Quintan Ana Wikswo’s new collection of short stories, The Hope of Floating Has Carried Us This Far, is available June 9th, from Coffee House Press.

Maxine Chernoff: I was delighted to discover the beautiful photographs throughout your short story collection. What is the relationship between the photographs and stories? I found myself agreeing with Alice in Wonderland: “What is the use of a book without pictures?” Illustrated literary fiction is quite rare. Your illustrations are even more unusual because they are abstract, and they don’t depict what’s happening in the story. I’d like to ask the opposite of Alice’s question: what do you think is the use of a book with pictures?

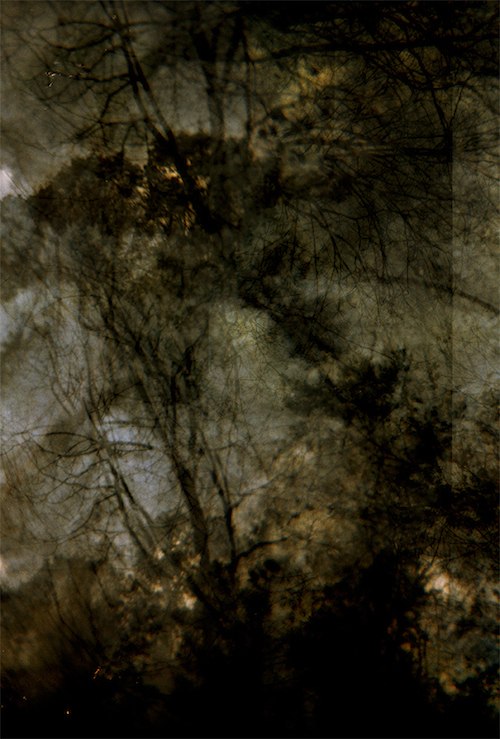

Quintan Ana Wikswo: In the book, the verbal and visual exist in a visceral pas de deux. When we are in love, when we are in trauma, when we are fighting for survival or captivated by a hypnotic sunrise, our brains create a visual dreamscape—surreal, shape-shifting, abstracted—that stays with us as long as we live. These images don’t exactly document the facts of what happened—they form an emotional landscape for the psyche.

I’m fascinated by the sensual cognitive rhythm of this process, especially the pauses that give us respite between thinking and feeling. We listen, then look around, our eyes lingering here or there. Our brain whirs and hesitates as it untangles new language and sights. We navigate our lives with our senses, and glean and process life visually through our eyes, and verbally through our mouths and ears. The book’s juxtaposition of photographs and text is a tribute to this dance of the brain.

I make my photographs using salvaged military and government cameras from fascist dictatorships—they were designed to document warfare, yet survived long enough to create fine art. Theirs are the true eyes of this book.

I adore illustrated books whose images amplify a sense of wonderment—images that become open windows to an unfamiliar world. The notebooks of Frida Kahlo and Egon Schiele are marvelous lightning bolts from the sublime. Love letters between the verbal and nonverbal psyche. Not all illustrated books are alike—some confine the imagination, and reduce the cosmos to predictable human conventions—a good example is children’s books in which all the characters are blond and white.

I have synesthesia, and Temporal Lobe Epilepsy in both hemispheres of my brain. The two hemispheres of the brain are intimately linked, and I like to imagine the intricate fireworks in the cerebral cortex as the visual center communes and crosses swords with the language center. A few years ago, a seizure took away my language processing for several months. But within hours, my visual cortex had become tremendously amplified and colors, shapes, and patterns came alive with a ferocious intensity. That’s when I started taking photographs. During the creation of the book, I wrote stories when my visual processing was impaired, and made photographs when I lost the capacity for language.

While I was making this collection, I scrawled a passage from Virginia Woolf’s The Waves in my sketchbook—I find it gets to the viscera of the language and image question:

How tired I am of stories, how tired I am of phrases that come down beautifully with all their feet on the ground… I begin to long for some little language such as lovers use, broken words, inarticulate words, like the shuffling of feet on pavement… Lying in a ditch on a stormy day, when it has been raining, then enormous clouds come marching over the sky, tattered clouds, wisps of cloud. What delights me then is the confusion, the height, the indifference and the fury. Great clouds always changing, and movement; something sulphurous and sinister, bowled up, helter-skelter, towering, trailing, broken off, lost, and I forgotten, minute, in a ditch. Of story, of design, I do not see a trace then.

