In a wood, somewhere between Staggia Senese and Poggibonsi, Allied troops were waiting to enter Florence. Dusk was looming, and through the trees came the sound of an accordion stolen from a factory near Trieste.

Standing by his jeep, peering into a broken mirror with the lower half of his face covered in soap, was a young man. He was running the blade carefully across his upper lip, avoiding the scar that had risen two years before.

He had blond hair that revealed a hint of red under the early‑evening sun. No one in the family knew where the red had come from, both sides being dark, and his father often joked that the winter his son was conceived, he’d eaten his fill of beetroot. You were stained, his father liked to tell him.

His features were his mother’s: Straight, slender nose, slightly longer than the required ratio of hairline to bridge, or chin to tip, that would have signified a face in perfect symmetry. Eyebrows at an upward angle conveyed a good listener, and his ears, though not wildly protruding, were definitely alert. When he smiled, which he did often, a dimple appeared in either cheek, which was immediately disarming.

His wife, Peg, said he should’ve been better looking seeing as he’d inherited all his mum’s best bits. She’d meant it as a compliment, but her words danced both ways, hot and cold, kind and cruel, but that was Peg. Unknown to everyone, his apotheosis would come in later years. He would be a fairly handsome middle‑aged man. An eye‑catching elderly man.

The squeal of birds overhead delighted him. He and they had traveled hundreds of miles north against all odds to arrive at that place in time—swifts at the end of March and him in June—and the catalog of near misses and lucky escapes that had accompanied his journey across Africa, Sicily and up the Adriatic would have astonished priests and astrologers alike. Something had been watching over him. Why not a swift?

He looked at his watch and rinsed his face. He threw his pack and rifle into the jeep just as Sergeant Lidlow was coming out of the mess tent.

Where you off to, Temps? Picking up the captain, Sarge.

Bring us back a bottle or two, will you?

Ulysses turned the ignition and the old jeep caught the first time. He drove into the hills, leaving behind the silhouettes of tanks and men. He passed different Allied divisions, young men like him worn old. The soft light moved with him across the groves and meadows, until the sky held only ripples of pink and the night chasing in from the west. He’d tried to practice ambivalence toward this land, but it was futile. Italy astonished him. Captain Darnley had seen to that. They’d traveled up the country together, mostly reconnaissance, but sometimes mere wandering. Through remote villages, seeking out frescoes and hilltop chapels.

Peg said he should’ve been better looking seeing as he’d inherited all his mum’s best bits; her words danced both ways, hot and cold, kind and cruel.

A little over a month before, they’d driven up to Orvieto, a city built on a huge rock overlooking the Paglia valley. They’d sat on the bonnet of the jeep and drunk red wine out of their canteens as bombers roared overhead toward Mount Cetona, the boundary of Tuscany. They’d stumbled into the cathedral, into the San Brizio Chapel, where Luca Signorelli’s masterpiece, the Last Judgment, could be found. Though neither of them was a believer, the images had still held them to account.

Darnley said that Sigmund Freud had visited in 1899 and had somehow forgotten Signorelli’s name. This he’d called the mechanism of repression and it became fundamental in Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. God—but you probably know this already, don’t you, Temps? And not waiting for an answer, Darnley marched out into the crisp June sun, leaving Ulysses giddy in the whirl of information, and in Darnley’s unwavering belief in him.

The road straightened out and from the trees in the distance, a glint of light flickered across his face. He slowed and came to a stop with the engine running. He reached down for his binoculars and saw it was a woman standing by the roadside watching him through hers.

She waved him down with an unlit cigarette, and when the jeep came to a halt, she cried, Oh thank God! Eighth Army?

Just a tiny fraction of it, I’m afraid, said Ulysses, and she held out her hand.

I’m Evelyn Skinner.

Private Temper, said Ulysses. Where’ve you come from, Miss Skinner, if you don’t mind me asking?

Rome, she said. What? Now?

Good Lord, no! From that albergo behind the trees. Came up a week ago with a friend and stopped off in Cortona to assess the damage to the Francesco di Giorgio. Miraculously untouched. We’ve been waiting ever since.

Waiting for what?

