Stories Where Nothing Happens in the Middle of Nowhere: A Reading List

Michael Martone on Placeless Stories and “Not Narratives”

When I first read “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” by William H. Gass, I was shocked by two things: first, that he wrote a 36-page “story” where nothing happens (a philosophy professor moves to a small Indiana town after breaking up with a lover and thinks about it), and second, that he wrote about Indiana.

Now, fifty years later, I am still writing (and still reading) “stories” in which nothing happens and those that are set in the placelessness of the American Midwest, a region famous for not really knowing where it is.

I surround “stories” in scare quotes because these “stories” have no beginnings, middles, or ends. They resist the existential linear nature of written language. Instead of the line of Freytag’s triangle, they are more blot, cloud, atmospheric. “Experimental”? No. They are akin to the actual traditional American “story.” Think of Poe and his strategy of composition, the Unity of Effect.

The following is a litany, a collage, an amorphous arrangement of “fictions,” contraptions constructed of litanies, collages, and amorphous arrangements that create “not narratives” of unities of effect.

*

Glenn Meeter, “A Harvest,” from Innovative Fiction: Stories for the Seventies

(Dell)

The nowhere where “A Harvest” is set in another heartland: the breadbasket, a dryland farming wheat-belt spanning from the Dakotas to Oklahoma. The philosopher narrator neatly erases the “I” with: “You, like myself, are no tiller of soil, no giant of the earth, no warrior, pioneer, entrepreneur, no Hemingway hero, either…, but more of an Updike sort of fellow, a dealer in certain abstractions propositions, possibilities, promotions, situations….” You and The You drive north to south and back again. “A Harvest” is a harvest of the nominative, a bumper crop of nouns.

Janet Kauffman, “Anton’s Album” from Obscene Gestures for Woman

(Knopf)

When one forsakes the narrative line—gives up the dig, set, and spike of story—how does one shape what seems to be a swarm of prose, a murmuration of murmuring? Numbering often helps. Janet Kauffman numbers the sections of “Anton’s Album” from 1 to 16. Not the skeleton of story, but it is a bit of cartilage: the curve of the ear, the connective tissue in load bearing joints. Wait, why 16? Why not 13 or 17? The squareness of 16 resonates on some level? A cadence of a double-quick march? A square dance? Four beats through the four chambers of the heart.

David Means, “Michigan Death Trip” from The Secret Goldfish: Stories

(Harper Collins)

“Michigan Death Trip” presents in nine sections. Its title alludes to Wisconsin Death Trip, a book that ruminated on 19th-century photo albums of dead Wisconsinites posed in their caskets. The “album” is another arrangement of non-narrative prose. Each section has its own title. The suggestion is of a stack of carte de viste, stereopticon cards. Numbering still propels us forward, a page-turning tool, but the technology of the book allows for going backwards, skipping around, shuffling the deck. There are many ways to end. And on the way, nine little deaths to survive. Gestation, doled out by the number nine.

Lon Otto, “Submarine Warfare on the Upper Mississippi” from A Nest of Hooks

(University of Iowa Press)

Nothing happens here. In World War II, a German U-Boat stealthily made its way up the Mississippi River and took up a station, submerged much of the time, off the Twin Cities, staying there for years. Like the philosopher in Gass’ fiction, the U-Boat commander does nothing once he has arrived but think about static; this static situation. Stasis versus mobility is the great drama of America. In the Midwest it mutates into the Indy 500, an iconic ritual of going nowhere fast. “Poetry makes nothing happen,” Auden writes. That can be read two ways: Nothing happens, and nothing happens. Both can be held in the mind, buoyant, simultaneously.

Kellie Wells, “Secession, XX” from Compression Scars

(University of Georgia Press)

When I opened a new Word document to type this list, it defaulted to an 8.5 x 11 page with a single column. I am typing with an incredibly powerful typesetting machine, and still it assumes that I use this machine as I would a 19th-century typewriter. The convention of narrative realism is that typewriter writer produces a transparent text, a text the reader sees through, that does not call attention to itself as a text. Instead, Wells splits her chromosomal fiction into two columns, uses different fonts, and demands that the reader remembers that the reader is reading.

