Let’s start at the urinal.

Two men are standing unnaturally close to one another, which would ordinarily be a significant breach of urinary etiquette, especially when the dividers are as ineffective as they are here. But in this instance, the breach is entirely pardonable, because these two men, Jun and Arthur, have just gotten married. Also, they are wearing a gigantic tuxedo that’s been tailored for two people to share. The white shirts underneath are sewn together with a big bowtie on the top. The pants are appropriate for both a formal occasion and a three-legged race. The fly has been inconveniently placed.

Behind them, the wedding singer waits his turn.

In all the time Jun and Arthur spent planning for this big day, it hadn’t occurred to either of them to think about peeing. In order to approach the fly at the proper angle, Arthur has found it necessary to fold himself into Jun, one arm bracing for stability, the other trying to guide the trajectory. The endeavor plays out the way most weddings do, as a messy process with unexpected challenges that test the bounds of teamwork. But in the end, there’s a certain sense of relief.

Jun and Arthur are both in their early forties, and as with most gay men of their generation, their gay identities formed first as a matter of revelation and survival, next as a matter of pleasure and defiance, and finally as a matter of community and pride. When they were sixteen years old, ten years away from meeting each other, getting legally married wasn’t something they could imagine. And if they had, it would have felt like a Technicolor dream sequence. Their love formed when marriage was still out of bounds, and when the bounds changed with astonishing speed, it took them a while to decide the step finally being offered was a step worth taking.

The only way they could do it was in their own fashion. Some couples have a favorite song. Jun and Arthur have a favorite state of being, and that is song. Neither of them sings particularly well or plays an instrument with any proficiency. Instead they believe in the ever-present soundtrack, the perpetual playlist. Sometimes they control the dials, manipulating their sonic surroundings to enhance or alter their moods. Other times, they leave it to chance—not just by shuffling toward randomness, but often by wandering around Gothenburg and waiting for a song to come to them, lilting from an open window or roaring out of a bar. The life they share and the songs they share are inseparable. So when they planned their wedding they knew they wanted:

1) A theme-songed wedding

2) A song-themed wedding

The second of these desires leads to the first explanation of their costume. Just as each of their guests has come dressed as a favorite song, Jun and Arthur are dressed as a tune that fits the occasion far better than a large tuxedo fits two men of different heights: the Spice Girls’ mathematically simplistic yet philosophically rich ballad “2 Become 1.”

As for the desire to have a theme-songed wedding . . . well, that is where J, the man waiting patiently behind them, comes in.

J is a somewhat successful Swedish singer-songwriter. If you live outside of Sweden, it’s unlikely you’ve heard any of his songs on the radio . . . unless you are one of the bookish, folkish sort who listen to bookish, folkish stations that play bookish, folkish ditties. Then you might know exactly who J is.

The reason he’s here tonight is not a longstanding friendship with Jun and Arthur. Until they emailed him out of the blue, J had never met them. This may seem like a strange thing to do, but for J, it is not that strange, because on his debut album there is a song called “If You Ever Need a Stranger (to Sing at Your Wedding).” It goes like this:

If you ever need a stranger

To sing at your wedding

A last-minute choice, then I am your man

I know every song, you name it

By Bacharach or David

Every stupid love song that’s ever touched your heart Every power ballad that’s ever climbed the charts

You think it’s funny

My obsession with the holy matrimony

But I’m just so amazed to witness true love

And true love can be measured

Through these simple pleasures

They are waiting there for you to be discovered

I would cut off my right arm to be someone’s lover

Maybe I’ll meet her there tonight at the wedding buffet

I walk up to her when she’s caught the bouquet

Songs are not, by nature, self-fulfilling prophecies. It’s safe to say that Bing Crosby experienced many snowless Christmases, Michael Jackson notably did not heal the world, and Florence Welch had no idea what 2020 was going to be like when she proclaimed the dog days to be over in 2010.

Over the years, many devotees of J’s music have gotten in touch with him when their weddings are in the larval stage, asking if he’s available to put some musical colors onto the ceremony’s wings. Wedding singer gigs are usually more lucrative than busking, but J does not charge much for these efforts if (like Jun and Arthur) the couples are of modest means. Undoubtedly if you asked J as he waits for the urinal why he is here, he would answer, “Because of my song ‘If You Ever Need a Stranger (to Sing at Your Wedding).’ They were strangers. I am singing at their wedding.”

Still, there’s more to it than that. J just doesn’t see it yet.

Instead he sees Arthur adjusting himself back into his underwear and Jun angling to take his own turn at the urinal.

“J!” Arthur calls out. “We’re so glad you’re here! We’d shake your hand, but I think it would be best if we washed off first. It’s really hard to piss in this tuxedo!”

“It’s wonderful to be here,” J says, maneuvering around the pair to get to a stall that has freed up. “It’s quite a crowd.”

