’s version of The Long Goodbye (1973) shares much of the same tone, milieu and gags and, incidentally, would be a great double bill with Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice (2014) if you’re looking to curate a movie night.

By Bleeding Edge, Pynchon’s detective has re-emerged, no longer in the haze of acid and pot but in the flicker of screens. Maxine Tarnow, the Upper West Side fraud investigator, moves through a Manhattan already haunted by 9/11 and by the virtual phantasmagoria of the early internet. If Inherent Vice treated the 1960s’ collapse as farce, Bleeding Edge treats the turn of the millennium as deconstruction: code replaces substance and encryption becomes both plot and structure. The novel’s cyber-subterranean realm is both a literal and figurative underworld, a digital unconscious where fragments of erased histories flicker, come to life and threaten to kill you.

Here Pynchon attempts to rewrite his noir investigation as something that William Gibson might recognize as a plot. The clue has been replaced by the data-trace; the villain by the algorithmic network; the crime by the infinite regress of surveillance itself. The mystery is not who did what to whom, but how, in a hyperreal economy, anything can still be said to have occurred. The novel’s humor, puns and sitcom rhythms can’t conceal the anxiety of its form. Whereas Chandler’s Marlowe pursued meaning through corruption, Tarnow swims in a world where corruption and meaning are indistinguishable. Bleeding Edge thus marks Pynchon’s most overt confrontation with the collapse of ontology into information. It is both detective fiction and its preposterous autopsy. There are, of course, the usual ridiculous gags and puns and a long set up for a Scooby-Doo joke that might be the stupidest and funniest in all of Pynchonland.

I asked Salman Rushdie about Pynchon once in an interview that detoured for far too long (for my editor anyway) into cricket and baseball. I told Rushdie that I’d heard a rumor that he, Pynchon and Don DeLillo had a box together at Yankee stadium. Rushdie scoffed at that idea, if this were true, he said, the three of us would sit somewhere along the third base line. Pynchon, Rushdie and DeLillo may hobnob and sometimes write about elites but they are not of the one percent. When literary fiction types lose touch with the demotic their books go bad. Pynchon’s excursions into detective fiction are, I suppose, another form of this idea.

Thomas Pynchon’s latest novel, Shadow Ticket, set in 1932 Milwaukee, takes place in a landscape of industrial ghosts, strike-breakers, fascist sympathizers and absurdist cabals. The novel sometimes reads like a prequel to Gravity’s Rainbow; the private eye, Hicks McTaggart, moving through a universe already vibrating with the same febrile harmonics that will later detonate in the Second World War. Yet what animates the novel isn’t really accurate historical reconstruction but the sense of genre devouring itself. Pynchon stages detective fiction against its own obsolescence: the clues proliferate like symptoms, the plot disintegrates into digression, and the very act of reading becomes a kind of archeological farce.

Taken together, the three books form a trilogy of epistemological uncertainty.

If Inherent Vice lamented the fading of the 60s, and Bleeding Edge charted the virtualization of the present, Shadow Ticket seems to weep for history itself. It is the most self-reflexive of the trio, a baroque palimpsest of Pynchon’s own tropes. The secret societies, cheese-based humor, ludic comedy, linguistic excess all folded into a metafictional investigation. It is taxing to read at times which is possibly the point of the whole exercise, with entropy and exhaustion appearing to be two of its major themes.

Taken together, the three books form a trilogy of epistemological uncertainty. Each marks a different phase in the history of information: the analog haze of the 1960s, the digital pre-9/11 netherworld, the proto-industrial conspiracies of the 1930s. And across them, the detective—once Modernism’s heroic empiricist—a figure of melancholy drift, a leftover from a world that still believed in beginnings and ends. These books can be read as comedies of cognitive dissonance or as melancholy elegies for the very possibility of closure.

If Gravity’s Rainbow embodied the Enlightenment dream of total knowledge these late works embody its inversion: the recognition that knowledge itself has become noise. They suggest that parody (to steal a line from British comic Stewart Lee) is the only remaining mode of sincerity. Pynchon, in his seventies and eighties, has not grown sentimental so much as stoically absurd. The detective, stumbling through sun-bleached California, the pre-dotcom Manhattan, or the proto-fascist Midwest, is merely his latest avatar of bewilderment.

Whether this trilogy represents a diminishing or a refinement depends on one’s patience for the joke. When Pynchon won the National Book Award he sent stand-up comedian “Professor” Irwin Corey to accept on his behalf. Corey’s improvised bullshit has withstood the test of time and remains, like Pynchon’s dad jokes, pretty funny. The early Pynchon sought to map the whole paranoid system; the late Pynchon inhabits its ruins and perhaps what remains—the slapstick, the style, and the pathos—is a “shadow ticket” to a reality that has already vanished. Maybe Pynchon is saying that the classic mystery was never meant to be solved at all, only mourned. Or maybe he’s saying, just relax and enjoy the cheese jokes, puns, and Scooby-Doo material.

Adrian McKinty

Adrian McKinty was born and grew up in Belfast, Northern Ireland. He is the author of the DI Duffy series of detective novels and the 2020 NYT bestseller, The Chain.