Stuck in a Spaceship: On The Expanse and Redrawing the Lines of a Body

Allison Wyss Considers Bodies in Space and Our Communal Body on Earth

In the bleakness of the past few years, it was space TV that saved me. A closed, suffocating spaceship resembled quarantine, while the vastness of the universe let me dream of release. Then I found The Expanse, which put me right back in my body—but changed.

The Expanse is set in a future in which human beings occupy not just Earth but also Mars, which they’re struggling to terraform, and the Asteroid Belt, which the lower classes mine for minerals. These three pockets of the solar system have been populated for long enough that distinct cultures have developed, and wars sometimes break out between them.

Throughout the series, we follow a plucky band of outcasts who find a fancy spaceship and a dangerous clump of protomolecule. These characters are from Earth, Mars, and the Belt, and they form an unlikely family to save humanity from an ancient but re-awakened alien threat.

Although the story is intriguing, what most interests me is the show’s persistent and realistic portrayal of human bodies, and how living in space—or not—directly affects their function, putting pressure on the bones, organs, muscles, and blood vessels.

In other space narratives, we might get a flip mention of bodies, but they’re almost never integral to the way characters truly live. In one episode of Battlestar Galactica, repeated jumps wreak havoc on the physical wellbeing of the characters—or maybe it’s just lack of sleep. Afterward, the bodily effects of space travel are mostly forgotten. Most movies are the same. Aliens might have exciting powers or green skin, but it’s usually played for visual effect, and we don’t learn what it feels like to be in a different sort of body.

Of course, Carrie Fisher was truly and historically strangled by her bra due to gravitational strangeness—and moonlight—but that’s the actor, not the character. (We miss you!) Otherwise, Star Wars bodies seem to function fine, harnessed or not, hurtling through space or grounded on planets of varying gravitational pulls. And somebody tell me, how do their feet stay on the ship’s floor?

In The Expanse, it’s explained: magnetic shoes. Otherwise, they float. Gravity isn’t “solved,” but characters work around the lack of it.

In the real world, we’ve built our systems to accommodate one type of body, but we could choose to make it accessible for other sorts, too.

And there are dire ramifications to having a body in space. Healing, for example, requires gravity. Despite advanced medical technology, if there’s no downward pull, the body can’t heal itself. Some ships can make a sort of gravity substitute, but the equipment is expensive and most don’t have it. The intense speeds of space travel can also cause fatal blood clots.

Belters, who grow up without gravity, develop different bones, different frames. The physical reality of living in space embeds permanently in their bodies.

In fact, privilege locates very specifically in the body. Earthers are in many ways the elite, and that builds directly into their bones and musculature. Characters who build their bodies in high gravity can handle low gravity or none. But Belters can’t go to high-gravity planets without intense training and invasive medical interventions, which don’t always work.

It’s not only plausible that gravity affects a body’s development, but metaphorically resonant. In the world we currently inhabit—you know, Earth—privilege and oppression manifest in bodies just as seriously. Access to healthcare is an obvious example, but there are many others. Trauma, of course. And nutrition, clean air and water. All of the many ways a living situation can be healthy or not.

There’s also alignment with the ways that the bodies we’re stuck in affect what the world grants or refuses to grant, including mobility, accessibility, safety, and acceptance. Bodies are frequently the means by which our society limits people and builds unjust hierarchies that give power to some while denying it to others. Race, gender, sexuality, disability.

It makes scientific sense that the folks on a spaceship become a family—a body.

And yet, those Belters. It’s only when they try to go elsewhere, to a world built for others, that they have problems. Living on the Belt, in the ships and satellites they’ve created for themselves, their bodies have advantages over those born on Earth—for starters, they can better handle the speeds required of space travel.

In the real world, we’ve built our systems to accommodate one type of body, but we could choose to make it accessible for other sorts, too. Our tools have always been extensions of our bodies. What is a hammer but a more efficient fist? What is the rest of the world but an extension of those tools, an extension of our communal body?

Maybe in some utopian future, we’ll have the technology to transcend our bodies. (I’m not sure I’d want to.) But for right now, human beings are stuck in them, with all their messiness and all their complications. And so we change them, we build them into better things, we incorporate our tools into them. We use the tools we have—clothing and cosmetics, nutrition and exercise, hormones, prostheses, dentistry and contact lenses—to become our best or most true selves. Why not use all the tools?

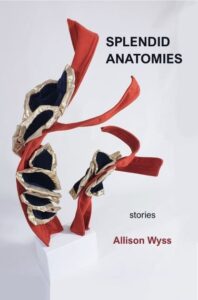

That’s what I find myself writing about. Splendid Anatomies is about the ways different characters try to claim their own bodies, through modifications, enhancements, magic, sometimes even through destroying them. My characters are embodied, and always striving to figure out what that means. They’re not all successful! But the struggle itself is glorious, I think, and revelatory. Characters rebuild their bodies to affirm their identity, sometimes in mundane ways and sometimes grotesquely, adding breasts, removing moles, spewing their organs across a cottage floor. They persistently re-draw the lines of what they consider self.

Striving to make your body more truly your own is a powerful and worthwhile endeavor.

We’re all cyborgs. Our smartphones add remote brain space. Paper and pencil do, too. Medical intervention affects our bodily functions, keeps us alive. The idea of taking technology (or anything, for that matter) and making it a part of your body is not that radical. Yet it’s an extremely powerful way of claiming your own self. When you change your body, it often becomes more you. If you get a tattoo or have cosmetic surgery, you become more authentically who you’re meant to be, because you made that choice about your body. Sometimes, maybe, you get it wrong. But striving to make your body more truly your own is a powerful and worthwhile endeavor.

Let’s go back to that band of outcasts from Earth, Mars, and the Asteroid Belt. An unlikely family, they’re bonded by a mission and by sharing an enclosed spaceship. But this isn’t just metaphorical—it’s physical.

Whenever humans sit close together, we share bodies. Flakes of me enter your permeable skin, your permeable ears and nose, your permeable brain. We share germs, pheromones, shedded skin cells. When we share ideas in a virtual space, we rewire each other’s synapses, those physical parts of our physical brains. When you read my words, I’m rewiring your physical brain. And so tell me—are there borders to a body?

It makes scientific sense (and fictional sense and social sense) that the folks on a spaceship become a family—a body—regardless of the accident of what planet or asteroid they were born on.

People are good at othering, at drawing a line that says “you are not me,” but when we understand those lines are changeable, we can draw them in new ways. In TV shows, when the writers want to shake things up for a new season, they redraw the lines of family. A new threat can throw friends together with enemies, can forge new alliances. A sworn enemy becomes an ally, just as plausibly as a lifelong friend betrays. We do this in the real world, too.

I think of public health and the difference it would make if we could care about our extended body—our whole world-wide community—instead of one individual sack of blood and organs and bones. If this one planet is our spaceship, we’re stuck on it together.

_____________________________

Allison Wyss’s Splendid Anatomies is available now from Veliz Books.

Allison Wyss

Allison Wyss’s short story collection, Splendid Anatomies, was published by Veliz Books in 2022. Her stories have also appeared in Water~Stone Review, Cincinnati Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, and many other places. She writes about craft, books, and TV for the Minneapolis Storytelling Workshop and the Loft Literary Center, where she also teaches classes.