I’m trying to contact the Allied Military Government. For what purpose, Miss Skinner?

To liaise with the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives officers. They know I’m here, but they seem to have abandoned me. I’m an art historian. I thought I could be of use once they’ve located all the works from the museums and churches. They’ve been sequestered around these hills, you know. All the masterpieces. The whole gang—even dear old Cimabue. But I suppose you know that, don’t you?

Ulysses smiled. I did hear a rumor, Miss Skinner. Do you have a light? she asked.

I wouldn’t recommend it. Look what happened to me. And he pointed to the scar at the corner of his lip. Sniper, he said. A near miss.

Evelyn stared at him. But it hit you, she said.

But not the important bit, he said, tapping his head. Nearly took my lips off, though. Then where would you be?

Struggling with my plosives, Private Temper. Now, light me up.

Please.

Ulysses leaned across and struck a match.

Thank you, she said, blowing out smoke in a perfect circle. She raised her arm and looked about. See? No snipers. So, do you think you can help me? I’ll be no trouble at all. And my lips, still perfectly intact, will be forever sealed. What do you say?

You’re putting me in a bit of a bind, miss. Oh, I’m sure you’re no stranger to that.

Do you believe in fate, Miss Skinner?

Fate? It is a gift. According to Dante, anyhow.

A gift? I like that. Come on then, miss, hop in.

Oh, drop the “miss,” for God’s sake, said Evelyn, sitting down next to him. My name’s Evelyn. And yours?

Ulysses.

Ulysses! How wonderful! And is there a Penelope waiting for your return?

Nah. Just a Peggy. And I doubt she’s waiting. And he turned the ignition and the jeep pulled away.

The rogue shelling that had accompanied the afternoon had ceased and a soft, almost believable, peace lay across the wooded hills and hilltop refuges, across the dark symmetry of vines that terraced the slopes.

Ulysses lit a cigarette.

So, said Evelyn, tell me a little—

London. Twenty‑four. Married. No kids.

Evelyn laughed. You’ve done this before.

You gotta be quick, right? Could be dead tomorrow. You?

Kent. Sixty‑four. Unmarried. Childless. And what of life before all this?

Globes, he said. Dad made ’em and I sold ’em. Then he died and I just made ’em.

You made the world turn!

Find a Temper & Son globe and you’ll find my mum’s name hidden somewhere on the surface.

A town called . . . ? she asked. Nora.

How romantic. Nice, right?

You and Peggy like that?

Nah, me and Peg are the opposite. Left to me, I’d name stars after her. We got married on a bender, only way we could do it. When she woke up and saw the ring, she punched me in the face. Happiest day of my life, though. Then I joined the army and we’re strangers again.

Don’t you write to one another?

He shook his head. We know what we’re both up to, he said. Thing is, it’s always been us when the others have left. Always that spark when the lights have gone out. Is that love?

Oh, don’t look at me. I’ve not stayed long on that particular horse. Never?

Once or twice, maybe.

Once is enough. We just need to know what the heart’s capable of, Evelyn.

And do you know what it’s capable of? I do. Grace and fury.

Evelyn smiled, and drew heavily on her cigarette.

So that—and she pointed to his lip—was Peg and not a sniper.

No, that was definitely a sniper. Look, he said, and he raised his right arm and showed the scar along his wrist. Shrapnel, he said.

He leaned toward her and parted his hair. Sniper, he said. He pulled up his trouser leg. Evelyn winced. Artillery fire. That one got infected. And then this. And he unbuttoned his shirt.

Good Lord, said Evelyn. Another near miss? A lucky escape, he said. There’s a difference. How so?

It’s all mental. How I see life at that time. This last one was in Tri‑ este, and there’s been nothing since. And now I know I’m not going to die. And I’m a lot happier.

Excuse me? said Evelyn. Not die here, I mean.

Italy here?

War here, he said. It’s like having a debt hanging over you. You know it’ll be called in, but it’s how it’s gonna get called in that’s the question. What I mean is, all those opportunities to kill me off. I’m still here. There’s a reason for that.

Poor aim might be one, said Evelyn. You’re funny, Evelyn.

And you’re a very optimistic young man.

