Some Things You May Not Have Known About Edith Wharton's Dog Obsession

On the 155th anniversary of Wharton's birth, a tribute to her very favorite thing

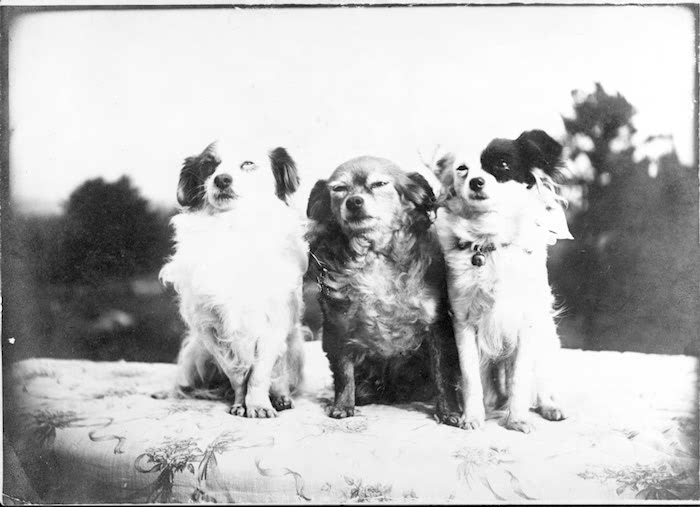

If you know anything about Edith Wharton—besides the fact that she was a brilliant writer and the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for literature, for The Age of Innocence, of course—it’s probably that she was an above-average dog-lover. And she was—to the point of near-obsession, and, I’d wager, some pretty clawed-up shoulders. Some say that Wharton, who had a troubled and childless marriage, substituted dogs for offspring, which may have some truth to it—but only some, since her love of canine companions started at the ripe old age of four, when her father gave her a Spitz called Foxy, a dog who, she said later, “made me into a conscious sentient person.” Today, on the 155th anniversary of her birth, it seems only fair to honor Wharton’s memory with a few things you may not have known about her lifelong love affair with (wo)man’s best friend.

Edith Wharton’s house has a dog cemetery

The Mount, Wharton’s home in Lenox, Massachusetts, features a pet cemetery with six little gravestones on a wooded knoll, marking the graves of Mimi (d. January 1902), Toto (d. November 18, 1904), Miza (d. January 12, 1906), and Jules (d. 1907), four of the dozens of dogs Wharton had over her lifetime. Wharton could see the cemetery from her window as she wrote (every day until at least 11, lying in bed), surrounded by her living dogs and gazing out at her dead. Since Wharton’s death, numerous ghosts have been sighted at the Mount, including ghostly canines—a few of which have even been photographed by guests.

Edith Wharton wrote a doggie ghost story

Wharton wrote many stories, and even many ghost stories, but “Kerfol,” first published in Scribner’s in 1916, is the only one to revolve around dogs. “Kerfol” tells the story of a woman, Anne, accused of murdering her husband Yves—though according to Anne, it was the ghost dogs (the dogs she loved and he killed out of spite), who ripped him apart to avenge his cruelty towards her—dogs whose spirits still roam the estate years later. As one critic puts it:

Wharton makes her argument against the tyrannical treatment of wives by appealing to the twentieth-century sense of how animals should be treated: if readers recognize that Yves de Cornault’s behavior toward animals makes him a not-fully-moral being, they may see his treatment of Anne as part of the same vein of immorality. More subtly, Wharton suggests that Western culture devalues dogs as much as women, and to her, both oppressions are equally troubling.

Edith Wharton also wrote poetry about dogs

In 1920, she published a series of “Lyrical Epigrams” in the Yale Review, the first of which reads:

My little old dog:

A heart-beat

At my feet.

Edith Wharton was an animal activist

Both Wharton and her husband Teddy were founding members of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and were active in a campaign to outfit the New York City streets with drinking bowls for dogs. She also frequently hired a “dog-knitter” to make sweaters for her pets—though whether this counts as activism or oppression I can’t exactly say. You’d have to ask the dog in question whether he was cold.

Edith Wharton felt she could actually talk to her dogs

In her unpublished autobiographical essay Life & I, she wrote:

I always had a deep, instinctive understanding of animals, a yearning to hold them in my arms, a fierce desire to protect them against pain & cruelty. This feeling seemed to have its source in a curious sense of being somehow, myself, an intermediate creature between human beings & animals, & nearer, on the whole, to the furry tribes than to homo sapiens. I felt that I knew things about them—their sensations, desires & sensibilities—that other bipeds could not guess; & this seemed to lay on me the obligation to defend them against their human oppressors.

In 1937, when her favorite dog Linky died, Wharton wrote to William Royall Tyler that she had always “understood” what dogs “said.” “I have always been like that about dogs, ever since I was a baby. We really communicated with each other—& no one had such wise things to say as Linky.”

In an earlier diary entry, from the mid-1920s, she wrote:

I am secretly afraid of animals—of all animals except dogs, and even of some dogs. I think it is because of the Usness in their eyes, with the underlying Not-Usness which belies it, and is so tragic a reminder of the lost age when we human beings branched off and left them; left them to eternal inarticulateness and slavery. Why? their eyes seem to ask us.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.