Silence is Power: Sara Nović on Joanne Greenberg’s In This Sign

“The quietness... forces readers to reckon with the intricacies of deaf people as people.”

When it comes to deaf culture, I can be protective. The American deaf community is a diverse and vibrant subculture, with our own rich history, language, and shared values. We are also small, tight-knit, and extremely marginalized by the larger hearing society around us, which can make us proprietary about our stories.

At the heart of deaf culture is American Sign Language (ASL), a language different from English not only in its modality, but also in its vocabulary, grammar, syntax, and higher-level linguistic concepts. In part because of this language barrier, most hearing people can’t or won’t broach the divide between our worlds in a meaningful way in their lifetimes. As a result, deaf characters in fiction are a rarity, and when they do appear they are often poorly rendered. Typically, deaf people in literature and film are pitiable, isolated, and innocent to the point of infantilization. These failures of the hearing imagination—the inability to comprehend that deaf people experience the full range of human emotions, have rich inner lives, and can be successful—are common on and off the page.

Greenberg is a writer who is clearly unafraid to approach complex topics from perspectives wholly her own, uninfluenced by trends of the zeitgeist.

Because of all this, we can be dismissive of hearing-made art about deaf culture. Theoretically this isn’t the best strategy, but then again, we’ve rarely been wrong. Across centuries of American literature, writers again and again confuse the physiological fact of deafness with the state of our intellect or our capacity for feeling. But being a nonspeaking deaf person or one with heavily accented speech does not indicate that we are empty vessels in which to dump stereotypes, or to use as symbols. We have much to say to those who will take the time to listen.

Enter Joanne Greenberg. Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1932, she is best known for her second novel, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden. Published in 1964, it is a semiautobiographical account of a young woman’s inpatient stay at a hospital while being treated for schizophrenia. Greenberg’s portrayal of mental illness is decidedly unbeautiful, a departure from other cultural forces at the time, notably Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar published one year earlier. This was an explicit motivation according to Greenberg, who said in an interview with the National Association for Rights Protection and Advocacy (NARPA):

I wrote [I Never Promised You a Rose Garden] as a way of describing mental illness without the romanticization that it underwent in the sixties and seventies….During those days, people often confused creativity with insanity. There is no creativity in madness; madness is the opposite of creativity, although people may be creative in spite of being mentally ill.

Greenberg is a writer who is clearly unafraid to approach complex topics from perspectives wholly her own, uninfluenced by trends of the zeitgeist. I can imagine that her lived experiences with mental illness have also made her familiar with the feeling of otherness in a society that so values “normalcy.” It makes sense, then, that Greenberg’s interest was piqued by the deaf community, for whom her husband was working as a vocational rehabilitation counselor in the 1960s. In learning more about his clients and the systemic barriers they faced, Greenberg studied ASL and has since worked to establish deaf-accessible mental health programs at hospitals nationwide.

Even knowing this, when I first cracked In This Sign, I was nervous about how an older book might portray deafness. Quickly, though, my worries were allayed—from its first pages, it’s clear how effective Greenberg is at capturing the nuances of deaf culture.

Originally published in 1970, the novel details the lives of deaf couple Abel and Janice Ryder, from their school days up through their eldest grandchild’s college years, a timeline that spans from the 1920s to the 1960s. Abel’s rural upbringing and attempted mainstream education result in language deprivation—an isolating syndrome that not only affects one’s ability to communicate, but also eventually causes cognitive damage. Most of Abel’s childhood confusion and fear are crystallized in an upsetting sequence in which his mother shouts “oo” at him repeatedly, then sends him into town alone, where he sits in a strange room all day. He does not realize until decades later, after learning ASL and having children of his own, that she must have been saying “school.”

At the time of In This Sign’s publication, ASL had been recognized as a language for only about a decade; it was previously understood as “gestures,” or a bastardized version of English on the hands. As a result, American deaf education was only just beginning to wriggle out of the ironclad grip of the oralist ideology that had near unanimous rule since the late nineteenth century. “Pure oralists” believed that deaf people must be taught to speak and lipread, and that sign language should be eradicated. Children caught “waving hands” were punished—their hands tied to desks, slammed in drawers, and struck with rulers.

Eventually, Abel is freed from the confines of his isolation when he is sent to a school for the deaf as a teenager and begins to learn sign language. The school itself, though, is oral, as would have been typical of the 1920s, meaning the site of most deaf students’ education was not inside the classroom at all:

Every day for two hours, candles were blown out to make the letter P and mouths moved to letters and pictures on the blackboard and the students stared at tongues and teeth and lips—dill, till, still, skill—but the words, the real words were behind the outhouse, waiting; the Language given and taken quickly at the fence; the forbidden Signs made their users rich.

Oralist programming prevented a lot of deaf children from reaching their academic potential; however, the gathering of deaf people together in campus spaces allowed the children themselves to pull one another up out of language deprivation to a degree:

[Abel] began, very slowly, to wonder about words and thoughts themselves. Perhaps there were words for things not seen or touched….The more words Abel learned, the more things had meaning; the more meaning, the more memory.

