Sixteen in Queens and in Love With Lord Alfred Douglas

Dylan Byron on the Self-Discovery of Early Literary Love

When I was a teenager, Oscar Wilde brought me back in queer time. I borrowed his barely canonical books and found a politics of dandyish self-making that had nothing to do with the gyms, pre-code Hollywood divas, or subway urinals my few gay friends told me about. I removed myself from millennial New York. I created a closet like no other.

It was easy to imagine myself as Oscar Wilde because I lived in a crumbling outer-borough house and my parents were artists and he was from Ireland and his mother Speranza was a poet who collected folk tales. The awkwardness of these facts, together with my large head, English names, darkening hair, and bookishly pale skin implied to my adolescent mind a certain correspondence. Also, even though I was only 16 years old and he had been born to the 9th Marquess of Queensberry 133 years ago, I was in love with Wilde’s boyfriend Lord Alfred Douglas.

Scanning books of homoerotic photography like some analog Grindr, I combed the queer canon for plausible images of literary homosexuals. I wanted to know what everyone looked like. I couldn’t see myself dancing into adulthood at Splash Bar; I needed a different model. With a superficiality of which Wilde might have approved, I picked him for his cute boyfriend.

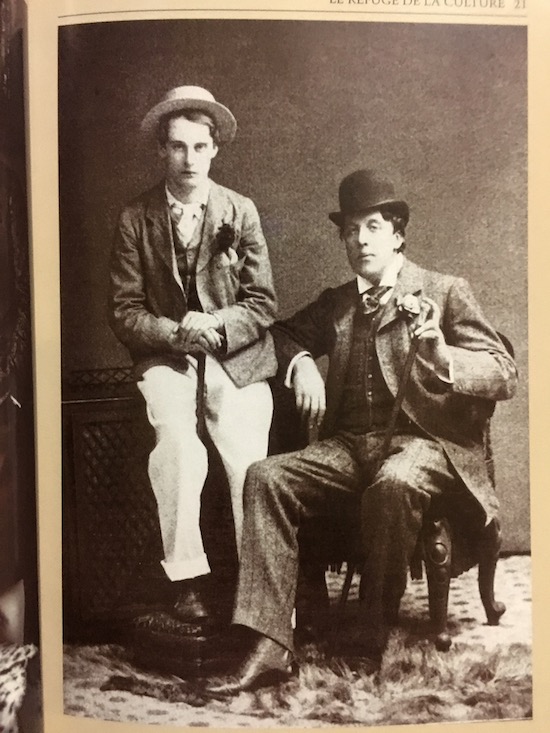

In a photograph reprinted in the 680-page biography of Oscar Wilde I pulled out of a pile at the Strand that year, Douglas looks exceptionally slight, sitting awkwardly with thin, unsmiling lips, high, fine cheekbones, narrow eyes, rounded shoulders and greasy, close-cropped hair parted to the left on a diagonal with four strands streaking his brow: exactly my type at the time. By 2003 I was firmly convinced that “Bosie” Douglas was just as delightfully “boysie” as his mother’s nickname suggested. Though my school was in Manhattan, I had read extensively in the literature of English public schools: Waugh, Rupert Brooke, John Addington Symonds, endless books of letters and minor biographies. I rented Merchant Ivory films. I pictured mutual masturbation. I knew all about fagging. I learned the codes.

Since my Ichideal and super-crush were both from the 19th century, my ties to the 21st became somewhat attenuated.If photographs of Lord Alfred Douglas from the 1890s were my Rock Hudson pinups, Oscar Wilde was my Liza Minelli. Instead of belting out songs from Cabaret in my bedroom, I learned ancient Greek and steeped myself in the iconography of the aesthetic movement. As an undergraduate Wilde wore a cello coat; as a high school sophomore I swept along in floor-length camel. He favored the sunflower and the lily; I chose the hyacinth. Given that for his viva Wilde could translate the most recalcitrant passages of the New Testament by sight, sailing right through their tortured syntax and watery vocabulary, why shouldn’t I? I stayed up late reading Pindar and Homer. I took a disintegrating copy of Theocritus from the darkened basement of the school library. I scoured the Greek Anthology for ideas. I took pleasure in speech and language. Prescinding questions I practiced giving answers.

Since my Ichideal and super-crush were both from the 19th century, my ties to the 21st became somewhat attenuated. My mother realized I was gay by discovering a florid essay on a male friend’s beauty written in the style of Walter Pater on my desk. A Swedish classmate found himself the bewildered recipient of dactylic hexameters. For English 10-8, I handed in poems that were somewhere between the post-Victorian and the poststructuralist (I knew some French and had tried to read Barthes and Derrida). One poem contained the couplet: “The physical confirmation of signs, rests cupped / in my palm, sweet remembrance sticks to my fingers.” Over the phrase, “restraint I shall not brook,” the teacher wrote “no kidding!” At the top of the page, he (for of course it was a he) added: “umm…my goodness! A bit, shall we say, overblown?” Though still a boy myself, I had no doubt that I was too old to be loved by other boys for anything but style and language. It was a protective, oddly winning move; you can’t really lose if you decline to play the game.

By June, the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down state anti-sodomy laws in Lawrence v. Texas, but the trials on my mind were Wilde’s, especially the second one in which he made his famous speech explicating “the love that dare not speak its name” from Douglas’ poem. Sitting up at night I loved to quote the classicizing peroration about Plato and Michelangelo’s sonnets to myself. In fact I became so absorbed in the rhetorical drama of Wilde’s martyrdom that I grew insensitive to the larger point that his conviction for gross indecency, together with the Eulenburg affair in Germany, would haunt virtually every proximate figure in the library of homosexuality I went on to construct: James, Firbank, Gide, Proust. The most public articulation of turn-of-the-century homosexuality was also the most public case of its punishment.

In the years that followed, Wilde came to seem more like a liability than a hero, the carrier of a suspect flamboyance that even the fact of his demise couldn’t decontaminate. Out of the closet generally since my mid-teens, I went from openly homosexual to openly discreet. I swapped chalk-stripes for t-shirts. I wore jeans. I got crew cuts. Matriculating in the Sheldonian myself at 19, I couldn’t have told you which college was Wilde’s. (It was Magdalen.) Whenever an English hookup and former Vivienne Westwood model suggested I part my hair down the middle like Oscar, I concluded he was taking a new drug. When a German friend asked me what I thought of Wilde’s plays, I was actually offended. I told him I preferred Hegel.

Well into my twenties, I was still embarrassed for my sad adolescent self—patchily armored in passé tweeds on the uptown 6 train, pathetically clutching an Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray, flashing its cover to all and sundry in some desperate maneuver of affirmation. I knew all the Greek particles but no one had told me about Julia Kristeva’s essay on abjection.

By the time I remembered Oscar, I was already in love with Oleg. At the end of our first date I was re-reading Dorian. When he came back from Berlin we swapped sartorial pasts. He always came in Gaultier Femme. I found my old suits. We spent our first fall together with Benjamin and Baudelaire, Barbey and the Beau Brummell. We loved Dick Hebdige on dandy punk, Didier Eribon on insult. Wilde was everywhere but nowhere, a ghost and early sanction. Thus Sundays we stalked Manets in the Met in sailor stripes, later the Staatsoper in tails and a monocle. One page a night we read Thomas Bernhard; each compound noun gets a kiss. We tell stories. We forget men. Together, we give ourselves permission.