I am, he said, I’m glad you noticed that. And he went on to explain that his optimism came from his father, Wilbur, whose wise counsel of “Life’s what you make it, son,” had been firmly entrenched in him from a young age. The man was a dreamer, he said. Had a loser’s luck and a winning smile and was never happy unless he had a churn in his guts that denoted money riding on an outcome. A feeling he often equated with love.

The man was a dreamer, he said. Had a loser’s luck and a winning smile and was never happy unless he had a churn in his guts that denoted money riding on an outcome.

But then one day it happened for real. He walked into the pub, stood on a table and declared he’d fallen head over heels and everyone thought she’d be some tidy young thing, but she wasn’t. She was almost as old as him, slipping down the other side of fifty. Tired, kind face with the keenest blue eyes that looked at him as if he was a meadow of wildflowers. And two months later—against all odds—she told him they were having a child, a first for both.

The most beautiful words in the world, said Ulysses. Having a child? said Evelyn.

Against. All. Odds.

This recognition of double luck—wife, and kid incubating—brought back a familiar taste to Wilbur Temper, like sucking on a coin.

And his palms are tingling, said Ulysses, the soles of his feet too, and he knows this feeling because it’s a winning feeling and you can never let a winning feeling pass because that would go against nature. So, he goes to my mum and explains what he needs to do. Last time, she says. Last time, he promises.

Now, his mate Cressy has told him about this illegal greyhound meeting out in Essex, all hush‑hush and big money, and they go out there together and study form and he scribbles in his notebook a beautiful constellation of numbers, subtractions, additions, an algebraic formula of luck. Last race. Everything on the black. That’s what he used to say. All or nothing. And he places life and savings on a tan and white dog called Ulysses’s Boy at a hundred to one.

The rest is folklore. Dog came in first, thus ensuring two things: enough money to set up a modest business in handmade globes, and a memorable name for his sole son and heir.

You were named after a greyhound? said Evelyn.

A winning greyhound, Evelyn. Winning.

The heavy presence of artillery guns and infantry came into sight long before the villa. At the checkpoint, they were waved on through. Along the driveway they could see military guards and Italian civilians placing Off Limits signs at every entrance to the ornate building. Captain Darnley was waiting for them outside. He was wiping his glasses on the tail of his shirt. He looked up, squinting at the sound of the jeep. His dark hair had a premature dusting of gray at the sides that made him appear older than his thirty years, and his dark eyes peered out from dark sockets and gave him a perpetual look of sorrow. Rather like the last panda facing extinction. He put his glasses back on and approached the jeep.

Temps! he called. Temps!

Ulysses parked the jeep and got out. What’s up, sir? he said.

We found a cellar. Jerry must have missed it. We’ve been drinking all bloody day. I think I’ve drunk myself sober.

Not yet you haven’t, sir. Sir, this is Miss Evelyn Skinner. Miss Skinner, Captain Darnley.

They shook hands. A pleasure, Miss Skinner, said Darnley. Likewise, Captain, said Evelyn.

Miss Skinner’s an art historian, said Ulysses. She’s been trying to contact the Monuments officers through the AMG. I thought there was a good chance they’d be here, sir.

Not yet they’re not, Temps, said Darnley. But fear not, Miss Skinner, we shall get you your contact. But first, follow me. Come on, Temps, you too.

He led them toward the villa and said, It’s quite a haul. Only uncovered 24 hours ago.

And as they crossed the courtyard and passed the guards, Evelyn said, Are you saying what I think you’re saying, Captain Darnley?

In here, said Darnley, and he pushed open the large wooden Baroque doors into the salone. The stink assaulted them.

Oh my word! said Evelyn, covering her nose.

Sorry, Miss Skinner, said Darnley, I should’ve warned you. The Germans like to shit everywhere before they retreat. Watch your step. It’s quite a sewer in here.

It was hard to see anything except for the dark shapes of furniture. The shutters were drawn, and the air was lifeless, and the flies were giddy. Underfoot the sound of broken glass and broken tiles, and brick dust swirled. Wait here, said Darnley as he went across the room to a lamp. He bent down, struck a match, and raised the lamp with a theatrical flourish. The room flared with light, and in the middle, rising out of the stink and gloom, was a large undamaged altar panel.

