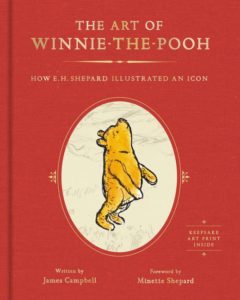

Some of the First Sketches of Winnie-the-Pooh

How a Honey-Loving Bear Revolutionized Children's Literature

The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

The four volumes known collectively as the Winnie-the-Pooh books divide into two books of verse (the first and third), and two books of stories about Pooh Bear and his friends in the Hundred Acre Wood (the second and fourth). At the time of publication, and for some years afterwards, the books of verse—which only included a few poems mentioning Winnie-the-Pooh—were more popular than the Pooh storybooks.

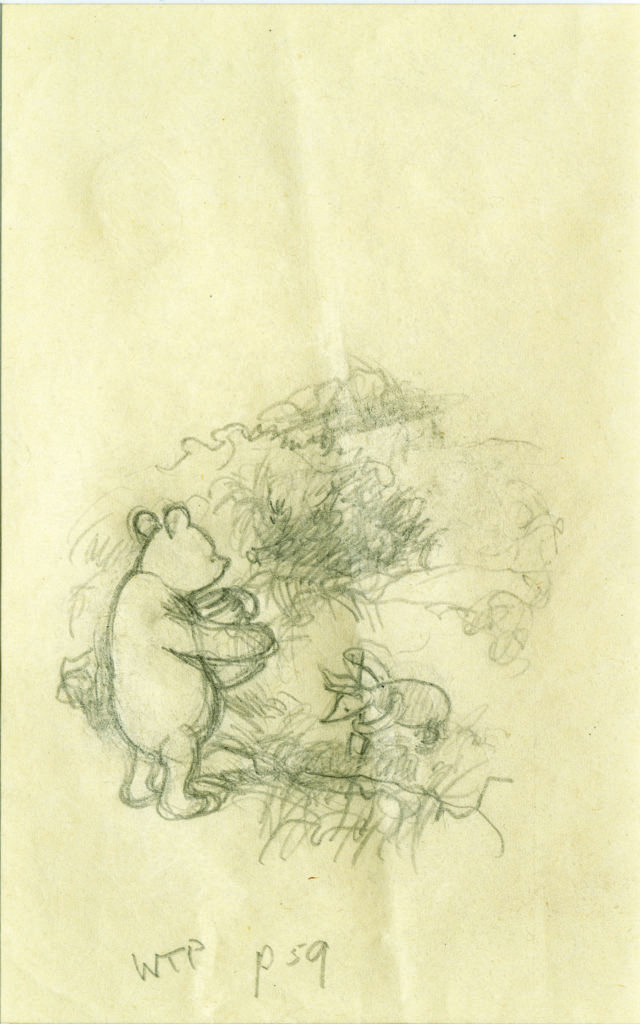

An early pencil drawing in which Pooh is holding a jar of honey while Piglet digs the Heffalump trap.

An early pencil drawing in which Pooh is holding a jar of honey while Piglet digs the Heffalump trap. The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

After the almost instantaneous success of When We Were Very Young, publishing house Methuen, Punch magazine, and the buying public were clamoring for more. E.V. Lucas (author and Chairman of the publishing house Methuen, who knew both A.A. Milne and E.H. Shepard through Punch magazine, and first suggested that Shepard should illustrate Milne’s work) had early on identified the teddy bear, who had featured in just three of the poems in the first collection, as being a potential focus for a sequel. Lucas knew that A.A. Milne already had some stories about Christopher Robin’s bear, which he had told his son in the nursery, and had a hunch that the bear had great potential, especially in view of the immense popularity of the real Winnie in London Zoo.

“At that time, such a collaboration between author and illustrator was relatively unusual.”

Lucas knew that Milne intended a further volume of verse (which would become Now We Are Six), but he felt that a book of prose stories featuring this bear would be very well received. Moreover, he was anxious that it be published with all due speed, so as to cash in on the enthusiasm for the first volume. Milne had written to Lucas saying, “I suspect that what you really want is that ‘Billy Book’ you have been urging me to write . . . Fear not. I will do it yet.” “Billy” was a reference to Christopher Robin, who was known in his early years as Billy Moon—Moon being his attempt to pronounce Milne. On December 24, 1925, in a story commissioned from Milne by the Evening News called “The Wrong Sort of Bees,” the name “Winnie-the-Pooh” first appeared. However, while Lucas and Methuen were extremely keen for this second book to go ahead, Milne did not intend to be rushed, as he had a number of other projects in hand, but he made it clear to E.H. Shepard that he would produce the book “in due course” and added, “In any case I shall want you to illustrate it.”