MC: In these stories, disasters in war and love trigger peculiar unexpected metamorphoses—is this process perversely hopeful, as the title hints? Cataclysmic apocalypses such as hurricanes, political coups, and military invasions find equal footing with lovers’ quarrels, broken romances, and erotic negotiations. Instead of cause for destruction, these catastrophes become opportunities for transformation—especially from human to non-human.

QAW: I’m mesmerized by our rare opportunities to go off the map of the known world, and into uncharted existential territories. Often our true selves are revealed at moments of great personal peril—like love and war—when everything superficial has to be jettisoned. Those moments force us to radically redefine ourselves in ways we never imagined. We are forced to become more or less than human. In that moment of transformation, I’d like to think we can become anything: an eel, a crow, a coward, a ghost, a particle collider, a murderer, a heroic lover, or simply a lichen.

I wrote this book while I was living in Germany and Eastern Europe, working on a project about post-genocidal communities. Every day, I thought about how we handle the aftermath of great disasters from which we cannot possibly survive intact. What happens after the comprehensive existential destruction of our bodies, minds, and psyches? In what new form do we emerge from the destruction of an established self?

I started wondering about how transformation can become a liberation strategy more powerful than simply hoping to heal or survive. As humans we are weighed down by the idea that trauma breaks us, and we worry that we cannot be repaired. Perhaps repair is not the best and highest goal. Every inhabitant of the cosmos—animal, vegetable, and mineral—thrives through metamorphosis. Creation itself cannot occur without radical transformation, even destruction.

I’m interested in war and romantic love because they are two profoundly unstable states in which normalcy vanishes, familiar boundaries dissolve, and we face the ultimate intimate encounter with dreams and nightmares, fantasy and horror, the unreal and the sublime. Our lives, our sanity, our autonomy are all part of a volatile chemistry experiment. Perfect conditions for radical change.

The title is drawn from the Water Tests of the medieval witch trials, in which misfits and outcasts were thrown in the water—if they floated, they were burned as witches. And if they sank, they drowned. Either way, the accused was going to be murdered. Sometimes events force us to stand outside conventional existence and inhabit ourselves more honestly, earnestly, and sincerely. When a witch hopes to float, she or he lives—even if briefly—as a true self, an honest self, a no-longer-everyday self, no matter how transgressive, and no matter what the consequences.

MC: There’s a mad scientist aspect to your work—how do physics and dark matter and the like find their way into a work of fiction? You have misfit geologists and mathematicians searching the tunnels of the Large Hadron Particle Collider for mythical sea creatures, Oxford ornithologists find themselves trapped in prison ships, and spiral-obsessed physicists get far too close to the black hole eye of a hurricane.

QAW: I grew up as the homeschooled child of a devout preacher and a physicist, who raised me on contradictory creation stories in an attempt to justify the world they’d plunged me into. Their stories were all I had to work with, and were perplexingly fantastic and surreal—atoms versus Adam, miracles and states of matter, heaven and hell, charged particles, good and evil. God flies to earth in a pillar of semen and fire and makes a baby with a mortal woman. All matter in our bodies is comprised from stardust. The earth is flat, until it becomes a sphere. We rest comfortably at the center of the universe, until we are banished to orbit a massive fireball called the Sun and eventually explode. Rods become snakes. Food falls from the sky. Moving hands write in fire on the walls. I came to realize that our experience of passing in and out of existence is an ignorant and uneasy one, filled with mad passions but no answers, only theories. We sing comforting songs to ourselves. We hope for things we cannot see or name.

I was born in a hospital located right on top of the Stanford Linear Particle Collider, and was surrounded by brilliant people in search of preposterous, invisible things. My first babysitter led the team that detected quarks. Several decades later, I found myself in a love affair with a dark matter physicist working on the construction of the Large Hadron Particle Collider at CERN, in Switzerland. As the relationship disintegrated and his team lost confidence in their experiments, I thought about the arrogance of love and science, our illusions of control, and the beautifully absurd pursuit of union with the cosmos or the other. I spent days below the Alps exploring the unfinished tunnels, and marveling at the energy we willingly expend attempting to address our abject ignorance of who we are and why we are here. “The Double Nautilus” was my reaction to that experience, and how—deep underground and profoundly disillusioned—I created my own fantastical concept of the ideal future partner. My quest seemed no more or less quixotic than the physicists’ dreamy search for the God particle (which, of course, seems to have now been found).

