Still Fighting For Liberty and Justice For All: A Visual History of Black America

LaGarrett King on the Invaluable Contributions of Black Revolutionaries to America’s Founding

The phrase “founding fathers,” first coined by Senator Warren Harding, referred to the men who framed and adopted the documents that shaped the United States. These statesmen and politicians attended the Continental Congresses, signed the Declaration of Independence, participated in the American Revolution, and wrote and signed the Constitution.

However, the concept of founding fathers gives short shrift to all the other persons who built the nation: the poor, migrants, soldiers, women, Native Americans, and Black people who have shaped what became the United States of America that we know today. Just as critical to our nation’s formation were Black Founders, who set a precedent for freedom for Black Americans and consequently for all Americans across our shared history.

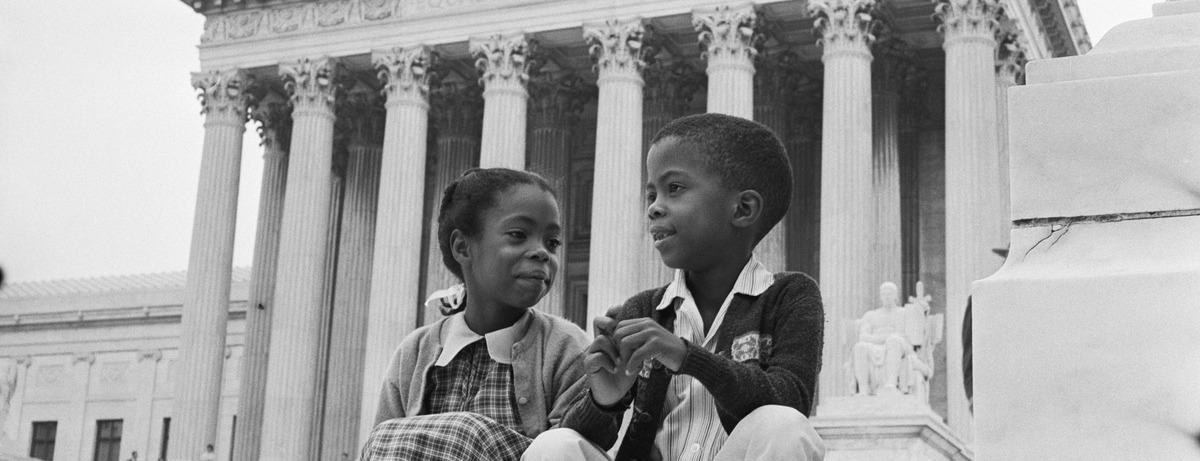

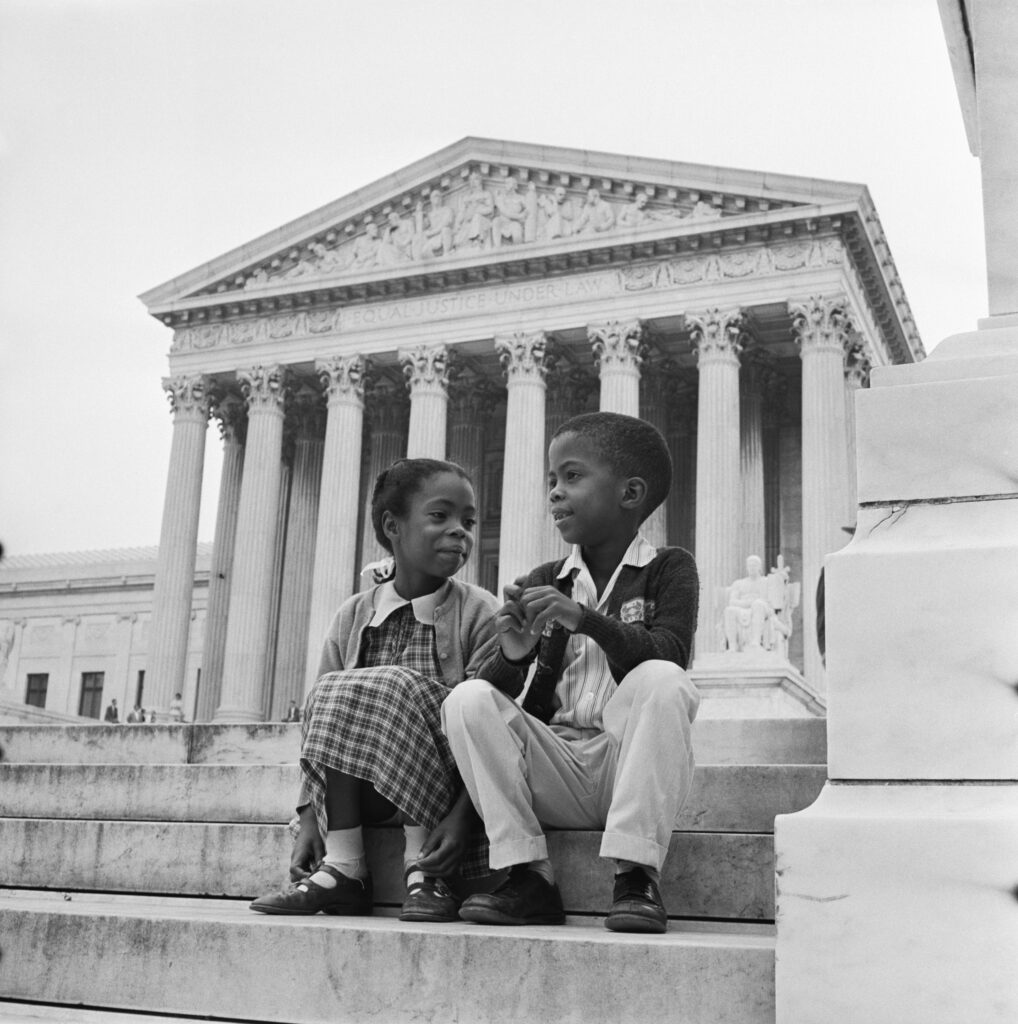

Children sit in front of the Supreme Court which is hearing arguments about the integration Little Rock Schools. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

Children sit in front of the Supreme Court which is hearing arguments about the integration Little Rock Schools. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

Who Are Black Founders?

Black Founders were men and women of African ancestry who lived during colonial times. Their ideas and actions helped form economic systems, win freedom from the British, establish social institutions, and fight racial prejudice in the emerging United States.

