Six "reboot" novels to put on your radar.

A handful of books that bounce off the canon.

In a recent review for The Baffler, Adrian Nathan West considered a pair of novels written as responses to existing classics. This got me thinking about literary reboots.

There are lots of novels adapted from myths (Madeline Miller’s Song of Achilles, Chigozie Obioma’s An Orchestra of Minorities). The fairy tale has fans (Julia Phillips’ Bear). Even the Bible has borne adaptation, in novels by Maryse Condé and Colm Toibin. But what exactly draws an author back to the recent canon?

At a glance, many response novels are interested in the revisionist or reparative read. In a sharp piece for Lux, Natalie Adler recently considered a spate of “queer and trans novels that complicate the Lolita plot.” Books like Geraldine Brooks’ March or Sandra Newman’s Julia re-tell a story from the vantage of an NPC. Such books offer fun lessons in craft possibilities. What changes in a story when the POV does? And, can you fill a hole even as you pay homage?

In case you also feel like riding the train backward into the stacks, here are a few book “remakes” for your radar.

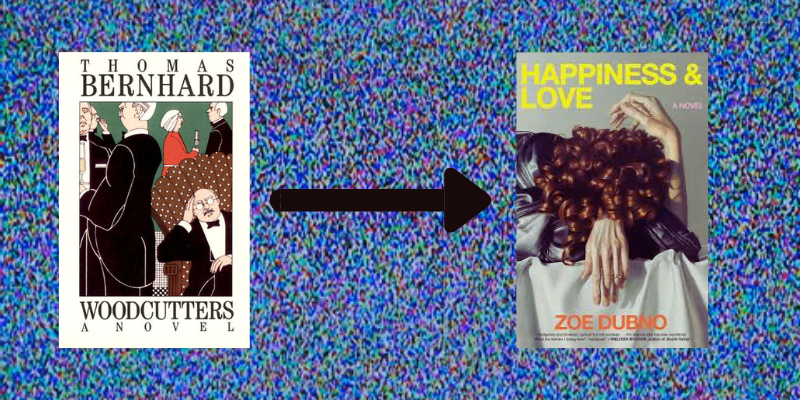

Zoe Dubno’s Happiness and Love nods to Thomas Bernhard’s Woodcutters.

As West reports, Dubno’s update puts us in the head of an unnamed twentysomething who judges her peers at a cocktail party. This frame borrows from Bernhard’s tailspin of a novel, set entirely in a narcissist’s armchair.

The adaptation here is quite direct, plot-wise. As West notes, “Vienna is transposed into Manhattan, the Graben into the Bowery, Eugene and Nicole are the Auersbergers, Rebecca is the ‘movement artist’ Joana, and the actress is the actor from the Burgtheater returning from a performance of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck.”

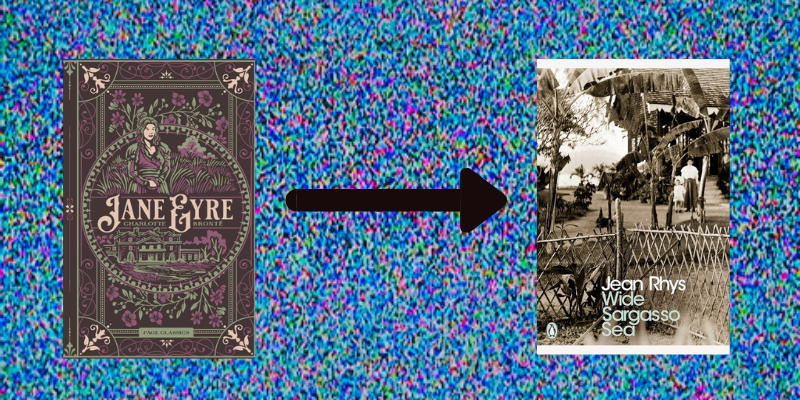

Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea is a postcolonial response to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

Rhys’ 1966 novel concerns Mr. Rochester’s first wife, the notorious Madwoman in the Attic. Rather than that scrappy little orphan, this “landmark of feminist and postcolonial fiction” centers Antoinette, a Creole woman whose “madness” is situated in the context of a racist, patriarchal society.

When asked about her motivations for writing the book, Rhys said, “she seemed such a poor ghost, I thought I’d like to write her a life.”

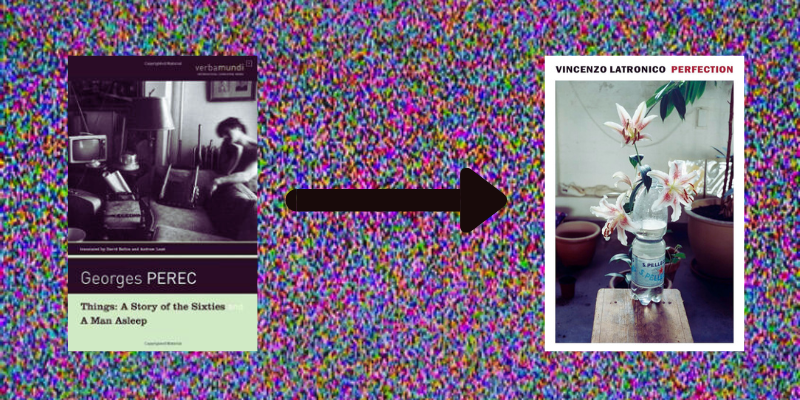

Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection is inspired by Georges Perec’s Things.

West observed that Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection “draws on” Georges Perec’s Things. And the former, a close look at a drifty PMC couple trying to live their values and enjoy their privilege, “is not so much a remake as one of those sequels released decades later, situating the same protagonists in a changed world.”

Like Perec’s, Latronico’s novel is interested in categorizing a consumerist milieu. Both novels take on the spiritual hollowness that can accompany a life built on material aspirations.

Zadie Smith’s On Beauty nods to E.M. Forster’s Howard’s End.

Smith’s “sly and inventive recasting of E.M. Forster’s masterpiece” is one of those vibier response books. Certain plot furniture has been airlifted into a present day context, while some has been left behind. In Forster’s Howard’s End, a legacy dispute draws two families together around an estate. On Beauty, on the other hand, brings its players together on a college campus.

Bohemianism in the first text is made into multiculturalism in the second. And though Smith makes open reference to the language in Forster’s classic, she also invents a plenty.

Percival Everett’s Pulitzer prizewinner James is a response to Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Everett’s much-feted novel is, as you may have heard, a revisionist response to Huck Finn. But in the update, we find Jim in the driver’s seat and Huck mostly offstage. This is a classic revisioniste= reading, centering the character who was denied agency and voice in the original.

But as Everett told the Booker Prize, the intention here isn’t to punish. “I hope that I have written the novel that Twain did not and also could not have written. I do not view the work as a corrective, but rather I see myself in conversation with Twain.”

Cervantes’ Don Quixote got the modern treatment in Salman Rushdie’s Quichotte.

Rushdie’s spin on the epic is most interested in borrowing Cervantes’ structure and form. As Johanna Thomas-Corr wrote in The Guardian, in Quichotte “We’re not in La Mancha any more but Trumpland. Our knight errant is a dapper old duffer named Ismail Smile who loses his job as a pharmaceutical salesman and sets off across America with a teenage son he has dreamed up named Sancho.”

This remake is most curious for the contrast—Cervantes’ novel is thought to be the first realist piece of literature, where Rushdie’s update is decidedly absurd. But the times, they are a changing. Maybe every generation of readers get the spins they deserve.

Image via

Brittany Allen

Brittany K. Allen is a writer and actor living in Brooklyn.