Snapshots Before the War: Saying Goodbye in 1944

Paul Hendrickson on the Day His Father Shipped Off to Japan

I am looking at a faded page from my broken-backed baby book.

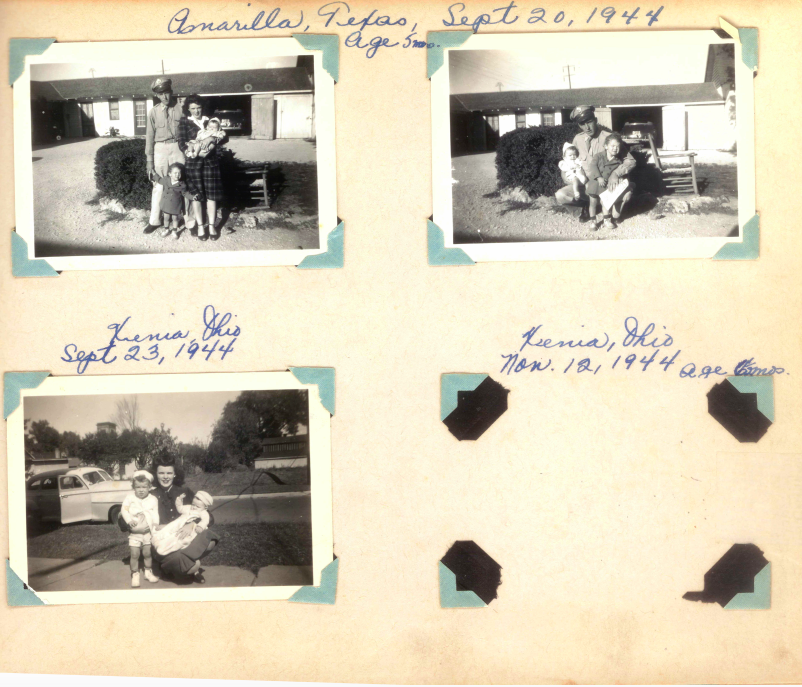

On September 20, 1944, at about nine in the morning, two farm kids from Ohio and Kentucky told each other goodbye out front of a sad-sack-looking motor court in Amarillo, Texas. Perhaps the only thing extraordinary about the moment was how ordinary it was to its time and place. They were my parents, and they are dead now. No matter what else I might ambivalently say about what turned out to be their largely sorrowful 61-year marriage, this part of their story seems to me absolutely good, even heroic.

I have been thinking about this parting moment a lot lately for too-obvious reasons: the idea of terrifying things swirling invisibly about you and over which you seem to have only limited control.