Clarence Major, “Mobile Axis: A Triptych” from Fun & Games: Short Fictions

(Holy Cow!)

Yes, we read words in an ordered order—one after the other, left to right, top to bottom (in English). But the lyrical writer cussedly resists. What if a fiction (a story) could be absorbed all at once like a painting? Or make the eye move along divergent paths? There are strategies. Brevity is one—a block of text on a single page. Collage another. The writer Clarence Major is also a painter. Can the writer of fiction be an abstract painter? Words are already abstract. If I write “cat” you will imagine a four-legged furry animal, a tracked vehicle but not ink on a page or pixels on a screen.

Louise Erdrich, “Fuck with Kayla and You Die” from The Red Convertible: Selected and New Stories, 1978-2008

(Harper Perennial)

With Louise Erdrich, it’s all about economies of scale. Though she is the most narrative of the writers here, her debut collection of stories, Love Medicine, was itself a collage, a “novel” of linked stories. Erdrich’s stories may be story-like, but they are also collaged fragments of much larger mosaic frieze of a Mandelbrot set. She also fractally addresses the way that writing competes with competing narrative delivery devices like movies, radio, TV, and more. What can writing do that the other media can’t? Expand… Expand… Expand… Expand…

Susan Neville, “Night Train” from In the House of Blue Lights

(University of Notre Dame Press)

Mythology employs narratives that the audience already knows, so that the plot’s points are a given and don’t have to be retold. This fiction’s static elaboration is of Indiana Klan leader D.C. Stephenson’s fall via his torture of Madge Oberholtzer (who died subsequently) on the Night Train from Indianapolis to Chicago. No plot but blot. The fiction’s structure is stain. And like a stain, its application—first sanding it away, followed by the reapplication of the surface anecdote—creates a profound sense of depth. Fictions are like the steam engine’s doubled motion: The apparent glide of the train on a track and the frenetic movement of the driving apparatus. A fiction moves and it also moves.

Ander Monson, “Other Electricities” from Other Electricities: Stories

(Sarabande Books)

In addition to augmenting the fictional environment with illustrations, “Other Electricities” by its very nature erodes the boundaries of generic genre. Short fiction is a voracious form. It consumes other forms. This could be thought of as a fictive memoir found within the pages of a physics textbook. All of these fictions in which nothing happens and a character thinks about the nothing happening might register as fictive essays, prosaic poems, or lyrical narrative. The categorizing of the category is what defines this category. Electricity we think moves by wire, by line. But turn it on and it is on everywhere at once.

Lorrie Moore, “How to Become a Writer” from Self-Help

(Knopf)

In other “stories” that are really “fictions” in which nothing happens and where a character goes to think about it, that thinker is sometimes a writer thinking about the thinking about the character thinking. The nowhere where you find yourself in Lorrie Moore’s fiction is the empty space between the spaces of a mirror reflecting another mirror. I am a little sad that the word “meta” is being bled out by purveyors of corporate virtual realities. But writers have long been writing about writing in their writing. You could argue that every story or fiction, whether a realistic narrative or sublime lyric, may be about other things, but they are also always about this this.

__________________________________

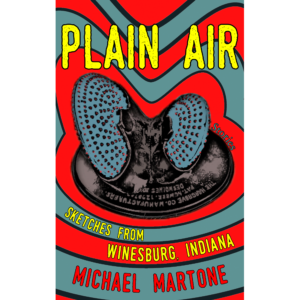

Plain Air: Sketches from Winesburg, Indiana by Michael Martone is available via Baobob Press.

Michael Martone

Michael Martone’s recent books are The Complete Writings of Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, Edited by Michael Martone, The Moon Over Wapakoneta; Brooding. His book Michael Martone is a memoir in contributor’s notes. The University of Georgia Press published his book of essays, The Flatness and Other Landscapes, winner of the AWP Award for Nonfiction, in 2000. With Lex Williford, he edited The Scribner Anthology of Contemporary Short Fiction and The Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Creative Nonfiction. Martone is the author of eight other books of short fiction. His stories and essays have appeared in Harper’s, Esquire, Story, Antaeus, North American Review, Benzene, Epoch, Denver Quarterly, Iowa Review, Third Coast, Shenandoah, Bomb, Story Quarterly, American Short Fiction and other magazines.