Some Writing Advice: Don't Take Others' Advice

Guy Gavriel Kay on Doing Whatever It Takes

I am, more or less, allergic to writing advice.

This is a problem these days, because writing advice is floating in the air like pollen in springtime, I await the Top Ten List of Top Ten Writing Tips. (I may have already missed it.) Writing advice is an industry on steroids. People everywhere tell you not to use italics.

One form the game takes is to tell people where and when they should be writing. I recall seeing last year someone advising all writers to take a run or a brisk birdwatching walk first thing, to get their creative juices flowing. But what if one can’t fit in that run or walk? What if it is January in Minneapolis? Or you have kids’ car pool? What if what gets your juices flowing is too much coffee, and Vivaldi or The Smashing Pumpkins played very loud? What if you are deeply averse to morning and your creative brain activates (on a good day) at 3 pm?

As to where to write, I always say: wherever you find that you do write. It is so intensely personal, the creative process. (It is also intensely personal what we want to write, what we aspire to do with our work, but that’s another essay.)

Some need that fabled room of their own, some have lives that don’t allow it to be more than a fable. Some work best in a cafe, with or without ear buds. Some co-opt the kitchen table as soon as the kids are at school, or napping. Some write on buses or subways, or at their office desk at lunchtime when they are supposed to be playing Fortnite like a decent person. (A few don’t wait till lunchtime.) Some write in bed, as Edith Wharton, Proust, and Truman Capote did (not same bed). Some in a tiny boathouse, like Dylan Thomas. “I’ve written on scraps of paper, in hotels on hotel stationery, in automobiles,” said Toni Morrison in an interview.

I still have a vivid memory of sitting next to Sir Terry Pratchett in front row seats at the closing ceremony of a long-ago conference where we were the guests of honor. We were being thanked by the Chair. Terry had his laptop open as the remarks unfurled. He was writing. New words in a novel. The chair named him, applause began. He put the laptop down, went onstage, spoke wittily and generously, came back and resumed writing. If he wasn’t such a splendid man I could have hated him for being able to do that.

There are no rules. That’s my main contribution to this discussion. Often people seizing on a writer’s advice have been shopping to find the established figure who tells them to do what they already like to do. “I write better after two beers! Just like Mercedes Rumbelow!” (I know of no Mercedes Rumbelow, I hasten to make clear, and refuse to google the name.)

When asked how I do things myself, or how I started, I always preface an answer by saying ‘This is anecdotal, not prescriptive.” Sometimes anecdotes are interesting (as often not!), but when they are used as how-to guides, I worry.

So, purely as an anecdote, I’ll say that I wrote my first two novels in a fishing village on the south coast of Crete, during two separate winter stays there. I paid $4 a night for my first room. It had a shower! If this appeals, and circumstances allow, you have my enthusiastic permission to try this sort of thing, this not at home.

I was young, had just finished law school, and had vowed (to the nine gods, like Lars Porsena of Clusium in the poem) to take a year before entering what I assumed would be a life practicing law: to see if I could begin—and finish—a novel.

Also: I had been in love with the myths and history of classical Greece since I was a kid. I bought a battered German typewriter in the flea market in Athens and lugged it on the overnight ferry to Crete. It had an umlaut key!

I picked the hotel in my village that was most remote from the seductions of the harbor. I was there to write. I was the first of the long stay travelers to leave the bar every night. It was called Zorba’s, of course. There is a law in Crete that says one bar in every town has to be. I kid. Probably.

And in that enforced distance from “life,” from daily or late night distractions, I deployed Lawrence Durrell’s lovely formulation (written in Greece!), that writing involves “art/Conspiring with introspection against loneliness” and I did produce a novel. And then I did it again, same village, three years later. That one was published.

This is a story. Offered in the hope it intrigues or amuses. It is not a template. I don’t think there are templates for the creative process, beyond the very basic, obvious one: if you don’t do it, it won’t get done. Putting in the hours. Trudging up the hill, metaphorically, when the cool people are still dancing.

Going away worked for me. It continued to for years afterwards, it became a pattern, maybe even a habit… I wrote novels in many countries, until our first child entered school and I learned that though we speak of disciplining our kids by grounding them, they actually ground us. You don’t go abroad with facility when the school years arrive.

I learned to write around drop off and pick up and homework helping. And to remain acutely aware I was lucky: that single parents, as an obvious example, are as constrained by these duties (adding love) as anyone working a full time job while trying to find focus and time to be creative.

So, upshot? If you don’t have that room that’s all yours; if your mornings don’t involve binoculars and cardinals, but making breakfasts, school lunches, then hurtling to get to work yourself; if what you have is a café on weekends where you write for a stolen hour, don’t let anyone tell you you have to take a brain-cleansing run at dawn, or do an hour of yoga before you can truly access the sacred waters in the deep well of art. On the other hand, if running or yoga (or running and yoga) work for you, do it, or them!

Get to those waters however you can. Accept that art happens in the midst of life and life changes on you and changes you, makes demands, imposes constraints. Do what you can through and around those, and if someone’s suggestions help, make you feel better—that’s all right, too! Just don’t let anyone’s words make you feel inadequate, not properly committed, unworthy.

Everyone has anecdotes, sometimes they are interesting, sometimes they can get in your way. Make your own call. Don’t assume that because someone has had a measure of success they can tell you how to do it.

Though I do advise, having read my Chekhov, that if you show an umlaut in act öne, you do have to use it in act three.

__________________________________

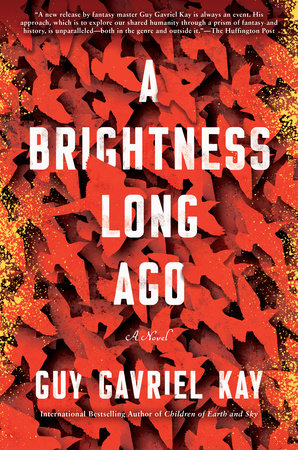

Guy Gavriel Kay’s A Brightness Long Ago is out May 14, 2019, on Berkley.

Guy Gavriel Kay

Guy Gavriel Kay is the international bestselling author of All the Seas of the World, out now from Berkley, and fourteen previous novels, including the Fionavar Tapestry series, Tigana, The Last Light of the Sun, Under Heaven, River of Stars, Children of Earth and Sky, and A Brightness Long Ago. He has been awarded the International Goliardos Prize for his work in the literature of the fantastic and won the World Fantasy Award for Ysabel in 2008. In 2014 he was named to the Order of Canada, the country’s highest civilian honor. His works have been translated into more than thirty languages.