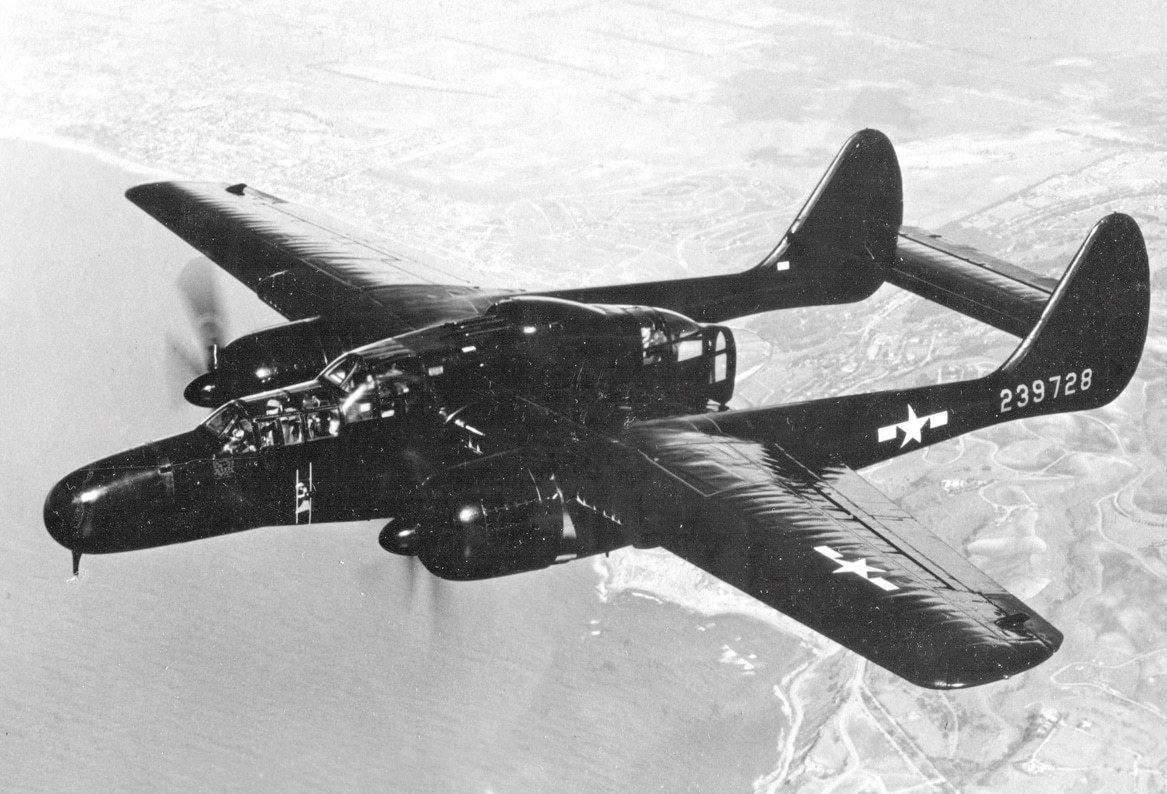

My first lieutenant dad, 25, pilot of a P-61 Black Widow, was leaving for the war. He was headed with his night fighter squadron to the Western Pacific, to Iwo Jima. The 549th Night Fighter Squadron of the Seventh Air Force didn’t have its announced orders yet, but the rumor in the ranks among the squadron’s nearly 300 officers and enlisted men was that they were going to the Pacific Theater. The specific destination, which they wouldn’t get to for a few more months (there would first be an outfitting and training stay in Hawaii, and then some less scary mission duty on Saipan), turned out to be that iconic scrap of sulfurous sand, 760 miles from Tokyo, which my father, for the rest of his life, whenever he spoke of the war and his time in it, simply referred to as “Iwo.”

He arrived on Iwo in a convoy of Widows in the third week of March 1945, a little less than a month after the Marines had immortally raised the flag on the summit of Mount Suribachi in the Battle of Iwo Jima. One of the bloodiest and dirtiest and costliest sieges in all of World War II.

For the next five and a half months, belted into his cockpit of glowing knobs and dials, my father flew approximately 75 combat air patrol missions, roughly 175 hours of logged time, the bulk of it at night, off of what was named South Field on Iwo. His type of aircraft was a sleek and lethal thing, poisonous as the spider from which she’d taken her name, a combination fighter-bomber, a pursuit ship, from the Northrup Aircraft Corporation, with a twin boom tail design and with a small crew of three: lone pilot, radar operator, gunner. She was the first operational warplane of World War II to have been built specifically as a night fighter, powered by her Double Wasp 18-cylinder engines and armed with her 50-caliber machine guns and 20-millimeter cannons and a 360-degree rotating dorsal gun turret and, not least, armed with a state-of-the art radar detection equipment sealed in her nose.

Photo via Paul Hendrickson

Photo via Paul Hendrickson

Like my dad, the Black Widow was coming very late into the war, at least into the shooting war, but she carried an undeniable mystique. I think it had to do with the idea of dark, of stealth, of working under cloud cover or in the glow of moonlight. “Fighting the night,” I’ve heard my father call it, with the poetry of which he was often unconsciously capable. I have his old flight records now as well as a two-inch stack of other documents that were in his military file at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis. (There was a giant fire there in 1973, but somehow my dad’s entire military service record was saved.) I am also in the process of acquiring his individual mission reports from Iwo. I can’t wait to get my hands on those. They’re in a different repository, in Alabama. I can’t go there at the moment, but I will eventually. For so many reasons, I am terribly saddened that my dad is gone, and not least because I can’t ask him—selfishly—all I long to know, as a journalist, as a son, about sultry days on Iwo and freezing nights at 10,000 feet and so many other aspects of the war that no amount of documentary record, regardless of how rich, could ever impart. It’s true I got him to talk about some of it in the years before he died, but never for long enough.