Jun and Arthur finish their effluent business by the time J finishes his own. They wait as he washes his hands, then wrap him in a two-armed, three-legged hug. When they step back, they take a look at what J’s wearing: a deep-red beret and a wine-dark shirt covered in balloons, a number of which have already been popped.

“Oh, dear,” Jun murmurs sympathetically.

In keeping with the wedding’s theme, J had planned to be dressed as Nena’s eighties classic “99 Luftballons,” even though (a) only about sixteen luftballons fit on his shirt and (b) the song in its original German is about a group of fighter jets that open fire on balloons they’ve mistaken for UFOs, starting a ruinous military spiral that leads to a world where “99 Jahre Krieg lieBen keinen Platz für Sieger”—“99 years of wars have left no place for winners.”

“What happened?” Arthur asks, assessing the red rubber carnage.

“Your nephews,” J answers. (The nephews are aged ten, six, and five, and collectively dressed as Kung Fu Fighting; the balloons didn’t stand a chance.)

Worried that his truthfulness has brought down the mood as only, say, the last lines of “99 Luftballons” can, J adds, “But it’s okay! I can be ‘Raspberry Beret’ instead.” (“Raspberry Beret” ends in a world where “I think I love her.” Better.)

“A Prince and two queens!” Jun exclaims.

Arthur groans, but there is affection in his protest.

J smiles at the sight of them in their absurd tuxedo. It is not the kind of smile that needs any thought behind it. His heart has grown so full that his mouth must lift.

The word for what he feels is tenderness.

That is the true reason he’s here.

There are a few standard questions J asks couples when trying to write their wedding song. But mostly, he improvises. He can measure immediately whether both people in the couple want him to be there, or whether only one of them is a fan and the other is merely humoring. If both are into it, the process begins.

J always starts with a simple question: “How did you meet?” (For Jun and Arthur, at a museum installation; Jun was the artist, and Arthur was doing the installing.) Then he might progress to “What did your friends first think of the two of you together?” or “What was your favorite date, from early on?” After that: free swim. “What’s the stupidest fight you’ve ever had?” or “What’s your favorite piece of his clothing?” or “What habit of hers went away after she met you?” Jun and Arthur talked a lot about the challenges of queer romance, how in their youth it felt antisocial to not be hedonistic, and how settling down now feels like a betrayal of youth, to some degree.

“So what does this wedding mean to you?” J asked.

“Well, it all comes down to Plato’s Symposium,” Arthur replied.

“Not to be confused with Plato’s Retreat,” Jun added, snickering.

Arthur pressed on. “Correct. Symposium. I’m sure you heard about it in school and thought it was boring beyond words, but it’s actually amazing, in a funny and touching way. It’s a bunch of Greek guys who come together, get absolutely wasted, and talk about love.”

Jun picked up the thread. “Aristophanes, a comedy writer who’s probably the drunkest of them all, recovers from his hiccups long enough to tell this story of how humans used to have doubled bodies. There were three different kinds: the double males who were from the Sun, the double females who were from Earth, and the androgynous who were half man and half woman and lived on the Moon.”

“The double humans started to mess with the gods, and Zeus got angry and decided to split them all in half—”

“—You probably know this part from Hedwig—”

“Can I finish? So, yes, Zeus split them up. But he did nothing to erase their memories. Our memories. So each of us walks around the earth looking for our other half.”

“And now I’ve found mine.”

“And I, mine.”

“So the wedding is when we’re scheduled to have the surgery to be connected again.”

They then explained to J their idea for the double suit.

2 Become 1.

J plays two sets at each wedding. The first is usually made of a dozen songs the couple has chosen, often a musical biography of their relationship. This set often includes “If You Ever Need a Stranger (to Sing at Your Wedding).”

The second set is exactly one song long, and it comes after the wedding toasts.

This is the song J has composed for the couple.

As J, Jun, and Arthur exit the restroom together, it is time for the first set.

It is a universally accepted fact that if asked to choose a song to kick off their wedding, 91% of all gay men will choose a song popularized by a female singer, and 78% of the time, that female singer will have died in tragic circumstances.

This is why J begins the night by playing a version of Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance with Somebody.”

For the wedding-goer, this song is akin to a call to arms. If you happen to have come to the wedding with somebody who loves you, it behooves you to step out with them onto the dance floor. If you did not come with a plus-one of that status, or with a plus-one at all, you must either discover something fascinating about the water glass in front of you or you must scan the crowd to see what your possibilities are. It is as if the wedded couple is daring you to be resentful, and some wedding-goers rise to the challenge. (Others check their phones.)

As if to democratize the dance floor, Jun and Arthur are not dancing with one another as much as they are dancing with the entire crowd. To J, this makes sense. If Jun and Arthur are going to dance with somebody who loves them at their wedding, and they are lucky enough to have so many loving friends and family members there, then they must spread their double-wide arms and dance with as many people as can fall into their open embrace.