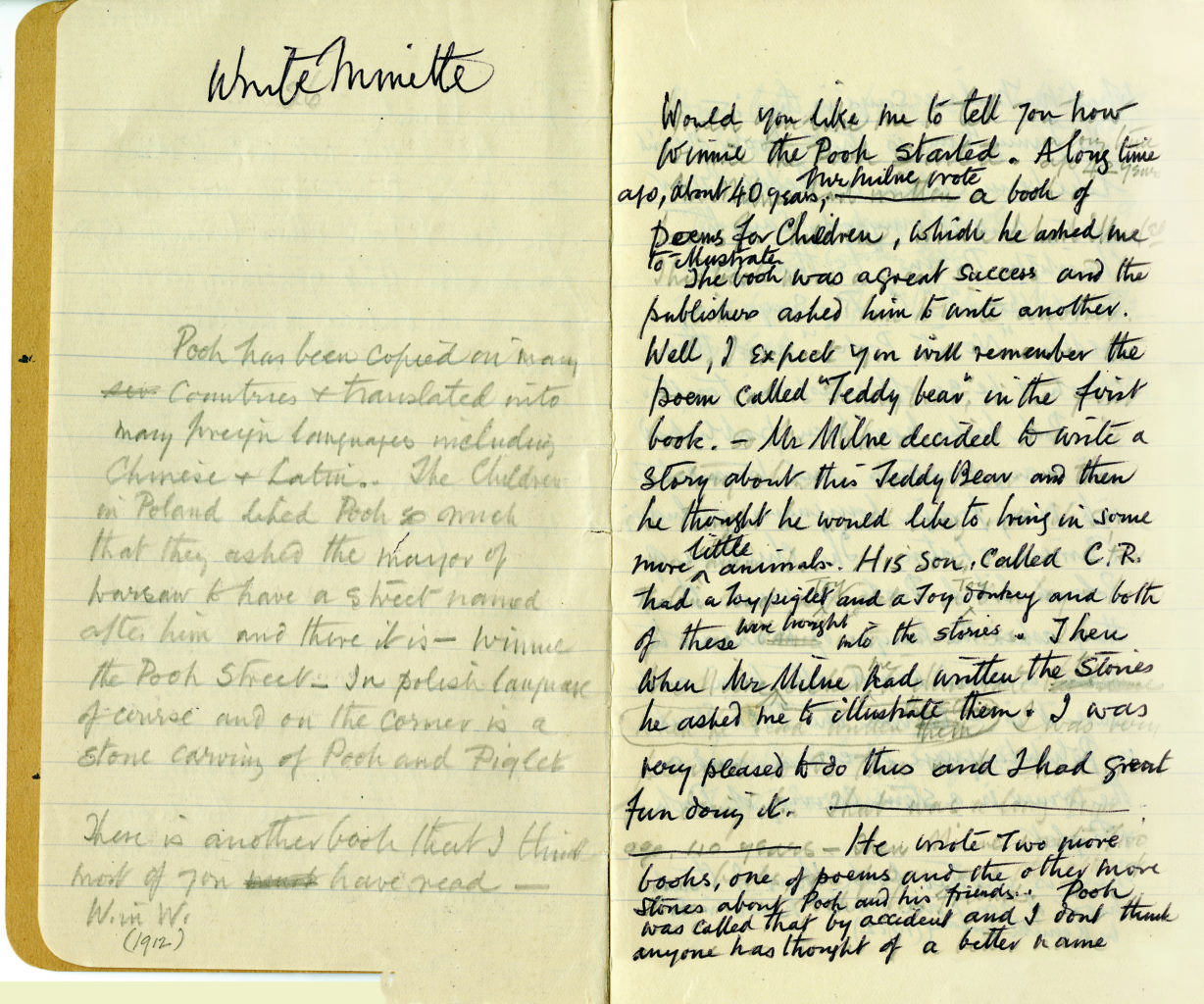

On this page from Shepard’s notebook (corrected and amended by him), he begins, “Would you like me to tell you how Winnie the Pooh started.” The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

On this page from Shepard’s notebook (corrected and amended by him), he begins, “Would you like me to tell you how Winnie the Pooh started.” The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

At that time, such a collaboration between author and illustrator was relatively unusual. Normal practice was for the publisher to determine the number of illustrations and their format as part of their commercial calculations when considering enhancing the sales potential of a book. Lucas had seen how successful the combining of text and illustrations had been, not only in Punch but also in When We Were Very Young, and this reinforced his view that this relatively groundbreaking approach would be one of the keys to the book’s success.