“You just grabbed somebody in maintenance and said, ‘Listen, I want you to put my wife’s name on my airplane and make it beautiful.’ And the guy would have snapped to and said, ‘Yessir, Lieutenant.’”

Once, I got to accompany him to a night fighter’s convention in Orlando where I met some of his old squadron mates. That was in the 80s, four decades after Iwo. If a lot of it was paunchy old men drinking a little too much and telling their mythologized war stories, that’s not all it was. “You can’t imagine how happy I was to hear your old man was going to be here,” somebody said, collaring me close, whispering it in my ear. I could hear the choke in his voice. It was the last night, at the big banquet. The speeches were going on way too long. The AC wasn’t working very well. When my dad and I tried to slip out early, the same collaring voice issued a command: “Help your dad with that coat!”

I have all those pages of yellowing notes from that reunion, but in another sense they’re still just notes. What I really long to hear is my father’s voice. He’d be 102 if he were alive. I’ve got just one old scratchy cassette tape, and what he says on it isn’t even about the war.

“Really, I didn’t do all that much in the war, Paul,” he once said.

“But you were there, dad.”

“Yes, I suppose that’s so.”

*

The leaving, the going. With the same craving, almost a carnal craving, to know more, I find myself staring at a couple of old snapshots that my archival-minded mom so lovingly and carefully glued into my baby book three quarters of a century ago. Here we are, our neophyte family of four, about to be separated as a nuclear unit, and who knows if forever, with two of the parties in the frame having no idea as to what is really going on.

Image via Paul Hendrickson

Image via Paul Hendrickson

My mom is only 21 and has already brought two babies into the world. I am the not-quite-five-month-old protected in her left arm and with part of her right. That’s my squirmy older brother Marty between my parents. He’s 21 months old. Like my parents, he’s also gone. It was such a hard life, a mostly failed life, enough of it of his own making, to my mother’s constant sorrow and to my father’s, often enough, violent anger. When Marty was dying a few years ago in the hospice unit of a Veteran’s Administration Hospital at Bay Pines, Florida, we listened to a lot of Tom Petty (“I Won’t Back Down”) and spent some time in between talking about how angry my father seemed in the late 40s and all through the 50s, when the two of us were growing up, trying to outrun his wrath. There wasn’t recrimination in our talk so much as love, an increasing depth of understanding. I’m able to see much more clearly now that my father must have come home from the war with PTSD and didn’t know how to escape it except to take it out savagely on his sons’ backs with his belt, which he’d peel right off his pants. Sometimes he went after us with boards he retrieved from the basement. In our childhood, Marty and I used to take nighttime baths together, sitting in the tub comparing our welts. Is it any wonder we both fled as teenagers into the same Catholic preparatory seminary? But all that’s another story, or at least not the story for here.

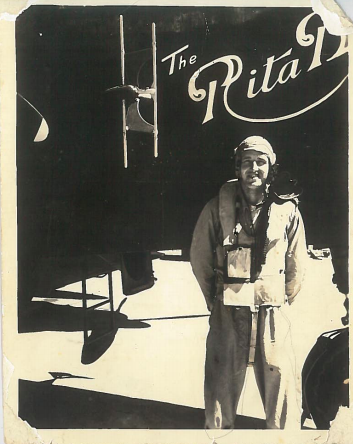

My mom’s name is Rita. Her middle name’s Bernardine. Not too long removed from this Amarillo moment, in a far Pacific place, the words “The Rita B” are going to get artfully scrolled in curvy white on the glossy black tubular nose of my father’s P-61. I asked my dad once who did the paint job on The Rita B.

“Damned if I remember, Paul. You just grabbed somebody in maintenance and said, ‘Listen, I want you to put my wife’s name on my airplane and make it beautiful.’ And the guy would have snapped to and said, ‘Yessir, Lieutenant.’”