For the next song, a jauntier than usual rendition of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” Jun and Arthur dance with their mothers—Jun’s is dressed as The Rainbow Connection, Arthur’s is a little more subdued Nights in White Satin. For the third song, they do not dance with their fathers—their families are supportive and progressive, but only to a point.

(In fairness, Jun’s father, a spirited Stayin’ Alive, would have been game. Arthur’s father, a more reticent Fly Me to the Moon, would rather not dance at all.)

Song by song, the revelry amplifies. As Jun and Arthur spin and swirl with an impressive level of coordination at the center, intrigues occur along the edges. Careless Whisper decides he can’t stand dancing with Father Figure anymore. Smalltown Boy works up the courage to ask Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) to dance, and now their hands are all over each other, much to the chagrin of Smalltown Boy’s ex, Personal Jesus, who is going through the motions of dancing with Caribbean Queen but keeps looking over his shoulder. A few drinks in, A Little Respect is singing along, not untunefully, as they and Friday I’m in Love sandwich Dancing on My Own. (She’s thrilled.) Meanwhile, Jun’s aunt and uncle, Eleanor Rigby and Hey Jude, are sweetly careening through their own soundtrack, in their own dance-time, her cheek resting on his chest, his cheek resting atop her head. Both their eyes are closed.

There are some artists who are compelled by the challenge of technical brilliance, striving solely to be recognized as a virtuoso of their craft. Others are drawn to create because creation is the only way they will ever know themselves. And still others are drawn to a life of artistry in the belief that it will connect them to other people. Sometimes this connection is conceptual, as if the artist desires to plug in to humanity itself. Sometimes it narrows into a generally perceived audience, a sea of nameless faces. And every now and then, the desire for connection narrows even further, and the art is created to draw a line to one specific person. The name and the body of this person may be intimately familiar to the artist. Or sometimes the artist creates the art to conjure this person into their life.

Who is J singing for?

Of course, he is singing for Jun and Arthur and their guests.

But also:

Whenever he sings the line “Maybe I’ll meet her there tonight at the wedding buffet,” he always looks to the crowd.

If there’s a buffet, he looks there first.

This time, he spots her immediately. She is looking at the food through heart-shaped sunglasses. But she isn’t reaching for a thing . . . because she’s in a straitjacket.

J smiles at this get-up.

She looks over to him on the stage.

He looks down at his guitar.

__________________________________

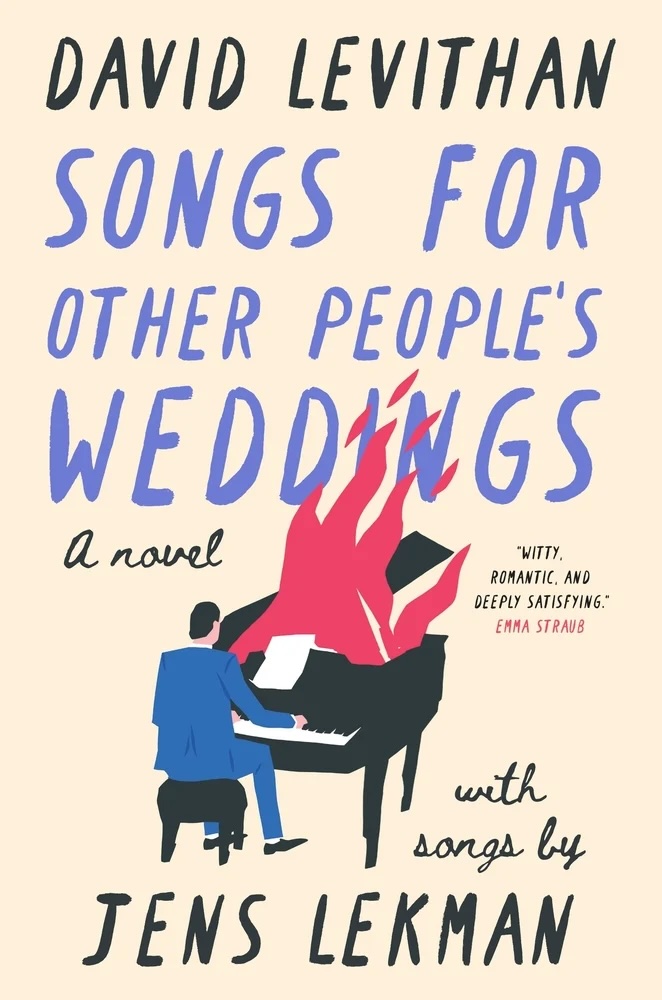

From Songs for Other People’s Weddings by David Levithan and Jens Lekman. Used with permission of the publisher, Abrams Press. Copyright © 2025 by David Levithan and Jens Lekman.