Standing Tall: On the Value and Importance of Women Who Take Up Space

Jane Smiley in Conversation with Susan Swan, Author of “Big Girls Don’t Cry”

Is our size a psychological influence in our lives like other markers such as race, class, cultural background and gender identity? In this conversation, six-foot-two author Jane Smiley (A Thousand Acres, Moo and Lucky) compares notes with her friend and counterpoint, six-foot-two novelist Susan Swan, author of the new memoir Big Girls Don’t Cry about the way Swan’s Amazonian size shaped her life.

*

Jane Smiley: I think the great pleasure of your book is that it makes you understand what it feels like to exist—to come to terms with who you are, how your body works, what you look like to others, and how that shapes you. Why did you write a memoir about your height?

Susan Swan: I had no intention of writing Big Girls Don’t Cry. Margaret Atwood, who’s a friend, suggested it. I wrote it off as a goofy idea but the more I thought about it, the more I realized my Amazonian size has shaped my life. For many of us, our size is how we pattern ourselves, and its influence affects us psychologically along with other markers like our class and cultural background, our race and our gender identity. This is especially true for women whose bodies are constantly scrutinized and judged in a way men’s bodies aren’t. To be a tall woman is to be a big woman, and to be big is to take up space, a cultural no-no for women of all sizes who are taught early on to cede space while men are encouraged to take up as much room as possible. God forbid, I might get bigger, I told myself when I hit six-foot-two at twelve.

To be a tall woman is to be a big woman, and to be big is to take up space, a cultural no-no for women of all sizes who are taught early on to cede space.

JS: At six foot two, you and I are in the 99th percentile of women in most Western countries. How did you feel about your body as a girl?

SS: When I grew up in the late 1950s and early 1960s children laughed at me on the street, and a boy burst into tears when he drew me on a blind date. Another teenage boy suggested I should get four inches cut off my thigh bones, so I didn’t have to join the circus like Anna Swan, the Victorian giantess who exhibited with P.T Barnum in New York. Interestingly, when I was a reporter in my twenties, I interviewed a formerly six-foot-one woman who had that very operation in the 1960s because she was so traumatized by her height. The Toronto surgeon who performed the surgery said he did it as act of compassion. No medical doctor would say something like that now about a tall woman.

But don’t forget in those days the Guinness Book of World Records defined a giantess as a woman six-foot-two and over. In the 1958 Hollywood movie, Attack of the Fifty Foot Woman, a giantess played by Allison Hayes squashed men like bugs until the town sheriff killed her. The movie was a metaphor for men’s fear of big women and that subtext wasn’t lost on me. Mothers used to say, isn’t it too bad you’re so tall when you’re a girl. Did you have those reactions when you hit six foot two by the age of fourteen?

JS: Not really. For one thing, I didn’t have to put up with teasing. My mother did take me to some doctor with the idea of shortening me, but the procedure sounded so painful that I refused. I also thought that my hands would be down by my ankles if they shortened my legs, and so I would look even weirder. I kept me eye on Verushka (a model) and Vanessa Redgrave (an actress), and I thought there was something independent and graceful about both of them. My mother spent years as the Women’s Page editor of a St. Louis newspaper, so she had her eye on the models, too. She even took me to someone to see if I could be a model, but whoever it was said that my hips were too narrow. But my two real passions were reading and horseback riding, and both of those had nothing to do with height.

SS: It sounds like your mother was more worried about your height than you were. And you didn’t have a giantess lurking in your family background like I did. I was deeply affected by Anna Swan’s story. She was my childhood bogey woman because she stood seven-foot-six in her stocking feet and weighed 418 pounds which is why Barnum billed her as The Biggest Modern Woman of the World. After she left Barnum’s American Museum on Broadway, Anna and her husband the Kentucky Giant, Martin Van Buren Bates, travelled with American circuses. Anna looked attractive in her photos. She was said to be intelligent and enjoyed books and learning.

Nevertheless, I was terrified I would grow up to be too tall like her. My country doctor father and his medical texts didn’t help either. I used to sneak looks at them when nobody was around. As a child, I was horrified by the naked photographs of women and men who suffered from genetic disorders that to my kid’s mind made them look like ogres in a gothic fairy tale. There were several pictures of people suffering from gigantism, a defect that makes the pituitary gland produce excess growth hormone. Sometimes the hormone also causes their bones to thicken.

JS: Are you related to Anna Swan?

SS: I’ve researched my ancestry several times, but no family connection has come up. While I was writing a novel about her life, I did interview Anna’s descendants, and they had interesting stories to tell about Anna sitting on the floor, so her head was level with her siblings when they ate their meals of crowdie or porridge. They were poor farmers. But the Nova Scotian Swans are short people who had no connection to my branch of the Swans who are tall except that our families both come from Scotland. Experts say now that Anna likely suffered the effects of an excess growth hormone from her pituitary gland.

JS: You grew up in a small Presbyterian town in Canada where social rules, especially for women, were very strict. Is that why your book uses the metaphor of breaking out of boxes that held you back?