Milne also appreciated this, and decided to have Shepard involved at the earliest stages of his own creative process. For Shepard, this was moving a step further than when working on When We Were Very Young. Previously, he had been commissioned to illustrate the first 11 poems for Punch not only after they had been written, but also after some had already been illustrated by other artists. He had effectively been commissioned by Lucas, as publisher, and initially Milne had to be convinced. Once the poems were commissioned for book form, Shepard then worked around this format, but his relationship with Milne had always been generally reactive, as he followed instructions as to what was required of him.

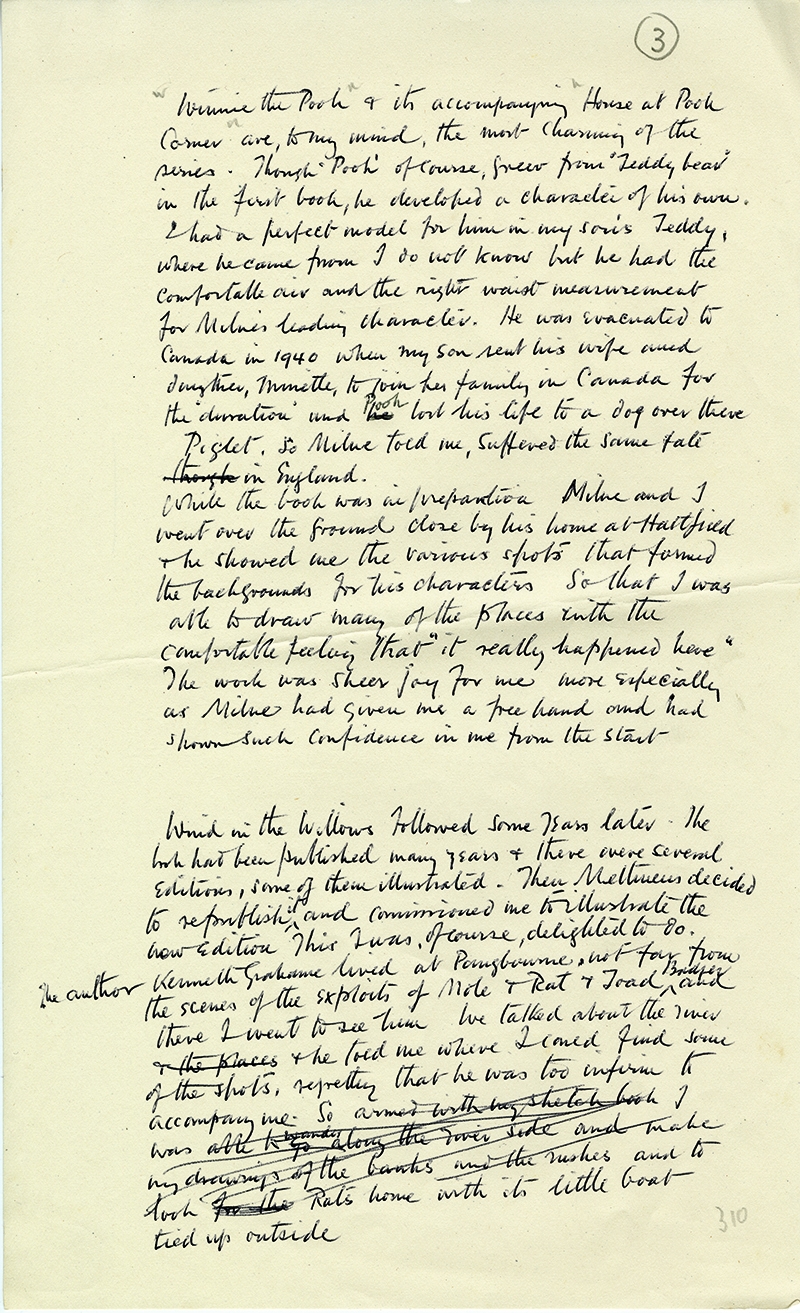

Shepard himself wrote in a draft of his memoir his own recollection of how his working relationship with Milne developed during the making of Winnie-the-Pooh, and of how the work was “sheer joy” as Milne had given him a “free hand,” which was, again, highly unusual for a book illustrator.

