Stop Stereotyping Lexicographers!

John Simpson is an Editor of Dictionaries, and This Is His Story

Ever since I started as a cub lexicographer on the majestic Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in 1976, I’ve tried to pick away at the stereotypes imposed on lexicographers by the media, by the public, and—worse still—by lexicographers themselves. These days, dictionary entries have to be stone-cold sober and analytical, not occasionally spry and whimsical, as they could be in the days of Samuel Johnson (for whom a lexicographer was “a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge, that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words”). And so it’s hardly surprising that the public perception of lexicographers is of a rather dull, plodding crew caught in an endless cycle running from A to Z, and then often turning tail and scampering right back again to the beginning, as we desperately try to capture minor changes from the fringes of language that need to be assessed and defined. And sadly, these stereotypes aren’t wholly wrong. Writing a dictionary is, after all, a serious business.

Many books have been written about the OED, almost all of which concentrate on the tussle between the publishers at the University Press in Oxford and the heroic dictionary editors, or alternatively, between the heroic and long-suffering executives of the publishing house and the awkward, argumentative, and closed-minded lexicographers. That’s mainly because those are the facts that you can extract fairly easily from the archives, depending on which tint you’ve put on your glasses that day. And I suppose there’s something to that side of the narrative.

What the archives don’t contain—and what you have no hope of appreciating unless you come at things from another angle—is the fun and excitement of historical dictionary work. If you need to, step back a few paces and draw a deep breath. This excitement derives equally from the detective work involved, from recovering information which has been lost for maybe hundreds of years (new etymological stories and connections, new first usages, links that you never knew existed between words), and from seeing exactly how words arise out of the culture and society in which they are used. Because words do tell us about the people and cultures that use them.

This is a very specific kind of excitement. It’s different from the knockabout excitement portrayed in Ball of Fire, my favorite film about reference books. I used to play a few minutes of this 1941 screwball comedy to groups of summer-schoolers I taught years ago. I expect they thought it was the best part of the course. In the film, the erudite(-looking) Gary Cooper is the grammarian in a team of gnomelike editors engaged in the noble task of writing an encyclopaedia. The professors have led quiet lives, of the sort that quite unfits them for the vibrant work of reference editing. In particular, they are unfamiliar with the new vocabulary of jive talk and the hepcats. As luck would have it, Gary Cooper stumbles across Barbara Stanwyck (disguised as the nightclub singer “Sugarpuss” O’Shea), and he and his fellow editors take rather a shine to her. They sneak out at night to listen to her vocabulary at a nightclub. Gary Cooper’s article on slang for the encyclopaedia benefits from his entanglement with Sugarpuss, and Sugarpuss is eventually rescued from numerous potential mishaps by the kindly hearted editors. This is not exactly how things worked at the Oxford English Dictionary. Certainly, we never knowingly employed anyone called “Sugarpuss.”

I joined the staff of the Oxford English Dictionary as an editorial assistant in 1976, and I remained with the dictionary for 37 years, until my retirement in 2013. For the last 20 of those years, I was chief editor. From my first days at the OED, I found myself fascinated by the work of creating a dictionary. What captivated me was the English language and its history: how it arose in obscurity 1,500 years ago, and how it grew to define the nations that spoke it. The OED is a historical dictionary: it addresses the whole sweep of English from the earliest times right up to the present day—in Britain, America, wherever it is spoken. And yet we have forgotten so much of our heritage. Every day while I was working on the OED, as a junior editorial assistant or as the chief editor, I could rediscover facts about the English language that had been forgotten for years—just little facts, but ones which need to be remembered to create an accurate picture of English. Or I could write a definition that captured precisely a meaning that had previously only shimmered uncertainly. My colleagues working on etymologies (word derivation) or pronunciations could crack a problem that had confused scholars and researchers for ages past. The lexicographer sees English as a mosaic—consisting of thousands of little details. Each time one of the tiny tiles of the mosaic is cleaned and polished, we see the mosaic more clearly. It’s something of this excitement that I hope to convey in the rest of this book.

The OED is also a descriptive dictionary: it monitors the language, and tells you how language is used, from real-life, documentary evidence. It doesn’t try to tell you—prescriptively—how to use the language. If you don’t like hopefully as a sentence-adverb (“Hopefully, I’ll see you tomorrow”), then the OED will tell you that many writers avoid this usage, but ultimately, it will leave it up to you whether you choose to use it yourself. The dictionary will give you the background: that it arose in the United States in the 1930s—as far as the evidence goes—and has been used steadily since then. And it will tell you that the older meaning (“in a hopeful manner; with a feeling of hope”) dates back to the 17th century. And it will doubtless hope, hopefully, that if you find any better evidence, you’ll send it along to the editors for consideration. I liked the way the OED describes but doesn’t hector.

I didn’t expect to become a lexicographer. I studied English literature at university (York), but I probably spent more time on the various bumpy sports fields of the university than was good for me—as captain and then president of the university hockey team. I certainly did not spend a moment dreaming of a career as a lexicographer. In fact, I’m sure I didn’t know what the word meant.

It was pure chance that I ended up working at the OED, but once I began I never left. I haven’t left now, really—you just don’t. Language continually changes, and every change is a puzzle. The lexicographer is the historical word detective trying to identify and explain these puzzles. If you don’t find the answer now, just set it aside and wait for more information to present itself later. But if you do latch on to a clue, then pursue it until the truth is revealed. The puzzles are inexhaustible, and every answer brings a thrill.

