Reflections of

the bones, sole

images sans

images

of the gestations and agonies.

Touch,

folio III

The old man ran. He quickly lost his hat, his staff. He ran. Ran without haste. A steady pace that took him surefooted through the back-of-beyond zayonn undergrowth. He sent his body across dead stumps, laid low the kneeling branches with his heels, hurtled down reclusive ravines devoted to pure silences. Around him, everything shivered shapeless, vulva dark, carnal opacity, odors of weary eternity and famished life. The forest interior was still in the grip of a millenary night. Like a cocoon of aspirating spittle. Another world. Another reality. The old man could have run with his eyes closed: nothing could orient him. Sometimes he bumped into unseen little branches, his toes, ankles, face—whipped! He had to run behind his bent forearm to protect his open gaze. Then, as he went on, the trees drew closer together in the thickest of pacts. The boughs fastened themselves to the roots. The raziés-underbrush gave lavishly of its irritating prickles. The Great Woods loomed. His pace slowed. At times he had to crawl. The enveloping vegetation stuck to him, sucking, elastic. With bleeding elbows, step by step, he made his way. It went up. It went down. It monta-descendre : up-and-downed. Sometimes, the ground disappeared. He tumbled then into sheets of cold water that gurgled with emotion.

The old man felt close to the sky. The stars diffused a blissful radiance etching the forms of the ferns. But the darkness—so intense—sent that pallor to him in a starry dust: it dissolved all forms. Often he headed down again, he had the impression of descending endlessly, of reaching even the fondoc-fundament of the earth. There he thought to find the vomiting of lava or the fires said to flame from the foufoune-pudenda of femmes-zombis. The torn rachées of his heart throbbed within him, stirring liquid, glowing embers that shattered his body to rejoin the sky. Such incandescence summoned up wild earthy fumes in his bones. Leaves, roots, trunks, took on the odor of ashes graced with those of green corn and newborn buds. Water, invisible, showered in drops from certain large leaves; at other times, it became a sweat that greased his skin until he seemed covered with scales. Unsettled by an incontrollable energy, he was neither hot nor cold. He did not feel the raide licking of water or those thorns prying at his fingernails, or even those sharp branches that in trying to disembowel him made a lovely mess of his livery.

Nothing seemed able to extinguish his energy. He proceeded like a ship at the mercy of a liquid womb. From going up and then down, and feeling up high after coming down, he no longer even knew where the sky was, where the earth lay palpitating, which side was his left, where to go to the right. This was no longer the earlier absence of landmarks but a profound disorientation. He advanced with the impression of standing still. At times he felt he was backtracking even while convinced he was heading for the heart of the Great Woods.

“Soon, he was not conscious of anything. His body no longer perceived itself.”

In the beginning, he had been scared shitless. He expected to suddenly see the monsters feared by the folktales: the impish Ti-sapoti, the dog-head women, the fireball soucougnans, the flayed-flying-women perfumed with phosphorus, the unbaptized misery of coquemares, and the persecuted zombie persecutors. But he saw nothing of all that. He saw nothing at all. Except this tragic blackness. This slapping, lashing vegetation. This energy living inside him as a stranger. The more he imagined the monsters, the bigger his eyes grew, the wider his mind opened, and the more the darkness maneuvered around him. His skin grew sensitive to the acrid breath of winds bruised beneath the leaves, to the velvety touch of the dewdrops that clung to him, delighted to be visited after century-times of solitude. His skin became porous, then it became powdery, then it must have gone away because he thought he came apart in an effervescence amid which only his bones supported him. In time, the Great Woods wrapped-him-up-tight. Forced him to be still. Stillness was, there, a plunge into the abyss and an elevation. It taught him the nausea of mummies and of people who are brought back to life, the confused panic of those walled up alive, and the exquisite bitterness of the martyr’s coma. Abruptly, this hold on him let go as if at the entrance to a cradling clearing. Then he ran with all his might, jumping at random over imaginary tree trunks, swerving aside at random, lying down at random, leaping at random, advancing according to the laws of a dance that allowed him, all unknowing, to avoid a thousand obstacles before a green hand grabbed him once again. It took him a while to realize this: a magnetic prescience let him be a bole, a moss, a branch, a spring, a tree. He flowed within their traceries. He no longer felt their shocks, or else passed through them like a cloud of pollen. He felt as if he were a shadow, then a breath, then a fire, then opaque flesh that restored to him—brutal—the world’s horde of sensations.

