Sophia Chang on Entering the Wu-Tang Clan's Inner Circle

"She’s down with Wu-Tang! And that’s all you need to know!"

In early 1993, I received a demo tape that didn’t get thrown into the boxes under my desk because there was already a buzz building around it. The slightly worn black Maxell 60-minute cassette had three titles scrawled on the narrowly lined cardboard insert: “Protect Ya Neck,” “Method Man,” and “Tearz.” At the bottom was the contact information for a Prince Rakeem, the producer and the founder of the collective, as I would later learn. I inserted the tape into my cassette player as I had done hundreds of times before, but the result was like nothing I’d ever experienced.

First, there were nine guys. Nine. And each killed his verses with unique vocal, lyrical, and delivery styles. Then there were the beats, which were like the underbelly of the city itself. Not the beautiful, romantic skylines that I’d seen in movies, but sidewalks piled high with trash bags, subway tracks filled with rats, and the massive crime-ridden projects of the 1980s and ’90s at the height of the crack era. There are countless songs that marry the powers of incredible beats and killer rhymes, but there was an element here that went beyond technical mastery: a combustible energy. Prince Rakeem—now known as RZA—somehow harnessed this tsunami and mixed it in a forty-ounce bottle for our consumption.

It takes a master alchemist to flawlessly highlight and integrate so many disparate skills and personalities on what we called a “posse track” back in the day. Even the intro to “Protect Ya Neck” was ominous and compelling: the song opens with kung fu flick samples and launches right into “Wu-Tang Clan comin’ at ya! Watch your step, kid, watch your step, kid . . .” ODB started his verse by singing his “come on, baby baby, come on baby baby, come on, baby baby, come ooooonnn,” which could be the lyrics to an R&B love song, but then goes straight into “first things first, man, you’re fucking with the fucking worst / I’ll be sticking pins in your head like a fucking nurse.” The song was an embarrassment of riches and I wanted more.

I played that demo for anybody who would listen. I was a true Wu-vangelist. I couldn’t sign the Clan because RZA famously asked for a nonexclusive deal—meaning each of the members of the group could pursue solo deals at other labels—but I was determined to meet the man regardless, because he was clearly a singular talent who would have an exceptional future, and I was intrigued by the mind behind the music. The opportunity came a few months later when I received a demo for the Gravediggaz, the group that RZA had founded with producer Prince Paul, the creative impetus behind De La Soul. I set up a meeting with him immediately.

It was a hot summer day. I wore a Club Monaco sleeveless long dress in a small navy gingham print. RZA was late, which was to be expected, because few rappers are punctual. An artist’s tardiness was inconvenient, but today it was unnerving because I was so excited to meet him. I kept looking at the clock, worried that enough time would pass to signal that he wasn’t coming. Finally, the receptionist called to tell me he’d arrived. I ran to the lobby to meet him. He was gangly and taller than I’d expected, as I would learn almost all of the Clan were. He greeted me with “Peace, Soph” and shook my hand warmly.

“She’s down with Wu-Tang! And that’s all you need to know! Who the fuck is you to ask her where she’s from?! Don’t you ever disrespect her again!”

We went down the street from Jive to Lox Around the Clock for lunch. We talked about the Gravediggaz, their horror movie aesthetic, how he had come to collaborate with Prince Paul, and what they were looking for in a label deal. I then grilled him with questions about the Clan. He told me that most of them had met in Staten Island, which they called Shaolin. Some of them grew up in the Stapleton Projects, others in Park Hill, aka Killer Hill. Most of them had run in the streets, and they bonded around music and kung fu flicks. When it came time to record the demo, RZA said each member had to show up with fifty dollars cash to pay for studio time. RZA had a unique worldview and clear vision for the group. When we parted, I thought, That’s one of the smartest motherfuckers I’ve ever met. As I walked north on Sixth Avenue, wondering when we’d next meet, he called out, “Soph!”

I turned quickly.

“Next time lunch is on me!” He hasn’t let me pay for a meal since.

Talking to RZA was like entering a house that has endless rooms, each more fascinating and complex than the last. He spoke with such intelligence, insight, and energy about everything. Beyond his business acumen and musical genius, I felt a strong spiritual connection to him. Though he had dropped out of high school and I had graduated from university, it was manifestly clear that he was far more erudite than I was, the ultimate autodidact. Guys like RZA and Chris Lighty helped me see that formal education is not necessarily the key to success in business, which is partly why I paid no mind to my mother’s entreaty that I go back to Vancouver to earn an MBA. I hoped to learn from RZA via his words and actions. I made sure to stay in touch. To this day, I remember his home phone number and address on Staten Island, down to the zip.

Soon thereafter, RZA invited me to the studio, where I met the other Clan members. It’s always a privilege to be in the room when people are creating, but this meeting was particularly fascinating because there were so many of them, and I was curious to see what the seemingly unwieldy process would be like. GZA, the Clan elder and the head of Voltron, was laid-back and almost a little shy; Inspectah Deck was low-key with kind eyes that took everything in; U-God was full of energy and verve and immediately started calling me Miss Chang, as he does to this day; Masta Killa clasped my extended right hand in both of his while looking me dead in the eye as he said “peace” with a quiet intensity; Raekwon the Chef had an easy smile and cocked his head when he listened to me talk, as if he was hearing something others weren’t; Ghostface Killah leaned in to greet me because he’s six feet three inches and looked at me with warmth and curiosity; then there was Method Man, who hugged me and enveloped me completely in his tall frame in a way that said, “I got you, Soph,” from the gate. He not only said it, he walked it.