Shepard’s handwritten account of how Pooh developed a character of his own, and how he worked closely with Milne to ensure the backgrounds were as accurate as possible. The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

Shepard’s handwritten account of how Pooh developed a character of his own, and how he worked closely with Milne to ensure the backgrounds were as accurate as possible. The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

From now on the working relationship was to be proactive on both sides. While Shepard did virtually all his work in his studio in the garden at his home at Shamley Green, he generally went up to London to show and discuss his work. It seems likely that he met Milne at the offices of Methuen at 36 Essex Street, off the Strand, and on occasion at Milne’s London home on Mallord Street in Chelsea, which was almost certainly the setting for the staircase with the red carpet that features in “Halfway Down” in When We Were Very Young, and as the very first illustration in Winnie-the-Pooh.

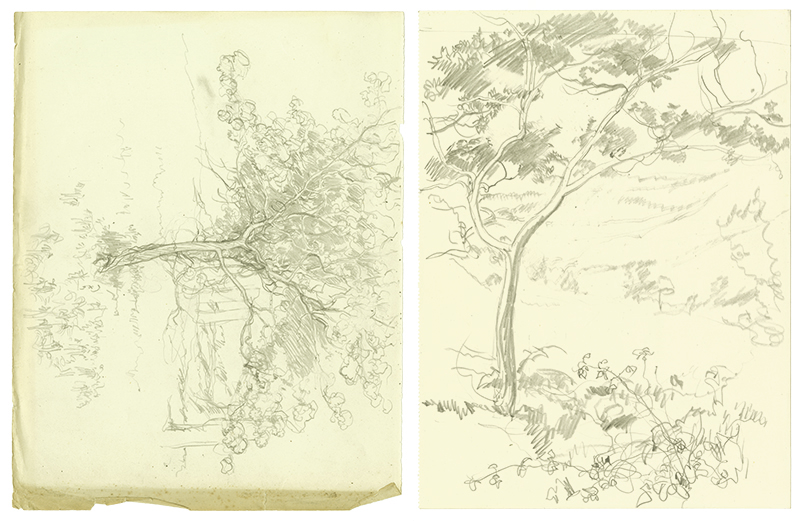

These two sketches of trees are very typical of Shepard’s approach. There are hundreds of similar sketches of trees and landscapes from around the Ashdown Forest, and he used these extensively in creating accurate backgrounds. The Shepard Trust.

These two sketches of trees are very typical of Shepard’s approach. There are hundreds of similar sketches of trees and landscapes from around the Ashdown Forest, and he used these extensively in creating accurate backgrounds. The Shepard Trust.

The Milnes had also recently acquired a country home, Cotchford Farm near Hartfield, a picturesque village by the Ashdown Forest in Sussex, principally used for weekend visits, which allowed Christopher Robin more space to play outside, with the inviting prospect of the forest immediately to hand. At Milne’s suggestion, Shepard made several visits there in 1925 and 1926, driving over from Shamley Green to check the scenery and topography as described by Milne, who showed him the specific locations for each story. Shepard’s preliminary drawings and sketches show the extraordinary attention to detail that he paid to the supposedly fictitious Hundred Acre Wood, and reveal the beauty of its real-world counterpart, Ashdown Forest’s Five Hundred Acre Wood.

Shepard always worked hard on his research and continued to spend much time in and around the Ashdown Forest, paying particular attention to the stands of trees and the general vegetation. Indeed, it is often remarked that on occasion it looks as though he created careful and representative landscapes into which he inserted sometimes cartoon-like characters.