Black Founders did not necessarily hold the same philosophical principles as their white counterparts, and in many cases their ideas and practices contradicted white Founders’ beliefs about race and democracy. Given their racist exclusion from the larger American society, Black Founders were more concerned about building a country within a country—one for Black people.

We can classify Black Founders into four groups: the enslaved; revolutionary soldiers; institution builders; and race leaders.

The Enslaved

Enslaved Black people’s labor developed the nation’s economy. These people sacrificed a great deal for the United States and helped make it a global economic power.

Black Founders…understood that the country founded on the principle of equality was, in fact, deeply racist and did not apply that principle to all.

U.S. enslavement yielded considerable profits from cotton, sugar, tobacco, and rice crops. Enslaved Black people also built the infrastructure of this country, including constructing Washington, DC, the nation’s capital. And they created their own culture, mixing the practices of various African cultural groups, like the way that African foodways influenced Southern cuisine, which continues to shape American life today.

The Black Revolutionary Soldier

Black persons were instrumental in the American Revolution as soldiers, guides, messengers, and spies. Their presence as soldiers was significant for several reasons.

Their actions repudiated the racist ideas that Black people were not brave or capable of military service. Their presence in arms demonstrated physical strength and required a certain mental capability.

Their military participation also complicated the idea of patriotism—Black soldiers were patriots in the conventional sense of the term. Black revolutionary soldiers were fighting for freedom, not for the thirteen colonies but for themselves individually and for the race as a whole.