Soon, he was not conscious of anything. His body no longer perceived itself. Persevering in his flight, he pinched his limbs, touched a wound, brought a lick of fresh blood to his lips and was reassured to find it tasty. That was not enough to put him back together. He experienced the distress of ruins that had once been sumptuous cathedrals. The Master claimed that the runaways he had not managed to catch had dissolved into the Great Woods. This fugitive felt he had become water within the water of the patient leaves. He had no fear whatsoever, pièce pensée—not a jot of thought: nothing, save the motionless onrush of that dark mass that lived inside him and surrounded him. So then he strove to go faster, jump high, run raide, fly far, meld all this together through speed. It seemed to have no effect. He thought he was dying, losing his struggle against life’s miseries, and expected to emerge from the cold glue of a nightmare, but patting his face gave that the lie: he was indeed bien éveillé, bien réveillé—wide awake, well awakened. Then he muttered the word éveil, éveil léveil: awakening, awakening th’awakening, opening his eyes wide without fear of seeing them burst by a branch. Éveil léveil. He saw nothing. Felt nothing. Only this motionless aspirating movement. Éveil léveil he feared he was dead, buried by mistake in a nail barrel, and some old reflexes returned. He was forced to listen to himself in unknown zones, to isolate the sound of his heart, more powerful than ever. He perceived the giddy whirl of his blood that he had slowed down all his life. He experienced, as if torn, the sensation of every bit of his body, every unknown organ, every forgotten function. He apprehended the circulating sun that united and drove them. His run had propelled his flesh to its ultimate limit and his formerly separate organs, reacting en masse, passing beyond all distress, kept on going, leaving him panting with innocence in a hazy awareness of himself he had never known before.

Plenitude. His perception encompassed the darkness around him. He recovered the feeling of displacing himself, changing position; he avoided the trees with calm authority, and moved through the undergrowth with ease and a fine air about him. He chose no direction, sought nothing in the hopeless darkness. Fearing a return to his starting point, he conjured up for himself an awl of light emerging inside him and toward which he swiftly donna-descendre, began to descend. This fixed point gave him the illusion of orientation and its immediately beneficial reassurance.

He apprehended his aroundings differently. The desolate darkness revealed to him the texture of humus, the tangled ages, the regal waters, the pensive strength of tree trunks, the verve of the sap hidden in this vegetation. All this was enhanced by a profusion reflecting great energy. This élan sustained him from that moment on.

Suddenly, the light was different. Painful. Daybreak had arrived. Gluey luminescence came down the tall trees. A foggy dawn suffused their trunks and drowned the underwood with milty mist. He saw a tortuous—bloodied—vision—but shut his eyes and ran more vigorously, overcoming obstacles like a rush of water. No time to drink from the springs, where his heels sank in deep. He had no desire to drink there: water seemed to impregnate him. Immanent, it slaked his thirst from within. Now and then he half opened his eyes and found himself lashed by ever-more intense light. His eyelids burned him; he kept them shut tight. He thus avoided discovering those great unknown trees in any way other than through the obscure alliance now familiar from those initial hours. He tore off a strip of his livery to make a blindfold. His race toward the luminous point spiraling within him continued like that. Inside. All out.

The point vanished when he heard a brutal growling pitched high.

Far away.

Not a yowling, but a jaggedy howl.

The mastiff was hunting him.

Fini bat . . . Battle’s over! he thought.

He sped up but was dismayed at losing his point of light. So, then, he bent his spirit toward the earth. He listened, all ears, to the pretend silence of the soil, teeming with hay mushrooms, the burrowing of roots, the dense panting uh-huhs of boulders, the limpid light of scattered streams like copperbright sighs. He listened some more, desperate, then finally heard. Thumps. Muffled thumps. Bitunk. Bitunk. Bitunk. The pounding of the monster’s paws pursuing him. They almost matched the rhythm of his heart. Then he accelerated to make those rhythms one, so that he might use this sound sent to run him down as a guide for keeping his distance. Fini bat . . . , he thought again, mulling things over.

__________________________________

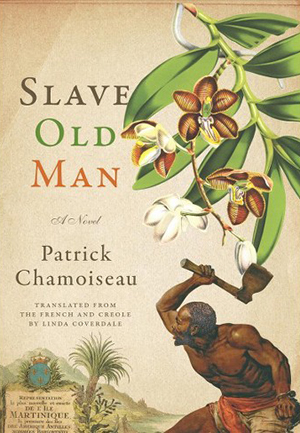

From Slave Old Man. Used with permission of The New Press. Copyright © 2018 by Patrick Chamoiseau.