Oh my, whispered Evelyn.

Ulysses Temper, Miss Evelyn Skinner, I’d like you to meet Pontormo’s Deposition from the Cross.

Do you think they’d let us take it now, Captain Darnley, and save them the trouble? asked Evelyn.

Darnley laughed and said, Shall we ask? What is it exactly, sir?

One of the great altarpieces portraying the life of Christ, Temps.

Isn’t that right, Miss Skinner?

You are correct, Captain. Painted to hang above the altar in the Capponi Chapel in the church of Santa Felicità. Completed in 1528. Give or take. The style is what we would call early Mannerist, Ulysses—a break in tradition, that’s all—away from High Renaissance classicism and everything associated with it. You can see it’s a deliberate denial of realistic style, calculated, and artificial. The light—you see—theatrical.

And she went on to explain the difference between a deposition and an entombment. The dreamlike use of color, the sparseness of the image, the dance.

She said, It’s about feeling, Ulysses, that’s all. People trying to make sense of something they can’t make sense of.

(The faint sound of laughter trespassed on the room.)

It’s simply the dead body of a young man being presented to his mother, said Darnley.

Oldest story in the world, said Evelyn. Which is?

Grief, Temps. Just a lot of fucking grief.

They ventured into the further reaches of the villa. Military guards and Italian custodians marched past, carrying religious relics and statuary. They stood back as Filippo Lippi’s Annunciation was maneuvered through as if it was a deck chair.

Darnley stopped outside a small wooden door. Here we are, he said.

Worst‑kept secret in Tuscany. Shall we?

Candles threw scant light onto the edges of the stairwell. There was a strong smell of damp stone and tallow, and the level of oxygen thinned as they made their descent. The staircase eventually leveled out into a vast cellar lit by oil lamps. The floor appeared bloodied where dozens of oak casks had met their fate. Documents and books lay scattered and the ceiling was propped up by timber. A pathway had been cleared through the rubble toward a wall of shelving, which was, in fact, a magnificent trompe l’oeil. As they got closer, Ulysses could see the incongruous seam of a door.

Abracadabra, said Darnley.

How many more white rabbits can we expect, Captain? Hat’s empty now, Miss Skinner. After you. Please.

Darnley opened the door and conversation and music spilled out. The room was a long narrow corridor, Caravaggesque shadows in the corners where the throw of candlelight was simply too weak to penetrate. Broken glass littered the floor and two plundered walls of wine disappeared into the furthest reaches. Smoke hovered above tables occupied by Allied officers and Italian superintendents and the only air came from a grille in the ceiling, where the fug was sucked out in sporadic gasps.

What’ll it be, Miss Skinner? Something red? Surprise me, said Evelyn.

Darnley went to the rack, flexed his fingers and reached for a bottle.

He looked down at the label and gave a thumbs‑up.

A 1902 Carruades de Lafite. Pauillac! he shouted. Heavenly! (A word he used a lot, which was odd for a man whose idea of the afterlife was oblivion.)

They sat down at an empty table and a private emerged out of the shadows carrying three crystal goblets, a corkscrew and a small plate of thinly cut pecorino cheese.

You see, Miss Skinner. It’s really not much different from the Garrick.

Evelyn laughed.

Darnley did the honors. A neat little pop, the smell of the cork and the comforting glug of the pour.

To what shall we toast? said Darnley. What do you think, Temps? To this moment, sir.

Oh, very good, said Evelyn.

To this moment.

_______________________________________

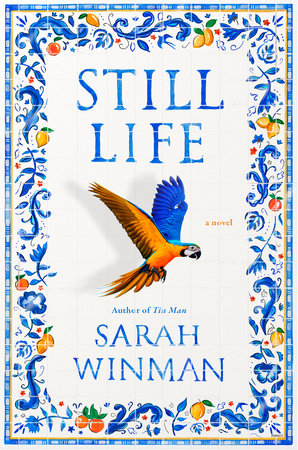

Excerpted from Still Life by Sarah Winman. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, G. P. Putnam’s Sons. Copyright © 2021 by Sarah Winman.