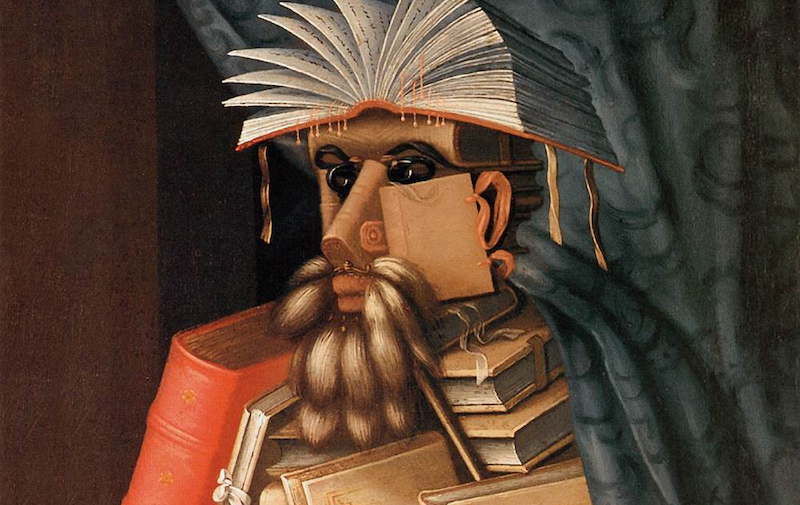

Stories About Stories (About Stories): A Reading List of Meta-Narrators

Eskor David Johnson Recommends Mohsin Hamid, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Lemony Snicket, and More

A meta-narrator has an authorial awareness of a story being told. They make their presence known, intervening when they deem necessary. In the case that they are also the protagonist (which is often) then they must be as adept as immersing themselves in the real-time story unfolding up close as they are in commenting on it from on high.

I have a fascination with these sorts of narrators for as long as I have had stories told to me (which is always). When it came time to approach the task of writing my own novel, Pay As You Go, I knew that I wanted such a narrator at its helm. Slide is as much a participant in the novel’s unpredictable events as he is an intrepid reteller, and is the best companion I could have asked for along the many pages.

To discover him, I first had to do some reflection myself on just how such meta-narrators work, or the differences in their positioning. Here are the results of those reflections.

Patrick Chamoiseau, Texaco

Can storytelling save us? As far as our souls are concerned, sure. But what of actual, existential survival—as a defense against death or erasure? One of our great examples is that of Scheherazade, spinning tales for one thousand and one nights just to stave off a sultan’s cruel judgment. More recently, there’s Chamoiseau’s Texaco, a masterpiece of Caribbean literature.

The novel opens with a modernizing urban planner who is struck by a stone the moment he arrives at the eponymous Martinican slum. Residents are rightly suspicious that he has been sent by some government council to consider the eradication of their shanties.

Unconscious, he is taken unconscious to Marie-Sophie Laborieux, the community’s wisest resident and, of course, our meta-narrator, who recognizes the urgency of relaying the town’s (and townspeople’s) saga, so that the urban planner can see its underlying worth beyond the appearance of some stitched together shacks. What follows is multi-generational saga spanning from the last days of slavery, through decolonization, to the rise of the post-colonial city and the founding of the shantytown Texaco itself.

To make matters more meta, there’s also a stand-in for the author nicknamed Oiseau de Cham, who’s tasked himself with compiling this history through interviews with a now-older Marie-Sophie. Further, the novel is interspersed with excerpts from the urban planner’s notebooks, letters from Oiseau de Cham to Marie-Sophie, pages from Marie-Sophie’s diary and so on. In less deft hands, the whole thing would be unwieldy. Luckily, Chamoiseau and his team of narrators are nothing short of masters.

Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend (trans. Ann Goldstein)

The first book of Ferrante’s four-volume saga begins with the protagonist receiving a phone call. She is old, tried, and soon also annoyed by the content of the call, which is from the son of her erstwhile best friend, and has to do with that friend’s final disappearance. She hangs up, abruptly but reenergized, for the time has finally come to put into words what she has spent her entire life—spanning an impoverished childhood in Naples to bourgeois comforts in Rome—trying to say. “We’ll see who wins this time, I said to myself. I turned on the computer and began to write.”

Thus our story is framed as the final battle after a long contest of wills. Proceeding in mostly chronological fashion from age eight onwards, Ferrante’s novel nonetheless keeps us keenly aware of the older, wiser hand at the helm of proceedings, whose impetus for record-keeping (or setting) permeates the novel. Along the way we become so richly immersed in the characters’ girlhood happenings that we forget the meta-narrator at work, until she interjects to clarify that she may not be remembering something perfectly, or to confess she has skipped over details.

It’s an enjoyable pantomime of weakness that is one of the meta-narrator’s primary indulgences. Nothing would be lost in omitting these interruptions and keeping the story moving along: What difference does a “mis-remembering” make in a fictional story? These self-deprecating interjections on the part of the narrator, like those of an exquisite host apologizing to dinner guests that the soufflé will be a few more minutes, in fact serve mostly to remind us exactly who is running the show—lest we end up forgetting amongst so many delights.

Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children

Saleem Sinai has a problem: he’s falling apart. Not, as he clarifies, metaphorically, but by literal disintegration. In his role as narrator, his time left to tell his tale is dwindling, and the urgency of said telling becomes all the greater for it. It is why Midnight’s Children opens with a conflicted sense of both urgency and reticence, of a narrator who fears he may not get through all that he has to talk about.

Sinai is also another active chronicler, often stepping back from the world of the story to show himself at work at his typewriter under the care of companion and audience stand-in Padma. From here he is free to pontificate, summarize, foreshadow, or bemoan the extent of the labor still left before him. It’s all performance, and begs the question of why he should take the time for detours if there is so much to tell?