I have another picture that I treasure. It’s of my father grinning in front of the spanking art work. He’s in his flying suit and inflatable Mae West life preserver and unbuckled oxygen mask and skin-tight leather aviator’s cap. The big black machine is hovering above him, casting its shadows in dark slashing angles on the blinding white tarmac. It almost looks like a modernist painting, maybe something Edward Hopper would have tried at his easel if he took a sudden whim to monochrome. On the back of the picture, one corner of which is torn off, are these barely legible words: “How do you like my plane’s name?” I’d bet anything he wrote the message and immediately posted the picture to the states.

When Marty and I were kids we were so proud that our dad was an aviator. I have written in another place of how we used to brag to our classmates on the playground that he could fly the crates the planes came in. I think that’s a line from a Cagney movie.

Rita B. has gotten up this morning and put on her smart Scotch-plaid suit and sling-back pumps, has combed out her thick Irish coils of raven hair. She’s ready for the day, or at least is pretending so. I wonder what this motel set them back last night—five bucks? And did they get any sleep? And were we all in one bed? And was there some attempt at silent lovemaking once Marty and I were finally down for the night? How could there not have been?

I said they were two farm kids out of Ohio and Kentucky. My mom’s farm town was and is a little place called Xenia, which is in southwestern Ohio, not far from Dayton. (It’s pronounced Zeen-ya.) The land there is rich and black and rolling and loamy. Both my parents are buried in Xenia, and Marty too, and a stillborn sibling named David, and about two dozen other extended family members on my mom’s side. Xenia is where Rita B. is headed today, perhaps pulling out in the next 30 minutes. She and another Army Air Forces wife named Edy Kessler (her husband Charles, a pal of my dad, fellow 549ther, is also going to Iwo in his Black Widow) will shortly get into my parents’ car, with Marty and me in tow, and drive across the rest of the Texas Panhandle, and into Oklahoma, and up into Missouri, and through Illinois, and then across Indiana, and finally into Ohio, something like 1,100 miles in a little less than four days. Two wartime women, barely out of their teens, on those bumpy two-lane wartime roads, already heartsick from missing their men, and overtired too, with Marty and I squalling in the car, with my mom and Edy heating up the Gerber’s strained peas on hot plates at night in the motel rooms, both of them reading the road maps and checking the oil and refueling at the gas stations, obeying the wartime restrictions on speed limits, changing the poop-filled cloth diapers and searching on the floor of the car for the talc and safety pins—all of this and more. For all that I have thought about what my father faced in the war, I know I am guilty of not considering enough, not nearly, of what my mother did in the war, what all our mothers had to do in their own shouldering ways and circumstances. Oh, yes, I should add: Edy Kessler was several months pregnant. So I wonder if she wasn’t fighting motion sickness and morning sickness all the way across. Her family lived in Teaneck, New Jersey. That’s where she intended to wait out the war through her fear and prayers. My mom was going to wait it out in her fear and prayers in Xenia, at 8 Mechanic Street, in the home of her mother and father, whom I could only think of throughout all my childhood as “Pop” and “Nonna.” Pop was my substitute father while my father was overseas. Pop was a corn and soybean farmer, who’d been too old for the war.

*

The story of how my parents arrived at their going-away moment in a scuffed-dirt motel courtyard at the back end of the war starts with Xenia. I know some of this must begin to sound like the script of a Hollywood B-movie produced especially for the war effort, but it’s a true fact, however cliché and Frank Capra-seeming, that my parents had bumped into each other, almost literally, at a Xenia roller rink on a Friday night three-and-a-half years before. I can’t swear that the rollerdrome’s organist had risen out of the floor to pump “Lady of Spain, I Adore You,” just as my mom twirled in her chaste tights and lace-up skates past the good-looking soldier boy—I only like to think so.

This would have been in the early part of 1941, ten or eleven months before Pearl Harbor. Everything was so speeded up then. America wasn’t in the war yet, but who didn’t know it was coming? Rita B. was still in high school then. Rita B. would have been either 17 or 18 then. (Her birthday is in early February.) Rita B. was angling for the lead, in that spring’s senior-high production at St. Brigid’s Catholic High School, of a comedy farce called “Peggy Parks.” (She’d get it, too, and the Xenia Evening Gazette would report that she “gave a splendid performance and made a nice stage appearance.”) Rita B. had a size 16 waist. Rita B., even (or especially) then, knew how to work her wiles, her will, and not just on males.