One Saturday afternoon I went to see the guys in the studio. I jumped down the stairs of my second-story walk-up, two at a time, in a white T-shirt and gray terry shorts that I’d nabbed at a DKNY sample sale. I raced up Seventh Avenue to Battery Studios, which was located in the same building as Jive. There was a heat wave throttling New York City, already choking with tension and humidity. When I got to the studio, I was sweaty and relieved to feel the blast of air conditioning. As I entered the control room, Method Man jumped up and dragged me by the hand into the back lounge, barely letting me greet the rest of the guys.

“Sophie! I just got my video and you’ve gotta see it!”

At this point, the world had seen only one music video from Wu-Tang for “Protect Ya Neck.” That song had catapulted the Staten Island collective into the hearts and minds of the hip-hop cognoscenti, and everyone knew their rise would be meteoric. Everyone also knew, after hearing just fourteen bars, that Method Man would be the group’s biggest star. I was about to get a personal sneak preview of the video for his solo song, one of only two on the album, “Method Man.”

He led me to a black leather love seat and gently patted the worn cushion with his big strong hand. The scars on his knuckles marked the countless times he must have used his fists to defend himself, his turf, his loved ones. I sat back as he slid the VHS tape into the machine and waited for it to click into the spools before pushing play. I slid over, expecting him to sit next to me, but he shook his head. “Nah, Sophie, you sit. I’m good.” He receded into the wall like a long, lean phantom at an angle that allowed him to study my reaction. Sitting directly across from me, next to the TV, was Jamal, one of the Clan’s crew, also intent on watching me. Chilled by his cold energy, I saw clearly that he was trying to figure out how this little Asian woman, clearly not a groupie, had made her way into the inner sanctum. But I was there for Meth and ignored Jamal’s glare.

As the video played, my face broke into a huge smile, hands clasped in sheer elation. Like its predecessor, it was low-budget, grainy, and poorly edited, but the intensity and personality of the Clan were undeniable—in the video they brandished hoodies, Timbs, kung fu swords, and, of course, weed. And the song’s star shone like Sirius A: Meth’s raging charisma, spring-loaded agility, and scruffy good looks surged through the screen.

As the video finished, I started to gush but then Jamal interrupted me.

“Where are you from?” he asked, with thinly veiled hostility.

“Excuse me?”

“Where are you from?”

“I don’t understand what you’re asking me.”

That was a lie. I had been asked this countless times before. I chose to play naive because I was caught off guard and didn’t want to be adversarial in someone else’s house. Where are you from? is a loaded question for people of color. Like its evil stepsister Who are you?, it’s a question that’s not asking, but saying something like, “Who do you think you are to be in my world, because you clearly don’t belong.”

“Where-are-you-from?” This time emphasizing each syllable to drive his point home.

“Well, if you’re asking my heritage, I’m Korean Canadian. If you’re asking where I live, I live in Manhattan. If you want to know where I work . . .”

Before I could finish, Meth flew between us, yelling at the top of his lungs, “That’s Sophie Chang and she’s from Shaolin! She’s down with Wu-Tang! And that’s all you need to know! Who the fuck is you to ask her where she’s from?! Don’t you ever disrespect her again!”

Without a single raised voice or sudden gesture, it was clear that these boys had walked many times on the razor’s edge of danger and would throw the fuck down in a New York heartbeat.

I sat bolt upright, eyes wide, mouth agape. This total sweetheart, who had a kind word for everyone, transformed before my eyes into a fury-breathing dragon. As his words shot through the air like poison darts, I saw he was rocking a cape emblazoned with a giant M, rippling in the wind of his fury. He sucked all the oxygen out of the room and took up every cubic inch of space. In that moment, I swore my undying allegiance to Method Man. Not only did he defend me, an Asian woman whom he barely knew, against one of his own, but he also instantly understood the racial subtext of the query. His defense of me was at once potent and poetic. From that day on, each time I saw Meth, I knew he was watching over me. This was the first time, but far from the last, he would bring da ruckus on my behalf.

Despite their distinct and varying personalities, there were common elements among the members of the Clan: First, a sense that the Wu-Tang truly could be dangerous. Without a single raised voice or sudden gesture, it was clear that these boys had walked many times on the razor’s edge of danger and would throw the fuck down in a New York heartbeat. Second, that they loved each other unconditionally. Third, that they were going to be huge. “Protect Ya Neck” was already getting a lot of attention, but being there while they were working convinced me that the dam was about to break, and we would all soon be engulfed by their music. Victor Hugo said, “On résiste à l’invasion des armées; on ne résiste pas à l’invasion des idées,” which has been loosely translated to “there is nothing as powerful as an idea whose time has come.” Wu-Tang were, in fact, an invasion of both armies and ideas.

__________________________________

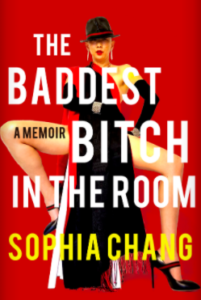

Excerpted from The Baddest Bitch in the Room, copyright © 2020 by Sophia Chang. Reprinted by permission of Catapult.

Sophia Chang

Sophia Chang is a Korean-Canadian music business matriarchitect who was the first Asian woman in hip-hop. She worked with Paul Simon and managed Ol’ Dirty Bastard, RZA, GZA, Q Tip, A Tribe Called Quest, Raphael Saadiq, and D'Angelo. In 1995, Chang left music to train kung fu and manage a Shaolin Monk who became her partner and father of two children. She also produced runway shows, worked at a digital agency, and is developing TV and film properties. Find Chang on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and at www.sophchang.com