Science says a lot about agency—we start out with questions about the nature of gravity, and we end up evaporating the inhabitants of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. My father’s family worked on the Manhattan Project as chemists, mathematicians, and geologists. After the war, they moved to isolated rural areas and took up peacetime activities like astronomy, ornithology, and clock making. Perhaps in an attempt to transform their talents into something less lethal, perhaps to vanish into a natural world where they stood as observers instead of agents of inadvertent destruction.

Like science and religion, storytelling is just one more method for questioning and considering how things are, and imagining how things might be. Techniques for challenging—as well as enforcing—the limitations of our own theories and beliefs. And both offer seductive charms that allow a human—or a group of humans—to radically refashion collective and individual realities. Alchemy.

MC: Between the stories and their companion photographs, you seem to have a knack for seeking out unusual sites and places with complicated histories and spending a lot of time learning their secrets. How do you find these locations? How does working at those sites influence your writing? There’s a mesmerizing sense of timespace travel in these stories, which seem to simultaneously inhabit ancient mythological eras and the present day.

QAW: I tend to plant my existential questions in painful and poetic soil that lends itself to quantum superpositions… places that exist across multiple states and multiple realities simultaneously. For example, the forest in “The Cartographer’s Khorovod,” looks much like any other, except for the Hessian mercenary who stands there in 1777 and quits the British and joins the Revolutionaries. At the same tree, suburban real estate developers fantasize about six-lane highways, intermingling with Algonquin warriors who are sharpening their weapons for all eternity. A few steps away, the trucker who idles a big rig on the freeway thinks the big tree would be a good place to urinate.

Places contain narratives, and are themselves a kind of Schrodinger’s Cat—the mercenary is simultaneously a daytripping opportunist, a disloyal traitor, and a bravely conscientious hero. Incompatible states that somehow coexist. Invisible to hikers and suburban real estate developers, yet visible to historians and similar timetravelers. I typically go to a particular site and work there for long periods of time, considering the entire known history of everything that has happened at that place. I sit with a typewriter and my cameras, and drift through its layers, harvesting out the stories that I see and hear.

I started creating this book in the Baltic—Estonia, Finland, Latvia, eastern Russia, and Lithuania. I tracked down various sites where Vikings, Christian Crusaders, Germans, Nazis, Russians, Soviets, NATO allies, and insurrectionists of various stripes had erected military installations and shrines. It became impossible to tell the difference between the two—a tangible collision and superimposition between pantheons. Pits in the earth that had once hidden Nazi tanks. Roadside totems to the eel goddess. Old plywood factories used to make walls for slave labor camps. Ravens gathering over a mass grave. Clandestine Russian military centers with ambiguous contemporary intent.

These sites—like the characters in the stories—have experienced the absence of ultimate control. Like the characters, they have been subjected to a moment in time that robs them of their own autonomy. The earth can do nothing while it’s clawed apart by tanks and bombs, bulldozers and gas stations. The landscape itself, the earth, is forced to evolve, to become something else, for better or worse.

More than ever, we are a migratory species, and I wonder why we walk the earth without exactly inhabiting it—the way we sometimes look at each other, but don’t see. We can’t really touch or feel time. It evades our five senses. But looking at place, it’s possible to perceive time, and to move through it. Place is timebending.

We have a tendency to exoticise distant places, but there is no mundane spot on this earth. My corner bodega was likely once upon a time a nursery for pterodactyls. One of the beaches in “The Anguilladae Eaters” is Point Dume, in Malibu—a notoriously brutal site of whale slaughter and rendering. It co-exists extrasensorily, semi-silently, within the Southern California seashore superficiality factory, as does the Spanish genocide against the Chumash and other indigenous peoples. These events are invisible motes in the sky-blue eyes of Pamela Anderson. These are almost wormholes of meaning. One human’s Saturday afternoon surf spot is another human’s cemetery. I tracked down four animal-slaughter beaches in the world, and each contained these nested stories—one beach was also the runway for the first airplane flight over the North Pole. I went in search of something small, and let the quantum superimposition search for me.