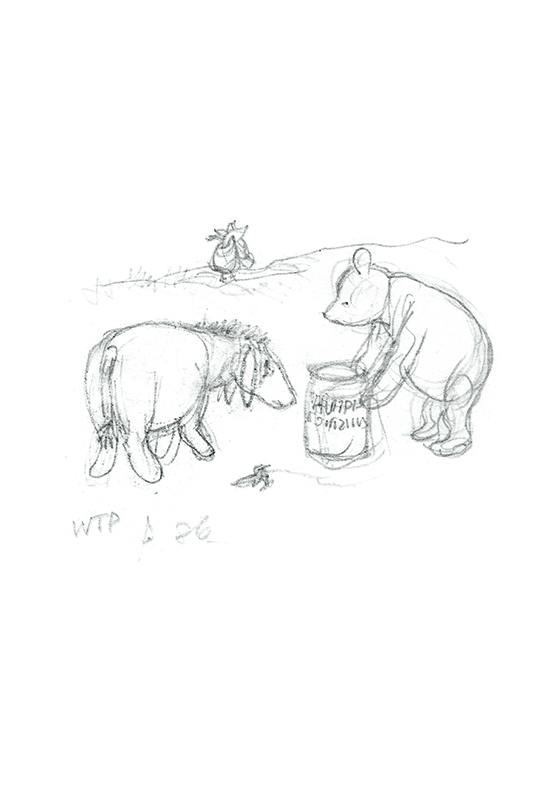

This drawing, a preliminary for the scene in Chapter 6, where Eeyore receives an empty jar of honey from Pooh, shows how in just a few strokes of the pencil Shepard creates a sense of movement, with Eeyore sniffing at the jar and Pooh looking anxious as it is empty. Is that Piglet on the horizon? The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

This drawing, a preliminary for the scene in Chapter 6, where Eeyore receives an empty jar of honey from Pooh, shows how in just a few strokes of the pencil Shepard creates a sense of movement, with Eeyore sniffing at the jar and Pooh looking anxious as it is empty. Is that Piglet on the horizon? The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

Winnie-the-Pooh was obviously all about Pooh, and Shepard drew heavily on his own son Graham’s teddy bear Growler for inspiration to create the marvelous images of a larger-than-life character, stuffed full of human traits and foibles. One original drawing which Shepard kept for himself was the picture of Winnie-the-Pooh standing on tiptoes on a chair to reach a jar of honey. The other characters were introduced chapter by chapter, so that we meet Winnie-the-Pooh in Chapter 1, Rabbit in Chapter 2, Piglet in Chapter 3, Eeyore in Chapter 4, and so on. Shepard used toys from Christopher Robin’s nursery, many bought from Harrods and some, later, purchased specifically for the purpose, to create Piglet, Eeyore, Kanga, and Roo. Owl and Rabbit (and all Rabbit’s “friends and relations”) were from Milne’s imagination and not based on any real-life toys, and so Shepard had to use his own creative talents to bring these characters to life. Shepard continued to use his sketches of Graham as a young boy as the basis for the drawings of Christopher Robin, sometimes marrying these with images of the real Christopher Robin. He drew sketch after preparatory sketch, working to get exactly the right image to illustrate the correct part of the story, and in response to Milne’s and Methuen’s reactions.

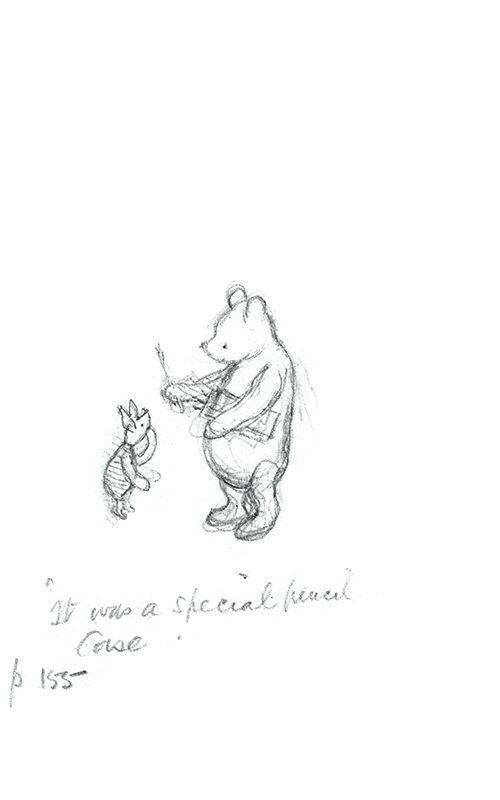

A pencil sketch captioned by Shepard “It was a special pencil case”—note the resemblance of Pooh to the very earliest sketch.

A pencil sketch captioned by Shepard “It was a special pencil case”—note the resemblance of Pooh to the very earliest sketch. The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

Winnie-the-Pooh was published in London on October 14, 1926—and in New York on October 21—to even greater acclaim. In the UK, Methuen’s first print run totaled 32,000 this time, and entirely justified Lucas’s optimism, while in America 150,000 copies had been sold by the end of the year. The book was immediately reprinted and, of course, has never been out of print. Clearly on the crest of a wave of critical and commercial success, Lucas once more urged Milne and Shepard forward towards book number three.

