So You've Decided to Write: What I Learned From Editing Jim Harrison

Part Three of Terry McDonell's Summer Series on Becoming a Writer

The first chapter of Jim Harrison’s first novel, Wolf, begins with a two-page, 412-word sentence. He would say it was vanity, and that he wanted to show it could be done because he was a young writer and hungry. When I was starting to work with him, I asked if his editor had tried to do something with that first sentence.

“Of course,” he said wearily, as if in my tragic inexperience I was unable to grasp the basic construct of editing him. Jim did little revising and was proud of it. Rewriting was for people who hadn’t worked everything out early—not for Jim, who insisted that he always thought things through before he wrote anything down. As for editors, why should he let them fool with his choices? They were not, as he had explained to me when we first met, writers. He also liked to note that he was a poet and “editors don’t change poems.”

“I wouldn’t change any of your poems either,” I said, but when it came to his journalism I wasn’t so sure, and we tangled over copy our first time around. I was at Outside magazine and suggested that his lede on a story about Key West was really the second paragraph and the first paragraph should be the kicker. He hung up on me.

I got an immediate follow-up call from his agent, Bob Dattila, a tough, reasonable guy.

“You want to pull the piece?” I asked, after his declension of my shortcomings.

“Of course not,” Dattila said. “We just want to be on the record about what a dumb shit you are.” (Pause.) “Jim can be difficult, too.”

“So we’ll all think about it?” I said.

“Exactly.”

I’m not sure how much we all thought about it, but I switched the paragraphs and we never discussed the piece again. Maybe Jim didn’t notice. But I learned to tread lightly or risk being told, as I once was by him, “You lynched my baby.” His raw copy was so ambitious that I usually just checked the copy edit and wrote the headline. We talked about other things, like what we were having for dinner.

“I learned to tread lightly or risk being told, as I once was by him, ‘You lynched my baby…’”

Jim lived on a farm in Lake Leelanau, Michigan, 50 miles from where he was born. There was also a cabin on 60 acres off a two-track road five hours north by car, on the Upper Peninsula, where he sometimes retreated to write. But Jim could write anywhere, and he did.

Some writers set themselves up so they could work with a view—the mountains, the sea, a river, perhaps an interesting cityscape. Others worked closed-in, with no distractions, just their desk and whatever they had on the wall in front of them. Jim was like that, working best from two to four in the afternoon in tight places like the one-room ranch cabin with small windows and a calendar 20 years out of date on the back of the door.

This was the winter place in Patagonia, Arizona, that Jim’s early screenwriting money had paid for. A journalist sent from New York to interview him had walked with Jim the half mile from the main house to his writing cabin and asked if it was a movie set. This turned into a story Jim would tell about what he saw as the misunderstanding about his work because no, he wasn’t in the movie business. Not really, anyway.

Jim’s novellas were heroic, in what Jim called “an oracular style.” That’s what sold to the movies—or, rather, to the specific people in the movie business who wanted to work with Jim. Not just Jack Nicholson but producers and directors like John Huston and Mike Nichols. The list was long and Jim was proud of it, and I think everyone Jim knew in the movie business got something memorable from him, something personal, a little bit of poetry like the story he sometimes told over steak dinners about the most devout girl in his youth Bible group having “the feral odor of a butcher shop to go with her great beauty.”

Jim kept up a wide and eccentric correspondence begun, in some cases, when he was a teenager writing confidently to literary figures that had not yet heard of him, like the esteemed poet and Dante translator John Ciardi. In his letters to me I saw phrases and ideas (about say food or bird watching or a waitress he liked) that would arrive again in filed copy as I edited Jim at various magazines from Rolling Stone to Esquire to Sports Illustrated. When I left magazines we stayed in touch partially because I had become one of his “Poetry Friends.”

Jim wrote his poems longhand, faxed them to his assistant in Lake Leelanau, where she would type them over and send back for him to make changes. When he was satisfied, she would email them to Jim’s list, which was approaching 25 or so when he put me on it.

Many of the poems were about death. In “Time,” he wrote that it (time) was withering him, but with a galactic smile. Jim said the poems descended on him, and by this time he was working shirtless because of severe shingles. He wrote a poem titled “Barebacked Writer” about two years of postherpetic neuralgia, where the pain is always present. I wrote Jim that the pain must be on the edge of unbearable, though I was moved by the poem. Jim wrote back advising me to retire to the arts.

“We just want to be on the record about what a dumb shit you are.” (Pause.) “Jim can be difficult, too.”

Before I edited Jim, I had read Wolf several times. In it Jim wrote: Perhaps I’ll never see a wolf. And I don’t offer this little problem as central to anyone but myself. Fair enough. As a reader, I took that as a glance at a private mystery. Then, as a young editor, I wanted that wolf to be my problem, too. I wanted to ride along. I hoped that was how I could become a good editor, by editing writers like Jim and getting to know them.

When I heard that “Mozart de Prairie” was the headline of a story about him on the arts front page of Le Monde, I looked for it and found many pieces in French newspapers about him but none with that headline. Maybe it was apocryphal. If it had run, I hoped the photo was the one of Jim as a young poet in overalls without a shirt underneath, leaning back with his arms spread across the side of a farm horse. Jim became famous for his diction, celebrated internationally as a storyteller of genius, but over all the years and the novels and novellas and the films that came with them, he remained a poet, his life syncopated with complexities and the chromatic cadences of rural landscapes. “Mozart de Prairie” was a brilliant headline, even if it never ran.

__________________________________

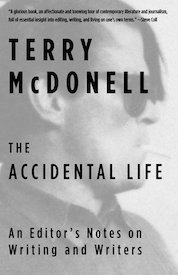

Adapted from The Accidental Life: An Editor’s Notes on Writing and Writers, by Terry McDonell (who is a cofounder of this website), published this month by Vintage. TerryMcDonell.com.

Terry McDonell

Terry McDonell has published widely as a journalist, top-edited a number of magazines, and was elected to the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame in 2012. He is the author of The Accidental Life: A Editor's Notes on Writing and Writers and Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son. He is president emeritus of the Paris Review Foundation and co-founder of Literary Hub. TerryMcDonell.com