And the lank soldier boy, who was four years older? He was over with a buddy from Patterson Field in nearby Fairfield, Ohio. Almost certainly he was in uniform, the better to snag the glances of the local girls. He had a hot-looking convertible and a staff sergeant’s stripes on the sleeve of his Army Air Corps blouse. He was off a sharecropper’s farm in Morganfield, Kentucky, third-born in a Depression family of nine. He went by two first names, and for all I know he probably wondered why the rest of the world didn’t go by two as well. He introduced himself to people as Joe Paul Hendrickson, and the way it came out of his mouth was the way it had always come out back on the farm in western Kentucky, as if it were really one name, one word: Joepaul. (After the war, when he hired on with Eastern Airlines, co-piloting DC-3s out of Midway Airport in Chicago, he would gradually drop his second first name; it was as if he had begun to Yankee-fy himself, at least in superficial ways.)

The soldier boy, with his farmer’s blunt hands, with his cocky grin, had a small vertical divot that came down the middle of his chin and that was destined to get more pronounced in the years up ahead. The soldier boy, who had been able to go only to high school before his enlistment in the Army Air Corps in 1937, could slide into metaphor without truly understanding what a metaphor was. (“We’d better get out of here before a fire starts licking at our boots,” he’d be apt to say if he were sitting in the balcony of a picture show and suddenly smelled smoke curling up from below.) If he weighed one hundred and thirty-five then, it must have been partly due to a couple of wrenches in his back pocket. At this stage he was still working under the hood of the big throbbing things instead of being able to strap on a parachute and climb inside their cockpits and take them up into the sky. It wouldn’t always be like this, he’d promised himself—and possibly the high school girl at the skating rink that night, too. One way or another, he was going to get into flight school. He was going to become an officer, an aviation cadet. Actually, when they met, he wasn’t really a lowly grease monkey any longer. He’d been a mechanic crew chief for a couple of years, supervising the other grease monkeys. Still, the gleam in his flying eye had yet to be realized.

I’d give a lot to know what my parents said to each other there at the Amarillo last. And I never got around to asking.

The Capraesque newsreel, the forties cliché in sepia: the staff sergeant from the local air base and the newly graduated schoolgirl were spooning at a double feature in a Xenia movie theater (I can’t promise it was the balcony) on a Sunday afternoon in early December of that same year, 1941, when the house lights went suddenly up and the panic-stricken manager ran down the aisle to cry that the Japanese had just attacked America. I heard this story a lot in my childhood—well, okay, not the spooning part. But I take the essence of it to be true. My parents’ generation could remember precisely where they were when they first heard about Pearl Harbor in the way my generation can remember exactly where we were on November 22, 1963.

Sped up? They got married two months later. It was a high mass on a Tuesday morning at St. Brigid’s. Father Schumacher officiated. The newlyweds left for a two-night honeymoon in nearby Richmond, Indiana. (Gazette: “The bride’s going away costume was an aqua crepe ensemble, with which she wore navy accessories, and a corsage of gardenias and violets.”) The next month, March, my dad burned through three or four noncommissioned ranks and then took the oath of office for a wartime officer’s commission. For the next 30 months they lived in 14 towns and cities, one field or base or depot after another. “We left Xenia on March 23, 1942,” my mother once told me. “Every two months the government was transferring us somewhere else.” She ticked them all off for me, and I scribbled them down in my journal, and damn if she didn’t have them in the precise sequence, by almost the exact dates, as I’ve lately discovered from pouring over my dad’s military records.

It was out to San Bernardino (San Berdoo, I remember them speaking of it in my childhood, as if they had an insider’s knowledge of the cool way to say it) and, no sooner having arrived in California, it was back East, to Hartford, Connecticut, for some TDY (temporary duty) schooling at a Pratt & Whitney aircraft engine factory. They crisscrossed the country by Pullman train and Greyhound and, sometimes, in their own car.

When it was by automobile, they rolled into the next place with their two sticks of furniture and their wedding gifts (at least the useful ones, like pots and pans) and rousted up some cheap military housing. Santa Ana, Bakersfield, Glendale (Marty was born there, in next-door Phoenix, at the end of 1942), Yuma (where my dad got his wings), La Junta, Orlando, Kissimmee, Ocala, El Centro, Fresno—I haven’t said them all, and not in the right order, but you get the idea: their own blurring gazetteer of America. Two rural kids from the Midwest and the border South experiencing the continent, one coast to another, the great, flat feel of the land right there at their steering-wheel elbows. What was it like to see the California High Sierra for the first time? What was it like to glimpse from five miles off those bone-white grain elevators standing up so spookily and beautifully on the Nebraska plain? I wish I knew. I never asked.

Once, in California, on a Sunday afternoon, they got to go to a studio-audience broadcast of Jack Benny’s coast-to-coast radio program. Once, in Times Square, at the Paramount, they got to see the Ink Spots in a live performance. The Paramount was a 3,664-seat palace at 43rd and Broadway. I remember my dad once telling me, sort of whistling it through his country-boy teeth, that he had never realized somebody could build a “picture show” that large. Decades after the war, when he was captaining big jets for his airline into and out of LaGuardia, he’d say: “New York? Shooee, Paul, that’s the jumping off place of the world.” He meant the grime. He meant the congestion. He meant the seeming ridiculous cost of everything. He meant what he regarded as the shocking incivility. Never mind that he himself had grown up in a deeply uncivil society of another kind, which is to say a segregated society, and that he held some of his ingrained bigotries nearly till his last breath, even as I witnessed him struggling against them. But, again, that is not the story I am telling here.

In Hartford, and with my mom two months pregnant, they found a two-dollar-a-week room in a boarding house with the toilet down the hall. “Your dad would be at work all day and I’d ride a bus downtown and look in the shop windows,” my mom once told me. “I had terrible morning sickness. We didn’t have any money. But I wanted to see what was in those windows.”

They knew, of course, what lay behind and under all of their adventuring: my father’s departure for the war. At nearly all of these assignments, he was training on new aircraft, building his hours and skills. It was the B-25 Mitchell bomber in La Junta, Colorado. It was the Douglas A-20 Havoc in Orlando. Toward the end, it was the P-61 at Hammer Field in Fresno, California, where the 549th NFS was formed and where I came along, on April 29, 1944. In the entire course of the war, only 706 Black Widows got built (as opposed to 9,816 B-25s), so getting into a P-61 squadron was kind of an elite aviator thing. He was so highly trained by the time he went over. I believe that all of that training helped save his life in more ways than one—it kept him stateside longer than for a lot of other flyers.

The P-61 Black Widow.

The P-61 Black Widow.

Bakersfield (where they’d been posted at least once before) was the last stop before the motor lodge goodbye. The late summer of 1944 must have been wrenching for them: they knew the leaving was near. In Amarillo that morning, they got up and got Marty and me dressed and got dressed themselves and ate breakfast and went outside and stood for some pictures. Later that morning, my dad and Charlie Kessler went out to the local Army airfield and hitched a ride on a government transport back to Bakersfield, to rejoin their unit. (Their squadron commander had given both lieutenants a small leave to accompany their wives as far as Texas.)

So the men flew westward that day. And the women drove eastward.

That same afternoon, back on the Coast, my dad logged an hour and 25 minutes of training in a P-61. It wasn’t his P-61, his Rita-B. Black Widow serial number 42-39516 hadn’t yet been assigned to First Lieutenant J.P. Hendrickson. (Best I’ve been able to trace, she was still coming off the assembly line at Northrup in Hawthorne, California.) The reason I know this arcane fact—that my dad logged some flying time at Bakersfield Army Air Field on the same day that he and my mom told each other goodbye in Texas—is because the record of it is in his military file. As I say, that file that got saved from the ’73 fire is gold. But it’s not the same as having my dad in front of me to ask what he might felt that afternoon, above Bakersfield, in his goggles and jumpsuit, practicing turns and rolls and dives and then shooting a few approaches, having departed his family only a few hours before, not knowing if he’d ever see them again. By then my mom and Edy and their unaware charges were probably somewhere up into Oklahoma, starting to think about that night’s pull-over.

I’d give a lot to know what my parents said to each other there at the Amarillo last. And I never got around to asking. Not in any specific way.

*

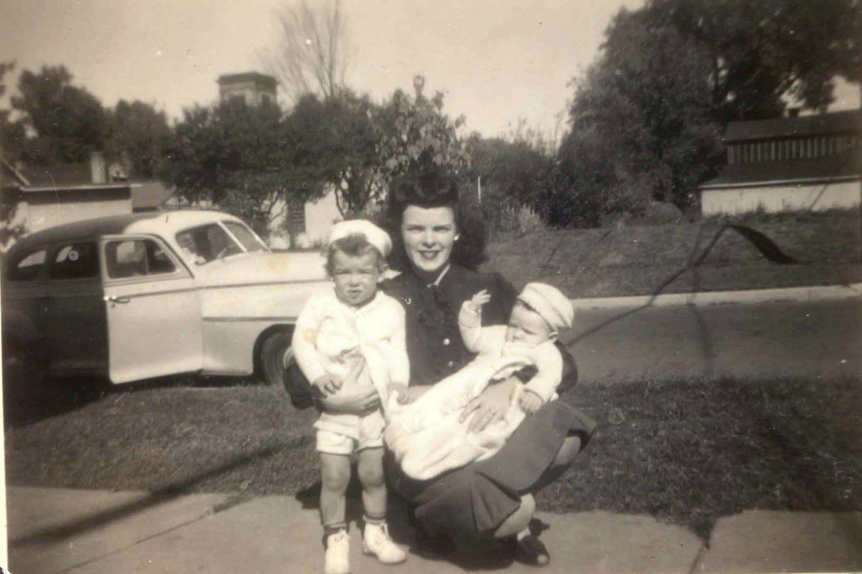

But I can report one small and fine and specific thing about the four-day Amarillo-to-Xenia run, which ended 76 years ago today, on September 23, 1944. Go back to my baby book and take a close look at the third image on the page. Do you see anything surprising? I had to look at it an awfully long time before an obvious question struck: how is that she looks so spiffy? Her hair is combed out, her collar snugged up tight. Marty and I are clean as a whistle. See the flung-open car door? I think these two war wives and the two cleaned-up babies have hit Xenia just seconds ago. They’ve hopped out—heck with the door. And Edy or maybe Nonna or Pop decides to document the arrival for the scrapbooks, for my baby book, on the sidewalk outside of 8 South Mechanic Street. Is it late afternoon? I think so. Nonna must have dinner on. Surely, they’ll all sleep fine tonight.

Photo via Paul Hendrickson

Photo via Paul Hendrickson

My mom died in Florida in 2015, at 92. My dad had died at almost 85 twelve years earlier. About a year before she died, I was sitting with her in her nursing home and talking about various things. I had my baby book. We studied the third picture on the page.

“But you look so spruced up, mom.”

She didn’t quite snicker in my face. “What, Paul, do you think I was going to go in on my parents looking like something the cat dragged in? Of course I was spruced up. I stopped at a gas station outside of town and took you and Marty and my suitcase into the women’s restroom. First, I got you two all scrubbed and dressed. And then I wriggled out of what I was wearing and put on nylons and a new dress I’d especially saved. I put on my makeup. Wouldn’t anybody have done that?”

Not so sure, mom, if you’re somehow reading this.

In any case, I keep staring, trying to dream myself in. In the present moment, when so much about the world seems uncertain and scary, some two-by-three snapshots of my parents pasted into a faded and broken-back book give me solace.

—————————————————

The preceding is from the Freeman’s channel at Literary Hub, which features excerpts from the print editions of Freeman’s, along with supplementary writing from contributors past, present and future. The latest issue of Freeman’s, a special edition gathered around the theme of power, featuring work by Margaret Atwood, Elif Shafak, Eula Biss, Aleksandar Hemon and Aminatta Forna, among others, is available now.

Paul Hendrickson

Paul Hendrickson, a former staff writer at The Washington Post, teaches nonfiction writing at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of seven books. His Sons of Mississippi won the 2003 National Books Critics Circle Award. He is working on a book about his father and World War II.