SS: Most of us grow up inside political and psychological frameworks that can restrict and confine us instead of helping us grow into our best selves. A conservative, rule bound Fifties culture like the one that socialized me had lots of restrictive boxes, the Go Along Box, the Traditional Female Box, the Spinster Box, the Dutiful Daughter Box. You get the idea. Canadian culture then was concerned with appearances and not blotting your copy book, as the expression went.

JS: You were young during the 1970s second wave of feminism and the constraints women faced then. Why did you say some forms of feminism can become another box?

SS: I wouldn’t be anywhere, and neither would you without feminism and its support of women’s rights which are being severely challenged right now in the US. What I’m saying in my memoir is that feminist moralizing can turn into a box if the ideology becomes too narrow and rigid. In the 1970s, women who publicly admitted to liking and desiring men were sometimes dismissed as lipstick feminists even though they, too, were rebelling against the patriarchal attitudes and behaviour that hurt women. So, two of my friends in the performance art scene and I started exchanging diaries by snail mail to talk about our obsession with men and our sexuality.

A screenplay I wrote then based on the diaries was called A Treatise on Ethics: It’s Not All Porn. While exchanging our diaries, we concocted a revenge mission we referred to as The Assignments. The idea was to punish predatory men by seducing them and then humiliating them. We each did one assignment and that produced sad, comic and unfortunate outcomes, so we dropped the project. We ended up feeling petty and mean, and our mission didn’t change the political situation women like us faced. I get the sense that you had fewer boxes to break out of growing up in St. Louis. Was that the case?

JS: There was something about St. Louis, at least where I grew up, that was easygoing and accepting, maybe as a result of all of the cultures that developed there because of its position, more or less, where the south, north, east, and west come together. My family was non-judgmental. But I also think I would have been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder if they had had that diagnosis at the time. One of my early report cards—I think fourth grade—said, “She only does what she wants to do.” I wandered around our neighborhood, was very curious, and I felt safe. As I got taller, I felt sorry for the shorter girls, because I thought maybe they were in more danger. I think that I attributed my failure to attract a boyfriend to my glasses, my mouth-breathing, and the fact that I was skinny as a rail. But that was okay with me, because I was more interested in books and horses.

SS: I also felt safer and threw several men who assaulted me against the wall. My size gave me an advantage most women don’t have. Books were an escape hatch for me too. I read constantly, walking to school, at night under the bed covers with a flashlight, after I finished my work in class. I went to the town library every couple of days and read all the books I could get my hands on including Wuthering Heights and Lolita, which came to our home because my mother was a member of the Book of the Month Club so popular in the late 1950s. My mother hid the then shocking novel Peyton Place by Grace Metalious under the cotton batten in her jewelry drawer, but I found it anyway and read it too. I also fantasized about riding horses, and as a kid, I did ride a few but they secretly scared the daylights out of me. I found the courage to be different later than you.

JS: What was going on with you as a young woman? You started out as a journalist with ambitions to write fiction in the 1960’s; became a performance artist and single mother in the 1970’s and then a novelist and professor who moved to New York City for a while to further your literary career.

SS: My memoir is like a quest novel because I was searching for a place where I fit, and each new environment gave me something I needed to complete my quest. Margaret Atwood’s suggestion made me realize my life had followed the pattern set by Anna Swan who spent most of her forty-four years searching for a home that would accommodate her size. She never found it, even when she and her giant husband gave up the circus and retired to Seville, Ohio. Sadly, her two babies died. At the end of my novel about her, I have her say: “I was born to be measured, and I do not fit in anywhere. Perhaps heaven will have more room.” Because I didn’t face the same debilitating obstacles as Anna, I learned to accept myself and my body in a way that was never possible for her. Don’t bother trying to fit the gender script I told myself—be your own norm. How did you handle not fitting the gender script?

JS: When I was in high school, I wasn’t drawn to any of the boys, and my mother didn’t give me any sort of sex-education info (I had to ask my roommate about that when I got to college, and she was very informative). Because of the ADHD, I didn’t pay attention to traditional expectations, and, in addition to that, my mother and her sisters had jobs, were athletic, and were very independent. I was allowed to do pretty much whatever I wanted to do, and my real pleasure was watching the other kids and eavesdropping.

However, once my roommate (who had a boyfriend) told me what she knew, I got more interested in finding a boyfriend, which wasn’t easy if you went to a woman’s college. I tried mixers and met a few guys, but that was when I realized that I wanted my boyfriend to be taller than I was. In December of ’69, Yale invited some Vassar girls to come to New Haven for a week and go to classes to experiment with coeducation. I enjoyed it, and then, in the Yale Daily News, I saw a picture of the center on the basketball team, on one knee, next to a ball, and smiling. He was so handsome that I couldn’t resist looking for him. Someone told me his college and room number, and I went and knocked on the door. When he opened it, I said, “Hi! I’m your new girlfriend!” and walked into the room. And it turned out that he hadn’t dated anyone, either, so it was the perfect way for both of us to come to understand relationships and love. We both loved travel, history classes, and making jokes, and I loved the way that he had accustomed himself to being 6’10”. But let’s go back to books for a minute? Is there a relationship between writing and fiction and unusual height?