Lexicographers—at least in my opinion—have to come at language sideways. If they don’t, they just see what everyone wants them to see. They need to disbelieve everything they thought they knew about a word and about its context, and start again—building a picture up from the documentary evidence they discover. I found all of this rather bewildering when I first started working on the Oxford English Dictionary, as you’ll see. But gradually I started to gain a more panoramic view of the work and of the language.

Nothing, of course, is perfect. As I continued to work on the dictionary, I—along with many of my colleagues—became more and more aware of cracks in the wallpaper. Back then, the OED was a late 19th-century dictionary which had hardly changed in a hundred years. As editors, we were adding new meanings to it, but really it needed a complete overhaul and update. Would we ever be able to address this monster project? The OED was an intensely scholarly beast, consulted in whispers in university or public libraries. Could we somehow make it more accessible to a wider audience? Oxford itself felt—in those days—very much like an exclusive club, and ordinary people regarded the dictionary as part of this private world, to which they were not invited. Would that ever change? Could we—as dictionary editors—ever help to bring that change about?

The longer I worked on the dictionary, the more I wanted to move the dictionary from being the preserve of the scholar to becoming a modern, dynamic work that kept pace with language. My impression, when I first set foot inside the OED offices, was that the dictionary was dominated by the past. It had a crusty, antiquated air. Where were the real language creators—the mass of English speakers, the everyday poets and writers and conversationalists in whose mouths the language had changed from day to day over the centuries? Could we somehow give them a voice in the OED of the future?

I came to appreciate that there were other ways, too, of opening up pathways into the dictionary. My time at the OED coincided with the great shift from reference works as books to reference works as dynamic, online resources. Oxford was at first slow to notice that the world was changing, and much of this book is about how my colleagues and I put the OED in the forefront of this revolution. Suppose the massive volumes of the Victorian dictionary could be digitized, comprehensively updated, published online, and made searchable in ways that traditional dictionary users had never imagined—we could learn so much more about the language, and about ourselves. And then suppose users could post their own discoveries about the dictionary on an OED wiki and help change the dictionary in the future. The technology was emerging, and immediately we wanted to see how the OED—and its users—might benefit.

The OED is—crucially—a “historical” dictionary: one that observes language historically (language change, language patterns, language growth, the relationship between words and the societies that use them over time) and doesn’t simply look at words from the viewpoint of the definer of contemporary English.

We can be quite confident that we know the meaning of a word only to discover that “our” meaning is the last in a long line of meanings that the word has had over the centuries. The English first encountered to intrigue—according to the OED—back in the early 17th century (the first evidence currently dates from 1612, in the anonymous Trauels of Foure English Men), and the verb meant “to trick or deceive (someone)” or to place them in an embarrassing situation. The dictionary records nine words meaning “to deceive” entering English in the first half of the 17th century (to cog, to nosewipe, etc.). The four Englishmen employed a bit of guesswork in spelling their new word, plumping for intreag. It can take a while for the spelling of a new word to settle down.

From deceit we move on to entanglement. The “learned and reverend” 17th-century clergyman John Scott sagely observed, in his Christian Life (1681), as regards sin: “How doth it perplex and intrigue the whole Course of your Lives, and intangle ye in a labyrinth of Knavish Tricks and Collusions.” In the same passage, Scott noted that we find it very difficult to extricate ourselves from wrongdoing, and he will have known that extricate and intrigue are etymologically close cousins. We understand the sense of entanglement more easily in extricate today than we do in intrigue.

Intrigue entered English as a borrowing from French around 1600. The French themselves only knew it from 1532, when they borrowed the word from Italian (intrigare)—and didn’t give it back, of course. So it wasn’t available in French for borrowing earlier, along with the mass of French words entering English immediately after the Norman Conquest. The Italian word is a late rendering of the classical Latin intricare (parallel to extricare, as in extricate). Latin tricae are trifles, tricks, toys, quirks, or perplexities, as the dictionary dutifully tells us.

To intrigue was on the move in English in the late 17th century. After entanglement came the meaning “to carry on underhand plotting or scheming.” The meanings of the word seem to have intrigued the clergy: Bishop Gilbert Burnet, in his History of the Reformation (1679), reported that (in 1527) “the cardinal of York was not satisfied to be intriguing for the Popedom after his death, but was aspiring to it while he was alive.”

We waited quietly for another two centuries before to intrigue made its next move and became the word we know today: “to excite the curiosity or interest of,” or “to puzzle, fascinate”—in the 1890s. This was another French meaning, though the English did not add it to the semantic arsenal of intrigue until the late 19th century. But we’ve forgotten all that now, and treat all of its meanings as quite English.

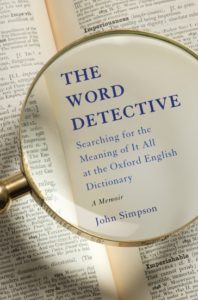

From THE WORD DETECTIVE: Searching for the Meaning of It All at the Oxford English Dictionary by John Simpson. Copyright © 2016 by John Simpson. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

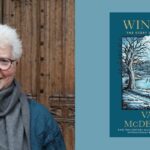

John Simpson

John Simpson is the former chief editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, where he helped take the dictionary online. John is an emeritus fellow of Kellogg College, Oxford, and writes and researches widely on lexical, literary, and historical issues. He now lives in Gloucestershire, United Kingdom.