Pictured above: A horse drawn carriage carrying the body of civil rights icon, former US Rep. John Lewis (D-GA) crosses the Edmund Pettus Bridge as it prepares to pass members of his family on July 26, 2020 in Selma, Alabama. On the second of six days of ceremonies, Lewis’s funeral procession continues to follow the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail on its way to the State Capitol where he will lie in state. On March 7, 1965 Lewis and other civil rights leaders were attacked by Alabama State Police while marching across the bridge in support of voting rights for African Americans. The day would come to be known as “Bloody Sunday.” (Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images)

_______________________________________________

For Black revolutionary soldiers, freedom and liberty carried very different meanings than they did for their white comrades. Black American revolutionary soldiers were fighting the “African Americans’ Revolution,” a separate cause from their white counterparts.

Social Institutions

Black Founders established social institutions for Black life throughout the late 1700s and early 1800s, including religious, social, political, and economic institutions. These places served as safe spaces, allowing Black people to be among their kind without fear of racism.

Some examples of these institutions include the African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones and which traces its roots back to 1787, the very year the Constitution was drafted; the Freedom’s Journal, edited by Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwurm and first published in 1827; and the African Masonic Lodge established by Prince Hall in 1784. Black women, too, founded their own organizations, such as the African Female Benevolent Societies.

Pictured above: Students at mostly Howard University vowed to continue their rebellion until radical changes are made in the federally supported university’s administration. The university was shut down on March 20th when the demonstrators occupied its administration building in the center of the school’s campus. School officials, locked out of their own offices, appeared to be waiting out the students’ protest in hopes the 2-day protest would fizzle. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

_______________________________________________

Race Leaders and Critical Intellectual Agency

The fourth category of Black Founders comprised race leaders who promoted what I have termed critical intellectual agency—how Black Founders challenged the philosophical, social, and moral underpinnings of United States’ alleged egalitarianism. Critical intellectual agency was an intellectual space for Black Founders to promote racial justice and repudiate white Founders’ views about Black Americans and race.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Black Founders wrote speeches, pamphlets, and newspaper articles about their rights to full citizenship, cleverly and sometimes subversively using the same ideas promoted by white Founders. According to the Black Antislavery Writings Project, more than 1,500 documents were written by Black people about their rights to freedom and ideas about race. Persons such as David Walker, Daniel Coker, and Phillis Wheatley promoted racial justice and contradicted the era’s prevailing racial “theories.”

Benjamin Banneker’s letter to Thomas Jefferson, written on August 19, 1791, articulates a view of race that stood in opposition to the prevailing one of the times. Banneker—a scientist, inventor, and astronomer—was best known for his contribution to surveying Washington, DC, and for his almanacs. His 1792 almanac contained a rebuttal letter to then Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson about his writings on race. Jefferson wrote about his conflict with race, stating that the institution of slavery was evil, but he also wrote that Black people were naturally inferior to white people.

Pictured above: People play double dutch during a Juneteenth celebration in Fort Greene Park on June 19, 2022 in the Brooklyn borough of New York City. President Biden made Juneteenth a federal holiday in June 2021, proclaiming it as a day for all Americans to commemorate the end of slavery. The date’s history goes back to the year 1865 when Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas to deliver the news that slavery had ended after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. (Photo by Stephanie Keith/Getty Images)

_______________________________________________

Banneker challenged Jefferson to rescind his proslavery stance, support abolition, and reevaluate his thoughts about Black people’s intellectual capacities. He chastised Jefferson’s moral authority as well. Banneker’s letter became a commentary on the egregious racialization in America and established the antecedent for antislavery advocacy.

Black Founders such as Banneker set a precedent for social justice. They understood that the country founded on the principle of equality was, in fact, deeply racist and did not apply that principle to all. They attempted to fix that error. They challenged white Founders’ misguided racial prejudices and made their voices heard. Black Founders established what we can think of as a separate nation within a nation, and in so doing they were uniquely American.

__________________________________

From Picturing Black History: Photographs and Stories that Changed the World by Nicholas B. Breyfogle, Steven Conn, Daniela Edmeier and Damarius Johnson. Copyright © 2024. Published by Abrams Books. Text © 2024 Ohio State University.

LaGarrett King

Dr. LaGarrett King is an associate professor of social studies education at the University of Missouri. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin after an eight-year teaching career in Georgia and Texas. His primary research interest examines how Black history is interpreted and taught in schools and society. He also researches critical theories of race, teacher education, and curriculum history.