Stonewall and the Birth of San Francisco's Queer Poetry Scene

Adrian Brooks on the "Bursting Forth" of Queer Poets in California

In 1967, two years before Stonewall and as the Vietnam War fractured the U.S., I was a Quaker boy of 20 in San Francisco for the Summer of Love before joining an international Quaker school. As a student of the Friends World Institute (FWI), a revolutionary college dedicated to creating “agents of social change,” I served as a volunteer for my hero, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., from early 1968 until his assassination. FWI’s main academic requirement was that students keep a journal, while we created individual field programs with faculty advisors. Having started a journal in 1966, one which is now over 8,000 pages and in volume 57, I examined myself by writing in the introspective spirit of Quaker tradition, even while feeling the pulse of the nation at anti-war rallies and at Woodstock.

By January 1970, I was part of the nascent, then-radical SOHO Movement in New York, where I knew art world stars like Andy Warhol. Still, SOHO felt populated by artists on the make, spouting radical pronouncements while buying farms in Bucks Country but as I needed something gutsier: a way to live up to Dr. King’s summons to make every single choice or action of our lives conscious and intentional, I moved to Northern California.

In the early 70s, San Francisco felt like a laboratory for the possible. Still grappling for a feasible identity, I teetered on the edge of coming out completely until, at last, I found a transformative clue in an old journal entry that began by declaring, “I, a poet…”

Writing poetry, and being one of the first in-yer-face gay liberation poets, gave me the gift of my Self—no longer a rudderless lad keeping a journal, but a radical out artist seeing the fusion of the civil rights, anti-war, feminist and LGBT movements into a unified force field. In the face of this realization, all else took a back seat.

Sex hadn’t only come out of the closet; a new language around it went beyond the confessional to the frontal and unapologetic.

In sync with the revolutionary political, San Francisco nurtured and encouraged outsiders to come out and be whoever they were. The vanguard, radical culture in which I found footing welcomed writers into a viable underground that wasn’t about commercial profit but, rather, about community. Magazines such as Gay Sunshine, Manroot (edited by Paul Mariah, who had gone to jail in Texas for making love with his underage lover), and Bastard Angel (edited by Beat poet Harold Norse) first published young writers such as Neeli Cherkovski, Dennis Cooper and myself. This literary movement also included extremely powerful lesbians such as Pat Parker and Judy Grahn. In the heady atmosphere of no-holds-barred liberation, sex hadn’t only come out of the closet; a new language around it went beyond the confessional to the frontal and unapologetic.

What we were doing then was nothing less than setting loose the expression of freedom—a bursting forth of pride—not as arrogant boast but, rather, as the articulation of survival and a determination to declare who we were. Behind us were the brave souls of Stonewall, especially transgender women of color who led the riots, and whom society condemned as the lowest of the low until they’d had enough and fought back against corrupt police bullies fronting for bars, bail bondsmen and Mafia-run businesses that exploited those they jeered at as “queers… perverts… faggots… fairies.”

The fierce fight for basic human rights and pride, so evident at Stonewall, stretched much farther back through the civil rights movement thanks to writers like James Baldwin and Richard Wright. It included feminists, abolitionists and the gay transcendentalists, all of whom had been sanitized, de-sexed and neutered in the officially-sanctioned history of our culture as it was gussied up, written down, documented and squatted on by mainly straight white men who excluded people of color, women, and the transgendered.

Having burst forth, at last—empowered by the righteous rage at Stonewall—a new generation of poets and writers found voice. The civil antique drapery of Mary Renault was replaced by the candor of Patricia Nell Warren’s out-front gay novel, The Front Runner and by Edmund White. Groundbreaking gay Beats like Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Harold Norse were still writing and they’d blasted a way forward, encouraging new voices.

The root of early gay liberation poetry was Uncle Walt’s free-wheeling big voice: the poet as a visionary pantheist allied to Nature and the joyous life force. Drawing on earlier experimental forms like symbolism, cut up, dada, surrealism, automatic writing, and stream of consciousness, poets also benefited from William Carlos Williams’ pared down verse and the breezy Frank O’Hara, who asserted the dynamism of the personal voice liberated from didactic rhetoric and drawing inspiration from direct experience.

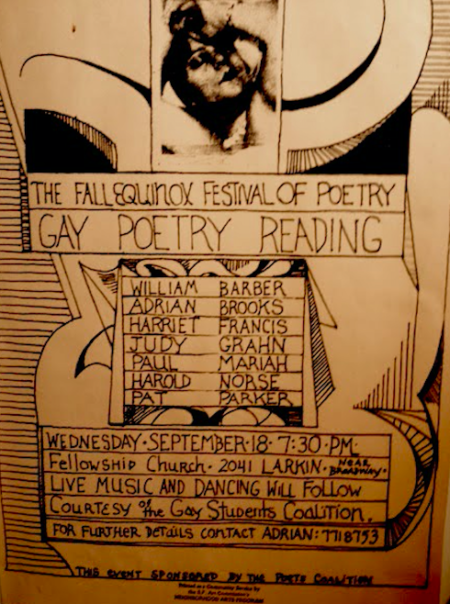

Poster by Victoria Lowe and Max Wolf Valerio

Poster by Victoria Lowe and Max Wolf Valerio

In September 1974, as part of my activism in art galleries and theater, I organized a gay poetry reading at the Fellowship Church. It featured Harold Norse, Judy Grahn, Pat Parker, William Barber, Paul Mariah, Harriet Francis, and myself. Incredible as it may seem now, I’ve been told that it was the first-ever gay poetry reading to be advertised as such. With rare exceptions, American poetry had been in the closet.

On that night, those assembled heard gay men and lesbians issue a crie de coeur. The Stonewall uprising had happened five years before that cool autumn evening, but the ripples of that seminal event were still spreading, and would continue to spread as more and more came forward to declare their pride and dedication to principles set out and codified by Eleanor Roosevelt in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Caught in titanic social change, I was simply a young poet who had trampolined from the quiet soul-searching of introspective journals to the discovery of my Self through words. This discovery would lead me from poetry to my successive roles as a playwright, novelist, and non-fiction writer. But Stonewall reaches beyond any single person’s story. A call to conscience and authenticity lies at the heart of what was then called “gay liberation.” It still is an impetus to justice through words that chainsaw through denial, racism, sexual oppression, patriarchy, and any justification for war.

Adrian Brooks

Adrian Brooks (b. 1947) is a poet and prose writer, an anti-war, civil rights activist and theater artist who has been involved in progressive movements on five continents ever since 1966. He is the author of three novels, two works of non-fiction, a volume of poetry, book reviews or Lambda, interviews, and articles on spirituality. Brooks currently lives in San Francisco.