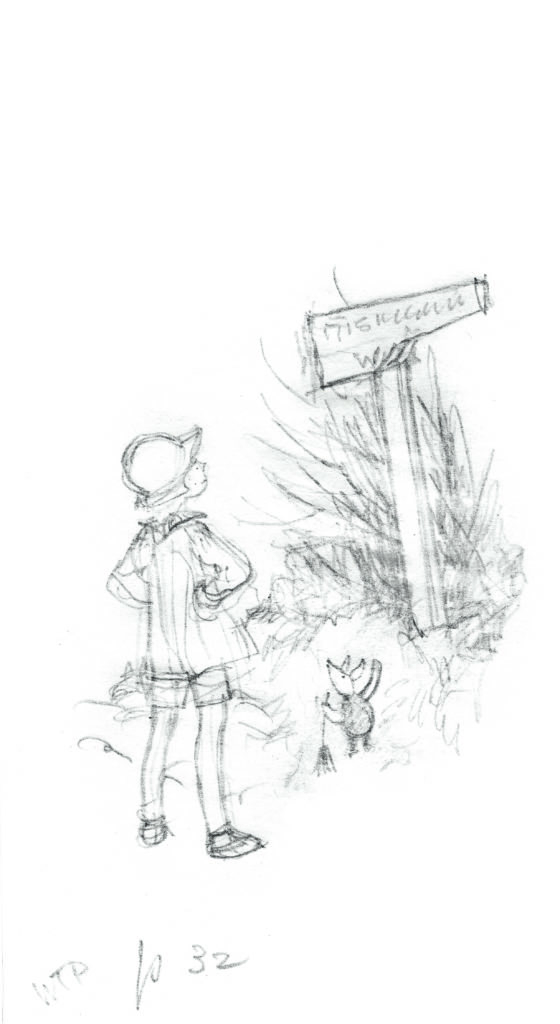

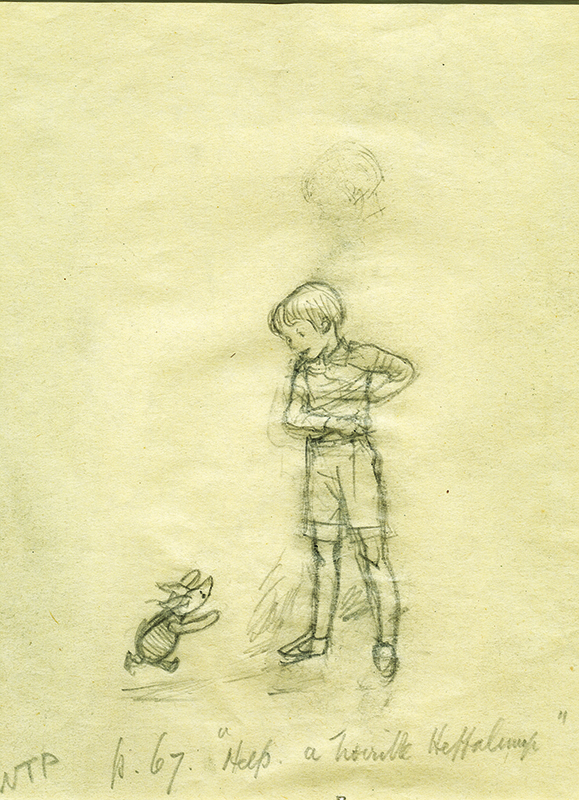

An early pencil version of Piglet running toward Christopher Robin crying out “Help a horrible Heffalump.”

An early pencil version of Piglet running toward Christopher Robin crying out “Help a horrible Heffalump.” The E.H. Shepard Archive, University of Surrey.

Shepard and Milne had torn up the rulebook and made the public look at literature, and particularly children’s literature, in a different way. Rather than reading to children, the books inspired authors and illustrators to write for children, and in the period up to the Second World War, this opportunity for adults and children to sit and enjoy books together grew rapidly. The Story of Babar was first published in 1931, and Orlando the Marmalade Cat in 1938, both following this model of stories that integrated words and pictures in a seamless format.

__________________________________

From The Art of Winnie-the-Pooh: How E. H. Shepard Illustrated an Icon. Used with permission of HarperCollins. Copyright © 2018 by James Campbell.

James Campbell

James Campbell has worked for a number of sustainability and environmental organizations for more than twenty years. He is married to E.H. Shepard’s great-granddaughter and has had responsibility for the oversight of E.H. Shepard’s artistic and literary estate since 2010. Hi is the author of The Art of Winnie-the-Pooh. He currently lives in Oxford, England.