SATIN

Once my mother had an accident (moonlight, secateurs) when I was a toddler and there’s not much to say about it except some of me remembers and some of me does not. There were striped curtains, floor-length with vertical panels of cream and chocolate satin. They were soft and silky, and I liked to press my cheek against the wide band. The curtains were hung above a radiator, so the lining was always warm, and it felt safe, until it wasn’t.

Now that I know planting by moonlight is a thing it makes more sense, and I’ve pieced it together in a bric-a-brac fashion. According to folklore, root vegetables will start singing in the moonlight, and this is the best time to tend to them. These are the things I’ve collected together over the years:

—An aborted scream

—A scared-looking bird on a mound of wet leaves

—A used, flipped-over mattress inside a garage

Though this might be part of another memory—I am not always sure.

YOLK

Rania was born with an innie; her belly button has steep sides and a deep crevice. Once she tried to fry an egg on the hottest sunshine day—she lay down on a patio table and seasoned her skin with olive oil, and someone carefully cracked the egg onto her stomach. The cold white dribbled along her waist but the yolk, perfectly balanced, sat glistening in the hollow of her navel. Someone took a photograph. My sister is a talker by the way. Not only that but she’s a natural blagger. She’s also what I would call a relatable human being.

I have an outie; mine has untidy sides and is shaped like a volcano and probably wouldn’t support an egg.

SPRING-BLOOMING BULBS

There’s a bit of film that exists of our family in a garden. I am wearing a royal-blue romper suit with white piping, my hair in lopsided bunches. I am trying to blow bubbles. A hand—my mother’s, I think—is in view, passing me the wand, which I initially try to put straight into my mouth. She helps me dip and blow, dip and blow. I am inept at this simple task and becoming increasingly frustrated, then Rania makes her perfect debut on a purple tricycle, playing for the camera as she smiles, dismounts and takes the wand and the bottle and blows out beautiful, voluptuous bubbles. I am watching her with baðed concentration. I’m jabbering away in this film, I am not making language with any precision but uttering sounds just fine, no hesitation, no hint of a stutter, my clever two-year-old self.

It was my sister’s words that used to come out so quickly, in a torrential rush, that it was difficult to understand her in the early days. I was the only one who could translate her jumbled speech. All of the words would collapse backwards on themselves or come out in one effervescent stream until she eventually slowed down.

Sometimes I could see my mother turning her gaze from one daughter to the other, and I could almost hear the voices competing in her head. Some nights my sister and I would work our way quietly to the landing radiator where we would absorb the last of its heat and gently eavesdrop. My father, who’s always seen the glass half full even when it’s down to its last miserable dregs, would say, “Things could be worse, Jaan.” (He always calls her this when they are absolutely alone.) “We need to have some perspective.” This is my father’s favorite word in the whole world. “See, it could be worse: they are both healthy, growing girls; look at Arun’s twins, born so early and all their problems, and Tina’s daughter born with that birthmark cursed over the entire side of her face so she can barely open that eye, all these operations…”

“Oh yes, yes, Dilip,” she interrupts (she doesn’t have a pet name for him). “We are very lucky, this country is very auspicious—I should count my blessings that we all have our fingers and toenails and noses on our faces.” Then she’ll poke her hands in her hair to retrieve her hairgrips and we hear them tinkle onto the little enamel tray on her bedside table, then she’ll laugh a little, then a bit too much and a bit too loudly, and Rania will begin to stroke my back, and my father will slink a little deeper into the bedclothes.

BEFORE

My parents met the neighbors. On the right, Eena and Alfred Parker; on the left, at Number 14, were the Indians, the Panesars. A Sikh family.

“They are from the Jat caste and not like us,” said my mother.

“You don’t think anyone is like us,” pointed out my father.

“And you think everyone is like us: the sweepers of the street, they are like us…the English even they are also like us, I suppose?”

After their initial shy introductions, Eena’s eyes rested on my mother’s bulging belly. The following week she delivered three packs of booties and speedily knitted a shawl in yellow wool.

The children came. My sister Rania was late, but my mother managed to push her out with surprisingly little effort in the maternity wing in Central Middlesex.

“She will be called Rania,” my mother said, decisively. Dilip opened his mouth and shut it again, slightly taken aback by how quickly my mother was losing her meek expression of acquiescence.

My mother’s pregnancy with me was not an easy one—the enervating heat of August, combined with a toddler who demanded her constantly, sapped all her precious energy. She presented breech, and so was subject to uncomfortable manipulations by the hands of a bossy midwife who attempted to turn the baby. But baby-me remained resolute and unmovable. The doctors began to talk of C-sections and forceps. Bossy Midwife Number Two was dispatched and asked to shave the mother’s private parts and my mother began to weep.

“Don’t worry! You know Julius Caesar was cut out from his mother’s belly,” said my father.

“No, he wasn’t!” my mother contradicted, as she had always been an attentive student, particularly in Mr Verma’s classical history lessons. “Julius Caesar was not cut out of his poor suffering mother, it’s a myth.”

The baby did come my mother’s way, but not only was I feet-first, I also had the cord wrapped around my neck, twice for luck. Also, I was a crier. All babies cry but I seemed to cry all the time. With my sister it had been an easy age-old pattern—Rania would cry, my mother would fasten her to the nipple, she would fall asleep and then would feed again a couple of hours later. At night she would fall asleep with her baby at her breast, and the baby would find and suck her nipple any time at her leisure. The two of them would perform this dance till presumably my mother’s milk changed flavor, or Rania became bored of the dance, and one day jumped off the bed and walked away from my mother’s breast towards the fridge. But nothing in the world would settle me.

My mother was attended by a health visitor who was suspicious about Indian mothers and their baby-mother-habits, and although my mother seemed compliant, Linda Norton suspected that she ignored her advice when her back was turned, resorting to herbs and powders to alleviate colic symptoms and teething. The health visitor wrote up in her report that she was of the opinion that my mother had applied unsterile chappati dough to her breasts in an attempt to cure severe bouts of mastitis. My father, who has always been the curious sort and could never resist an open book, peeped at the notes whilst her back was turned and she was weighing little me on her scales. He threw the appalling Mrs. Norton out of the house.

__________________________________

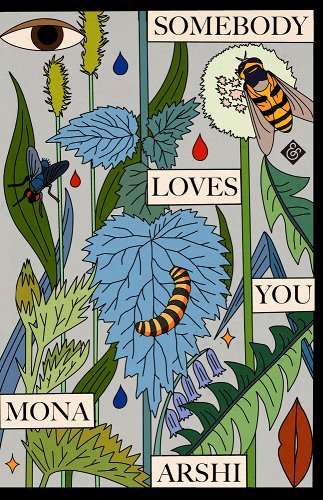

Excerpted from Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi. Copyright (c) 2021 by Mona Arshi. Used with permission of the publisher And Other Stories.