But Rushdie couldn’t have chosen a more appropriate guide through the hyperbolic world of newly independent India. In a book that takes on no less a subject than History as its central concern, part of the point of the story is to see it being made.

Mohsin Hamid, The Reluctant Fundamentalist

Hamid set out to write a story with the rhythm of a conversation, that could be read in a single sitting as if having an extended chat. So said so done: in this his first novel we assume the role of interlocutor, addressed directly by a loquacious narrator who tells us his life story. We see him pass from a fresh-faced immigrant to the US, full of bright prospects, to a disillusioned outsider in the aftermath of 9/11 anti-Arab sentiment.

For all the heavy baggage, our narrator seems unflappably upbeat whenever we return to the present moment with him. It is not without intent, and in the novel’s culminating moments Hamid uses his set up to push the story one step further. It seems we were not so innocent in our role as conversation partner after all.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Chronicle of a Death Foretold (trans. Gregory Rabassa)

The true mysteries are those without an answer. Others are mere ploys to lure an audience further along. The question of whodunit, once satisfied, does not encourage us to return again and again to a text, for the author’s primary technique of enticing us though the pages by withholding vital information can be deployed only once before depleting in value. Conversely, questions of whydunit are concerned not with some concealed detail of plot, but rather the unfathomable nature of human desires and intentions, the ones that cause us to love, to cheat, to save and to destroy, which remain infinitely compelling through their essential inscrutability.

As the title suggests, we learn who is to die and by whose hands in the opening sentences, and by the end of the first chapter the deed is done. This is how our meta-narrator frees himself of the mundane concerns of victim and culprit to head onto the mystery that has been haunting him and the townspeople for all the years since: How did everyone let something so avoidable like this happen? There is no satisfactory answer, and the story makes use of its narrator’s reporter-like gaze to revisit the moment, its buildup and aftermath from every possible angle.

What emerges is a tapestry of jilted love, machismo gone awry, a community’s complicity, and the clockwork indifference of fate. Here the storytelling is as self-aware as it is beautiful, and our meta-narrator a necessary cipher through which we are allowed to continually revisit these questions without answers.

Ian McEwan, Atonement

A meta-narrator should never be a mere stylistic quirk; their use should be integral to the story being told. Ian McEwan’s Atonement is a case in point, a novel that would be bereft of its emotional import without its choice in narratorial approach. Reader, here be spoilers.

The book proceeds in seemingly third-person fashion, up to and beyond the story’s major inciting incident: that of a young girl, Briony, mistakenly accusing their estate’s groundsman, Robbie, of sexually assaulting her older sister Cecilia. The consequences are ruinous. We follow the fallout over years of war, estrangement, and heartache, until at the end Cecilia and Robbie finally reunite and see what is left of their unrequited love.

Except this never happens. In actuality, the young Robbie perished in the war, his name still wrongfully sullied, without a chance at redemption. The account we have just read to the contrary has been one of earnest mythmaking on the part of our heretofore hidden narrator: an older Briony.

Haunted by the guilt of her girlhood lie and the damage it caused, she has spent the time since reliving that moment, and rewriting its consequences. It is the fabricated story itself that is the atonement, her attempt to repair through fiction what was rendered irreparable in “real” life.

Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being (trans. Michael Henry Heim)

“It would be senseless,” declares this narrator, “for the author to convince the reader that his characters once actually lived.” Indeed, our narrator here is so meta in relation to the book’s characters—so “above,” to take the words Greek root literally—that we have the sense that he watches proceedings unfold from some divine height. It’s for the best, especially since Kundera is less concerned here with the minutiae of daily experience that is the purview of realism, than he is with the lessons of the sublime made accessible by so lofty a vantage.

We as readers become attuned to the novel’s strange rhythm where the action may be interrupted for an extended musing (in fact, the book opens with two chapters of philosophical reflections before a character is even introduced), or a revisiting of earlier moments in order to re-examine through a new lens. The ambitions of the narrator extend beyond the bounds of simple storytelling and into, as the quote above shows, that of authorship, thinning the divide from Kundera himself.

This peek behind the curtain is in some ways the real show. Kundera’s true power lies in the audacity of emphasizing the wind-up doll nature of his characters, and imbuing them with such a sense of pathos and humanity that we care all the same.

Lemony Snicket, A Series of Unfortunate Events

Reader beware! If you have any other means by which to spend your time, then you should certainly do so instead of reading these books! They are simply too horrible! The story they contain too disastrous, without happy endings!

In similar manner are we warned by our narrator to take every exit available to us instead of continuing to read these episodes. As with any good trick of reverse psychology, it instead has the opposite effect of intriguing us all the more. Snicket is himself a kind of alter ego of the author Daniel Hadler, and assumes his role of both “author” and storyteller with the dire, morbid air of an Edgar Allen Poe creation. He adopts a grandiose pantomime of regret and weariness, forever apologizing to the reader when yet another unpleasant episode must befall the Baudelaire orphans, no matter the ingenious solutions they come up with.

By creating Snicket, Hadler allows his role of author to be assumed by this meta-narrator, freeing himself to be a passenger in this rollicking ride alongside us. All responsibilities are left to Snicket alone, whose shadowy past is slowly revealed to us as the series continues.

______________________________

Pay As You Go by Eskor David Johnson is available via McSweeney’s.

Eskor David Johnson

Eskor David Johnson is a writer from Trinidad and Tobago and the United States. He is the author of Pay As You Go, and his writing has also appeared in BOMB Magazine, and McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern. A graduate of Harvard University and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he was the recipient of the Richard Yates Short Story Prize, the Maytag Fellowship and the Teaching-Writing Fellowship, he currently lives in New York City.