So You've Decided to Write: When to Drown Your Darlings

Part Two in Terry McDonell's Summer Series on How to Be a Writer

Another editor, a rival of mine with a fondness for hypocrisy, once said there was nothing worse than a truthless writer, but I have never known any. I know some whose writing has too much style and not enough story, but their lives are never like that. The writers I know make their lives more interesting just by being writers—which is not the same as writing, but that divergence leads to self-serving distinctions good writers never care about anyway. Let’s just acknowledge that writing is hard so it is okay to be a little tortured, and some writers are. It can all go very dark, but there is no sweeter validation than getting published for the first time. I sometimes remind writers of that. You can remind yourself.

Good editors, like doctors, develop a bedside manner. My editing was full of questions—all the same question, really. What is the story? What’s the point of it? What do these sentences mean? Do they mean what you want them to mean? What if I told you they read like walk-ons in a Pirandello play?

To diagnose is an excellent verb for editors to keep in mind. But then, “What are you trying to say?” is not always an easy question, and the story isn’t always what the writer says it is. My point here is that it always helps to get right to the point. As the great Esquire editor Byron Dobell liked to put it, “If you’re going to write about a bear, bring on the bear!”

Writers’ block? I want to make quick work of this. As an editor I insisted there was no such thing. Writers could fight through it if they just kept working. If they complained, I’d quote Gloria Steinem: “I do not like to write—I like to have written.”

This does not mean editors should be unsympathetic. No one likes to be called “The Stonecutter,” as the excellent writer-editor David Felton was by his colleagues at Rolling Stone, which was a tough place way back when it was humming with good writing. Besides, careful writers were always worth waiting for, and speed often rides with carelessness. Writing well is just hard, and every good writer or editor I have ever known could empathize with that.

For years there was no finer writer at Rolling Stone than Kurt Loder, who wrote very slowly but with great facility before moving on to anchor MTV News. When I asked him if he missed writing he said, “You have to be kidding.”

What do your sentences mean? Do they mean what you want them to mean? What if I told you they read like walk-ons in a Pirandello play?

Editing is about ideas, but it is mechanical, too. You have to get under the hood of the language, and editors use many tools. Some are clichés but you should still avoid them like the plague, no matter how amazing or incredible or unbelievable or challenging it can be to raise the bar—even when you are writing about icons ideating on the brand message; and never circle back.

Likewise it is prudent to take Kurt Vonnegut’s advice: “Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you’ve been to college.”

Think like Mark Twain: “When you catch an adjective, kill it.”

As you build robust and rangy vocabulary you will also develop an ear for debased language. This is closely related to “kill your darlings” which means cut anything precious, overly clever or self-indulgent. Curiously this stark, brilliant prohibition is attributed most often to William Faulkner but also to Allen Ginsberg, Oscar Wilde, Eudora Welty, G.K. Chesterton, Anton Chekhov and Stephen King, who used the phrase in his effusive On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft: “Kill your darlings, kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.”

When the 2013 biopic of Allen Ginsberg, Kill Your Darlings, came out, Forrest Wickman on Slate tracked what is probably the best attribution to Arthur Quiller-Couch in his 1914 Cambridge lecture “On Style.” The prolific poet, novelist and critic railed against “extraneous Ornament” and emphasized, “If you here require a practical rule of me, I will present you with this: ‘Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally new writing, obey it—wholeheartedly—and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.’”

Wickman’s research also brought him to an even more important rule for journalists: “Check your sources.”

__________________________________

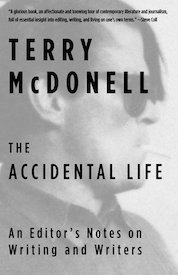

Adapted from The Accidental Life: An Editor’s Notes on Writing and Writers, by Terry McDonell (who is a cofounder of this website), published this month by Vintage. TerryMcDonell.com.

Terry McDonell

Terry McDonell has published widely as a journalist, top-edited a number of magazines, and was elected to the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame in 2012. He is the author of The Accidental Life: A Editor's Notes on Writing and Writers and Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son. He is president emeritus of the Paris Review Foundation and co-founder of Literary Hub. TerryMcDonell.com