Being unusually tall makes you feel set apart because mostly everybody else sees someone with the same weight, height and coloring every day.

SS: Why don’t you answer that question first? I’m curious to hear what you think.

JS: I think the relationship is between fiction writing and simply being unusual. Almost all of the writers I loved in high school and college—Dickens, George Eliot, Jane Austen, Agatha Christie—were outsiders in some way, and so they became observant, and then curious, and then eager to find some way to sort through what they were observing and turn it into something logical and understandable. One of the main things you learn when you start reading and then writing is that each writer is unique, and that gives you permission to investigate your own unique qualities. And then it all gets more interesting, and you can’t stop.

SS: I agree. A lot of writers I know, including myself, felt like outsiders growing up. Being unusually tall makes you feel set apart because mostly everybody else sees someone with the same weight, height and coloring every day. But I didn’t know any people who looked like me and the fact that I couldn’t see myself reflected back to me in the world was a strange, lonely feeling.

JS: How did your time living as a writer affect your quest?

SS: I lived in New York off and on through most of the 1990s when American male novelists like Norman Mailer, Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis achieved rock star status and my friend Kathy Acker was writing her performance art style of novels. I was in Aphrodite Mode. (No, it’s not a fashion account on Instagram.) It meant putting pleasure and fun on an equal footing with my work and I flitted from man to man without any intention of settling down. In those years, Gordon Lish was an important editor at Knopf encouraging his coterie of writers to place themselves in jeopardy in their stories. Many of my New York writer friends took his class. He would stop them reading their work out loud if they began to bore him and order them to go back to their last provocative sentence and start again.

The example of Lish and many of the literary people in New York encouraged me to drop a leftover notion from my Presbyterian childhood that making a show of yourself was somehow embarrassing and disgraceful. Why did it take you so long to understand, I wondered. Get out there and perform yourself. My size was a bonus not a drawback. That’s one of the big gifts that America has given to the world—celebrate who you are and what makes you unique. Unfortunately, that gift has been tarnished by the Trump administration’s narrow definition of who an American is.

JS: You also lived in Greece. How was that part of your search to find a home as a writer and a woman?

SS: I stumbled on Greece by accident when I was invited to teach a writing workshop on the island of Skyros and was struck by the way the Greeks accepted their bodies. They didn’t need to look like movie stars or online influencers to enjoy the physical pleasures of daily life in Greece. After the workshop, I met the late feminist theologian Carol Christ who was my height of six-two. I went on her tour of Minoan shrines and was impressed by the groundbreaking feminist scholarship of Christ and the late Marija Gimbutas, an archeologist who believed these ancient sites were places where Minoans worshipped a goddess deity. Christ’s books describe embodied spirituality which involves an understanding of the body as the portal to spiritual wisdom. I personally don’t believe in a male or female god, but it was liberating to discover another way of thinking about our bodies instead of the traditional Christian belief that the body, along with physical reality, is something we need to escape. Carol Christ’s philosophy encourages people to inhabit their bodies, and in her later books, she said that anyone, no matter who they are, can represent the divine.

JS: What did Greece teach you about living inside a big female body?

SS: Let me leave you with a story. I went with the late Carol Christ to a local hot spring on the island of Lesbos where naked Greek women of all sizes and shapes and ages were bathing together and having fun, and for a moment, I saw them without judging their bodies. It was as if I was looking at them in the same accepting way that I might look at a beautiful garden or a pleasing grove of olive trees. Now that’s progress, isn’t it?

JS: Amen to that.

*

Susan Swan is a novelist and non-fiction writer, a professor emerita, and a recipient of the Order of Canada. Her books include The Wives of Bath, The Biggest Modern Woman of the World, What Casanova Told Me, The Western Light and Stupid Boys Are Good to Relax With. She is also co-founder of the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction, the largest literary prize for women and non-binary writers in the English language publishing world.

Jane Smiley is the author of multiple works of fiction and nonfiction, including Perestroika in Paris, A Thousand Acres, Lucky, and Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel. She has won several awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for A Thousand Acres.

__________________________________

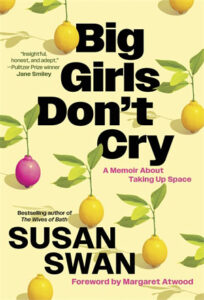

Big Girls Don’t Cry: A Memoir About Taking Up Space by Susan Swan is available from Beacon Press.

Jane Smiley

Jane Smiley is the author of numerous novels, including A Thousand Acres, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, and most recently, Some Luck, Early Warning, and Golden Age, which make up the of The Last Hundred Years trilogy. She is also the author of five works of nonfiction and a series of books for young adults. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, she has also received the PEN USA Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature.