Small Data is the New Big Data

Two Designers Explain why Personal Documentary Trumps the Quantified Self

How many times did you apologize this week? How often did you have negative thoughts about yourself? What about directed to others? Which sounds did you hear in your surroundings? Chances are you’re probably not keeping track of the daily details of your life. You might not even be thinking of them as “data”—that’s for the cool, big “numbery” things like the heartbeats, daily steps or financial transactions your smartphone is tracking and giving you handy charts on.

Information designers Giorgia Lupi and Stefanie Posavec have just proven that if you want to get to know yourself or others better, “small data” is the way to go. “Data collected from life can be a snapshot of the world in the same way that a picture catches small moments in time,” they write in their new collaborative book, Dear Data, a collection of illustrated postcards representing their artistic, personal takes on seemingly mundane data collected over a year of their lives.

Lupi and Posavec live on both sides of the Atlantic (an Italian in New York, and an American in London); they met by chance at a conference in Minneapolis. “We already knew we shared a unique approach to data visualization—we draw; we start by sketching. The second time we met, we decided we wanted to collaborate,” says Lupi on a three-way phone call. They discovered they not only shared that but they were also only children, and the same age. That serendipitous moment led to them embarking on a project that would have each of them visually documenting one aspect of their lives a week, for 52 weeks.

Starting in the fall of 2014, each week, Lupi and Posavec chose a theme related to their thoughts, surroundings, behavior, or belongings. They collected data on that for seven days and, afterwards, came up with a way to represent that by drawing it in a postcard, which they would then send to the other. They started off with a week of clocks—illustrating how many times they looked at the time, why, and where—and continued with recordings of the times they said thank you, looked in the mirror, complained, had physical contact with someone else, or had negative thoughts. They always add personal context and observational details—regarding a week when they’re recorded their drinking, Posavec notes:

“I tracked whenever I had a drink. This proved difficult as the night went on (Note: I’m pretty sure I drank with dinner on Wednesday night (it was NYE after all!) but nothing was tracked . . . But I was drinking all day, so my memory is hazy.”

The results are a mesmerizing documentation of the beauty of daily life and of a forging friendship. Both are very gifted visual designers—see Posavec’s Writing Without Words or Lupi’s visualization of writers’ sleeping patterns for examples—and the postcards are beautiful in themselves, but it is their content that transcends.

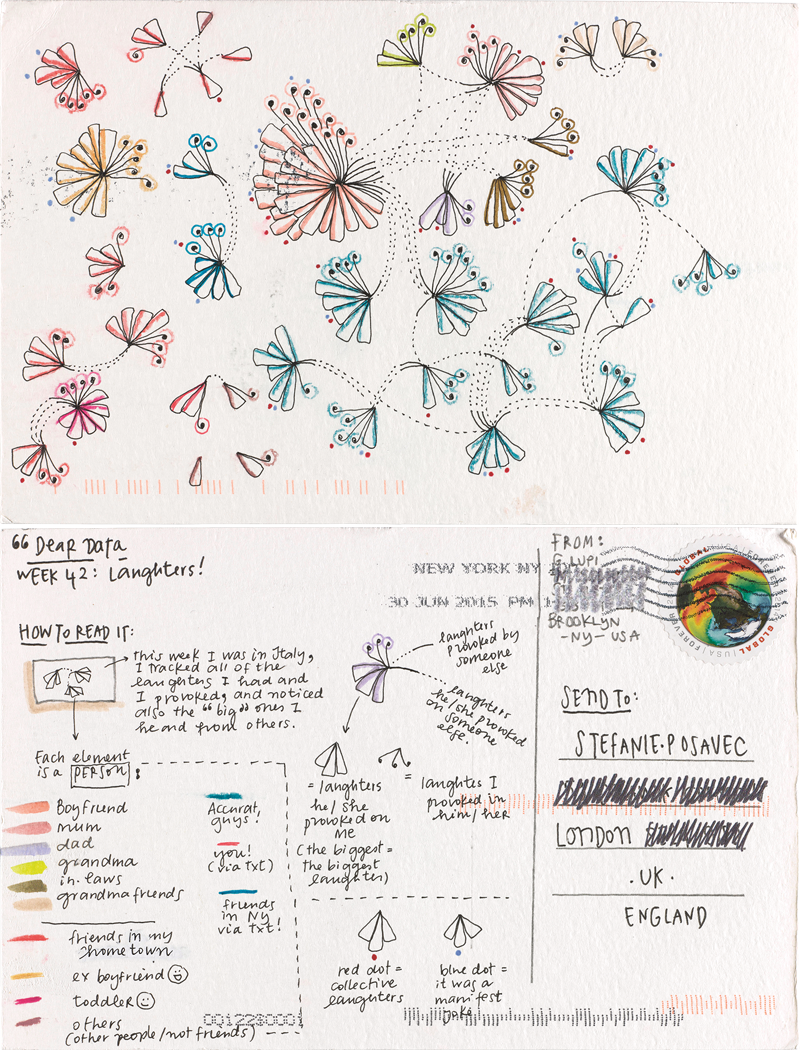

Stefanie Posavec on her favorite postcard from Giorgia Lupi: “I like her week 42, laughter, because in my mind, I like how she visualized her laughing data — it looks like laughter, it feels very evocative of nice laughter from me.”

Stefanie Posavec on her favorite postcard from Giorgia Lupi: “I like her week 42, laughter, because in my mind, I like how she visualized her laughing data — it looks like laughter, it feels very evocative of nice laughter from me.”

In the so-called age of “Big Data”, where we leave a data trail just by living (through our purchases, movements through the city, Internet browsing, etc), we’re surrounded by companies and governments that quantify us—and many eagerly use data-tracking apps to become more efficient human beings. Our data is aggregated, and algorithms are supposed to give us answers to anything—indeed, even to our love life. In this world, Dear Data is an invitation to step back, enjoy, and interpret the imperfect, subjective data of daily life. It’s a “personal documentary” rather than a “quantified self” project, its creators write.

Their slower, analog approach was, partly, a way to “push ourselves and see what was possible within our field, testing the edges,” says Posavec. They did try letting an app track them for the first two weeks but deemed it too impersonal. “Drawing helps us get closer to the data.” They write: “We shouldn’t expect any app to tell us something new about ourselves.”

In our conversation, Lupi reflects on data collection as a form of meditation: “We both agree that what we learned the most from a year of this kind of data collection is really to pay attention to what is on your mind, your behaviors and your surrounding. I now feel much more aware of what’s happening around me. It can be a form of meditation—or mindfulness, the simple act of actively noticing things—it makes you sensitive to the context. As you’re noticing things, it’s engaging. Whatever topic we would track, you needed to stop to acknowledge it, to write it down. It really changes your mind.

If their project was a “slow data transmission,” in Posavec’s words, this book equally demands a slow, calm read. Indeed, some of their detail-crammed legends take a few minutes to figure out. Over the weeks, the reader can appreciate their distinct drawing styles and personalities—and they can also see how Lupi and Posavec evolved from the “nervousness and trepidation” of the beginning to the more bold, colorful postcards towards the end.

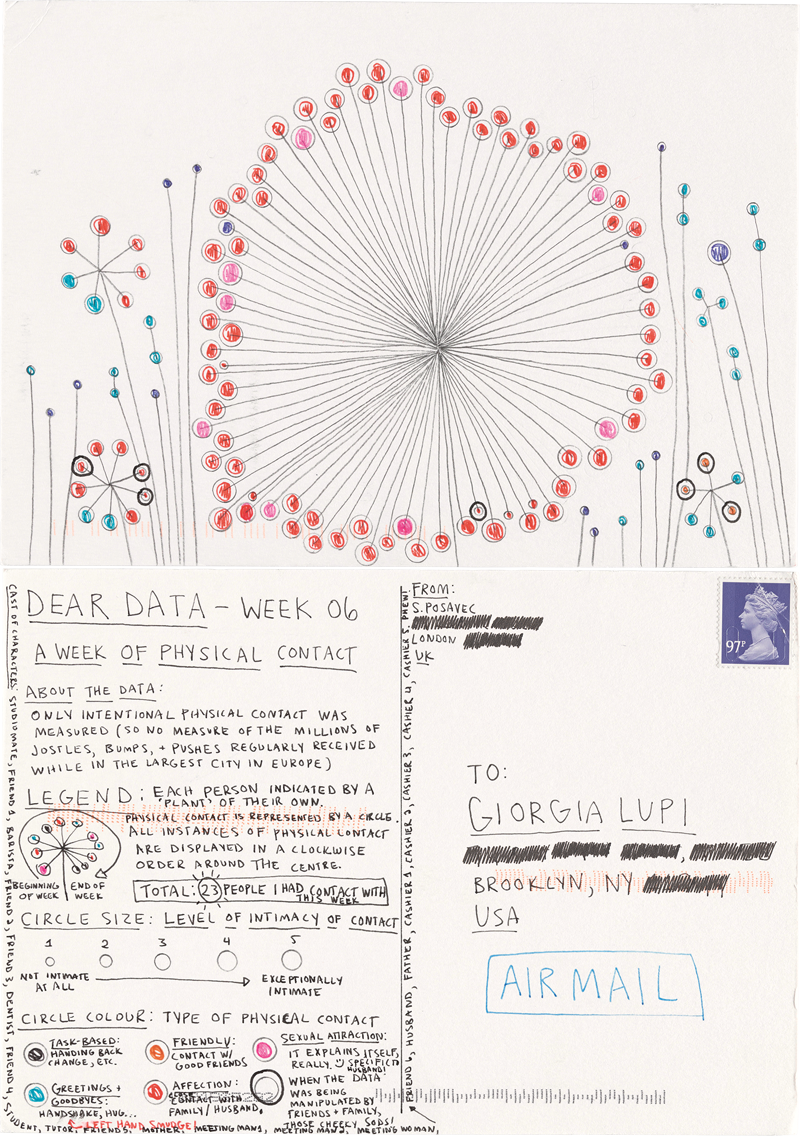

Giorgia Lupi on her favorite postcard from Stefanie Posavec: “I like her week 6, tracking physical contact. It’s so telling of her week, and the way she represented her husband jumps at you. Also because of the story of the week — we were both far away from our families, but that week Stefanie’s parents were visiting her — there was a memory of touching her parents for the last time for a while.”

Giorgia Lupi on her favorite postcard from Stefanie Posavec: “I like her week 6, tracking physical contact. It’s so telling of her week, and the way she represented her husband jumps at you. Also because of the story of the week — we were both far away from our families, but that week Stefanie’s parents were visiting her — there was a memory of touching her parents for the last time for a while.”

The two designers have forged a visible friendship through this project alone. Posavec says: “Using data-gathering forced us to really be honest with each other about small details of our lives. If you work with data, the datasets need to have a certain level of integrity. This forces you to be more honest than you might be in conversation with your friends at a bar. We definitely know each other a lot better. What I think is interesting is that, in our real life interactions, we know what each other will be like in real life because we’ve discovered that through the postcards.” Lupi adds: “When you write your stories with data, it’s more intimate—your language is limiting, you get to the core of what you want to say. We didn’t speak Italian or English, we spoke data.”

It wasn’t always easy. Some of the postcards got lost in the mail: “Giorgia had a mailbox. I had a mail slot. My postman was terrible—he would fold them into four, and sometimes leave them outside in the rain. It really made me angry with him!” says Posavec. And their friends and partners would occasionally try to interfere: making silly noises on the week they were recording sounds, or touching them repeatedly they were recording physical contact. “At the end of the week I was trying to avoid contact!” laughs Lupi. “Our friends and the people around us were into it,” they say, and that is beautifully reflected in the book as well.

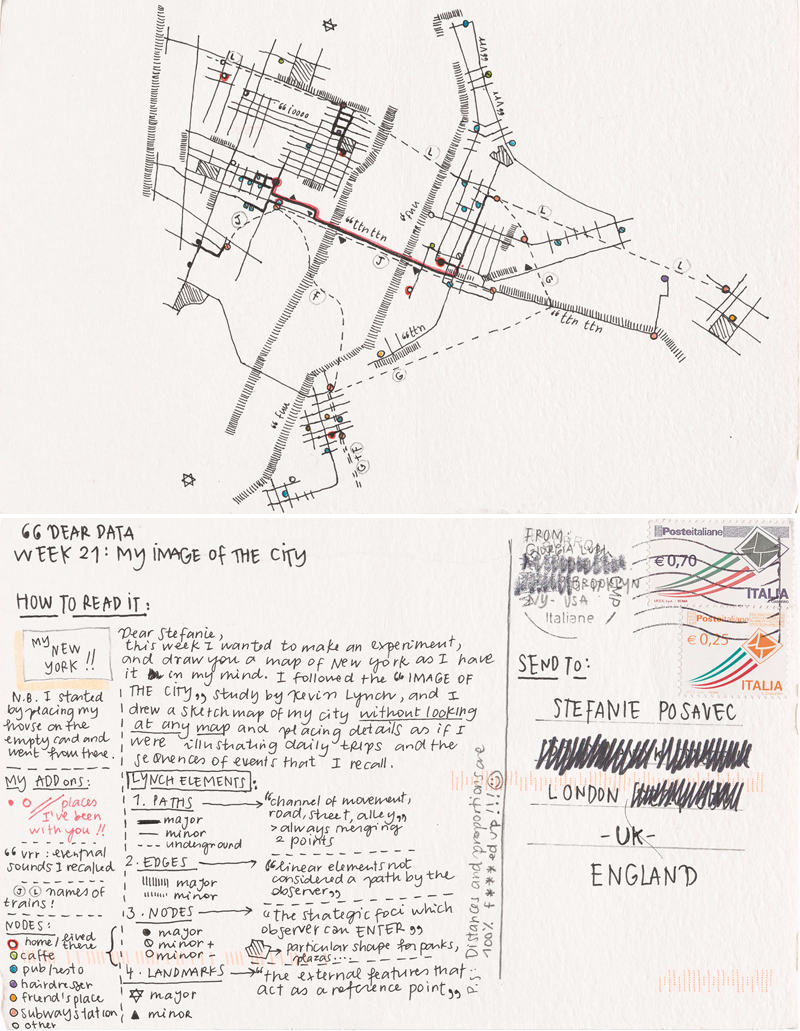

After realizing that, no matter how meticulous they were, the data-collection was affecting their behaviors, they would be honest about it in the postcards, they introduced “performative weeks”—forcing themselves to smile to strangers for a week, for instance (something that turned shyer Posavec into a “sulky, petulant teenager being forced to do something she doesn’t want to do,” and she went on strike at the end of that week “in protest to assholes!”), or drawing mental images of their cities or their past relationships.

Giorgia Lupi’s New York, from Dear Data

Giorgia Lupi’s New York, from Dear Data

Both seem to have been born for this. While Posavec remembers feeling excited, as a kid, at being able to capture a moment in time when she helped her father fill out baseball scorecards, Lupi recalls how she took pleasure in categorizing all kinds of items into folders and tagging them with maniacal care.

Lupi and Posavec hope this book inspires others to do the same—an idea that might seem ludicrous when taking a glance at their drawings. Don’t let the fear of the blank page paralyze you, though, says Lupi: “I always think how popular these coloring books are . . . Everyone wants to be creative, but starting from scratch is scary. Drawing your data is the same, it’s also a template—a spreadsheet can be your starting point. Data visualization is not matter of tools or programming languages—it’s matter of starting to see data everywhere around you. In every word you say.” As Lupi says, small data is the new big data.

Marta Bausells

Marta Bausells is an editor-at-large for Literary Hub. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Electric Literature, Literary Review and other publications, and she is the creator and former editor of the Guardian Books Network. She lives in London and originally hails from Barcelona. You can find her on Twitter @martabausells.