Stephanie Powell Watts: Maybe the Next Move Will Change Our Lives?

On a Childhood of Constant Relocation

When I was a kid we moved around a lot. We didn’t always move out of town and never out of the state of North Carolina, and often our move was just a few streets or neighborhoods over from where we started. I can’t remember the first time we moved when I knew for sure it would only be temporary, that there would always be another pack-up, another move—a few months, maybe a year at the most down the line.

I do, however, remember our first move. After my parents’ divorce, my mother, two of my four brothers, and I left our dirt road for a house in the next small town. The house was old though not charmingly so, definitely in before condition, and surrounded by many other tiny, rundown houses. It wasn’t all bad, though. Even now, more than 30 years later, I think of the to-the-ceiling white kitchen cabinets and the phone niche in the hallway with some fondness. For the few months we lived there, we stumbled over boxes, trash bags of clothes, toys, and miscellaneous junk hastily piled anywhere there was space. We did not stay at this house long enough to fully unpack.

I remember being so excited. I know this is hard to believe, but moving was a great adventure. Life was different then. The people we knew were skinny and poor and drove around in dogs of cars and counted out money from their piggy banks at the end of the month for gas. We did not travel. We knew nothing of the world. We marveled at the middle-aged white people we knew from school or work that had been to Paris, France, and London, England, and could prove it with slides. We didn’t have disposable income—that wasn’t even a phrase we knew yet—and everyone we knew lived frugally by necessity. I remember my mother and a friend talking about another friend who was having such hard times she had to use a credit card at the grocery store! I’ve thought of their conversation many times when I’m paying for bananas and a carton of milk with my Visa.

My mother was convinced and convincing, and every time she felt the need, she sold us on the idea that this next move would change our lives. She believed in the power of place as the springboard for our reinvention. Anything was possible this time. The slate of our existence would be wiped clean and we would get to rethink and redo everything. I caught her enthusiasm. I loved the anticipation of the move, the process of going through our possessions and deciding what was worthy enough to make the trip to a new life. Those too baggy shorts, toss; the once-loved blouse with the impossible stain, out. We had to travel light. We had room only for the good. My mother’s motto could have been, “Change your address and change your life. This time we are going to get everything just right.”

“Mothers all over the country and from every walk of life, like my mom, scrape together every penny they have, set their sights on a new place, and start over.“

I have since learned that a good number of poor women with their children move with regularity. But at the time, when I was young, I knew of only one other kid who moved around like I did. She had come from a big city and told me in one of our true confession sessions that her mother could not stay put. The last move my friend made in childhood had been to North Carolina when her mother left her in the care of her grandmother and had not returned. I learned then the power of a secret to seal a relationship. Tell me a secret and I give you my trust. I had imagined all that time that I was the only one coming to school red-eyed and exhausted after spending most of the night unpacking boxes. But I have learned as a grown person that there is no malady, or pathology in this wide world that someone else isn’t suffering right along with you.

Mothers all over the country and from every walk of life, like my mom, scrape together every penny they have, set their sights on a new place, and start over. I get it. The urge for change, any life-altering change, is strong. The desperate need for control of anything at all is even stronger. Moving is kinetic and purposeful at just a time when the world seems most out of control. The mind needs diversion from constant trouble and grows weary from weariness, tired from constant fatigue. The mind can focus only so long on lack or pain or loneliness, and needs a persistent and consuming outlet that feels necessary. Pack everything you own, stuff the kids in the car. Find the right house or apartment and find the right life.

I have been thinking a lot about moving since my family bought a new house (new to me) in Allentown, Pennsylvania. My young child did not want the change. I love our home, mama, I don’t want to leave. The old feeling of excitement and dread and the thrill of maybe this time that I thought I’d buried too deep to access welled up, but now I was the pleading mama. “You will love it, honey. We will be near a park. Your room will be so beautiful. Everything will be just like you want it.” It wasn’t just talk. I was willing happiness into being, insisting on it. I would not tell my sweet son that being on the move made me feel like an outsider, but like a seeker too. I still worry that in the rest and the nesting that the seeker discovers that no room can ever truly fit, no apartment, no house has space enough for the seeker’s great and consuming needs.

I have not lived with my mother for more than a generation now. It has been a long time since I’ve felt her enthusiasm sweeping me all along to the next house and the next bright future. Somehow even after all this time, I feel the tickle of desire every two or three years to pack the car, leave the broken and unloved detritus behind, travel two streets or two towns over, and start again. Everybody in the car together.

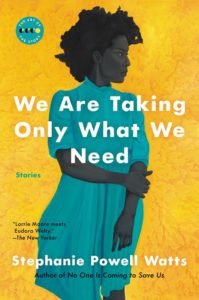

The stories in my collection are about young African American women trying to find their homes in the world. The stories are set in North Carolina in the new south, post-segregation, post-Jim Crow, post-lawful separation of races, but those ghosts endure. My characters are usually poor, but not content to be so. They are usually watchers, but at crucial moments are compelled to act. They are girls determined to be proud women. The world has a place for them and they will find it. And some of them will find that place that can finally feel like home.

__________________________________ From the introduction to We Are Taking Only What We Need. Used with permission of Ecco. Copyright © 2018 by Stephanie Powell Watts

From the introduction to We Are Taking Only What We Need. Used with permission of Ecco. Copyright © 2018 by Stephanie Powell Watts

Stephanie Powell Watts

Stephanie Powell Watts is an associate professor of English at Lehigh University, and has won numerous awards, including a Whiting Award, a Pushcart Prize, the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence, and the Southern Women’s Writers Award for Emerging Writer of the Year. She was also a PEN/Hemingway finalist for her short-story collection We Are Taking Only What We Need.