Simultaneously, Abel’s new love for language bleeds into his admiration for a fellow student, Janice. Because Janice grew up boarding at the deaf school, she has always had sign, which is the thing that draws him to her:

How busy she was, and how wise, with plans and ideas, with friends, angers and the small wars of enemies. To Abel, hand-mute in the mind-silence of his farm and Hearing school, these plans and arguments were so wide a life, that they seemed magic.

Meanwhile, Janice, who is more educated than Abel but has rarely left the confines of the school, is enamored of the possibility of “Outside” that he represents:

Janice loved the idea of traveling; she loved all motion, all change, and Abel, who had spent his life in The World, who must have traveled easily from farm to town to city, seemed to her and the others a prince of promise.

Like many young people, Janice and Abel are in love with the idea of each other and of the gaps in their own lives the other might fill. They quickly bond and plan to build a life together. While Abel delights in his new ability to make sense of the world around him through language, ultimately the school has left both him and Janice ill-prepared to navigate a hearing world designed to hide and, eventually, eradicate them.

The idea behind the pure oralist movement—emphasis on pure—wasn’t so much effective pedagogy as xenophobia. Its rise at the turn of the twentieth century coincided with the burgeoning popularity of nativist and eugenics groups, which were concerned with how to forcibly assimilate the large number of immigrants arriving on America’s shores, as well as the language and culture of deaf people, who seemed to them just as alien as foreigners. Deaf and disabled people who found themselves in federal custody were often subject to compulsory sterilization. As for the broader civilian populations of immigrants and deaf people alike, another solution was posited: Just speak English.

Around this time, Scottish immigrant Alexander Graham Bell used his budding fame as an inventor to become an influential spokesperson for both nativism and eugenics. In one 1913 letter to a friend, he wrote, “I believe that, in an English speaking [sic] country like the United States, the English language, and the English language alone, should be used as the means of communication and instruction.”

Having come from a family of speech teachers, Bell was quickly considered an authority on oral education. Perhaps his most infamous statements on the subject came from an 1883 address to the National Academy of Sciences titled “Memoir Upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race”:

Those who believe as I do, that the production of a defective race of human beings would be a great calamity to the world, will examine carefully the causes that will lead to the intermarriage of the deaf with the object of applying a remedy.

Bell never outright advocated for the sterilization of deaf people. Instead, his “remedy” was a cultural one: the eradication of sign language. Without sign, deaf people wouldn’t be able to congregate with ease and would thus be forced to assimilate. The thinking was that fewer deaf couples would mean fewer deaf babies, although the recessive nature of most genetic deafness meant this was mostly false. The very real result was a dark age for deaf children: Deaf teachers, who could not teach speech, were squeezed out of teaching roles, leaving deaf children language-deprived and uneducated.

Greenberg’s novel is nuanced in its portrayal of deaf people compared to the general understanding at the time, appearing as it did after nearly a century of pure oralism’s rule. Impressively, Greenberg is also leagues ahead of her contemporaries; deaf characters of note immediately before and after the publication of In This Sign are almost laughably one-dimensional in comparison to Abel and Janice, with even talented writers seeming either incurious about dismantling deaf-related clichés or bolstered by the rhetoric of saviorism to speak over the deaf in problematic ways.

Carson McCullers’s John Singer, in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, is saintly, a receptacle for hearing people’s secrets and feelings, and once he is full to the brim, he is disposed of; Singer’s deaf friend, Spiros, is also dead by novel’s end. Eight years after In This Sign, Stephen King’s The Stand, with its “deaf-mute drifter,” Nick Andros, presents a cornucopia of problems, from the writer’s questionable comprehension of the physiological components of deafness and speech, to Andros’s sacrificial death for the lives of his hearing companions, to his reappearance in dreams, where he can always speak and hear. (In whose dreams, exactly?)

By contrast, Janice and Abel find agency in using the stereotypes others believe about them to get what they want. Of their finding ways to be together on campus, Greenberg writes:

Most of all, they used their deafness. They were all and completely mute; they understood nothing, they agreed to everything. They nodded and smiled and said yes to everyone….[T]hey promised to reform and then went where they wished.

Later in the novel, Abel uses his landlord’s assumptions of his diminished intellectual capacity to procure another week’s stay in their apartment as they look for a new place to live. In their silence, the couple finds power.

Greenberg, too, seems to make use of this—there is power in the novel’s quietness. Part character study and part family saga, In This Sign is wholly steeped in the everyday, holding up a magnifier to Abel and Janice’s relationships with each other, with their children and grandchildren, with their employers, with their fellow parishioners at the deaf church, and with their in- laws. That’s not to say there isn’t tension in the novel. Over the course of it, I was often as gripped by these somewhat commonplace interactions—the friction between Janice and her coworkers due to her superior performance on the factory floor, or Janice and Abel’s first meeting with their son-in-law to-be—as I am while reading a thriller.

I spent a while trying to reverse-engineer this craft trick: How did Greenberg make the minutiae of our daily lives feel so monumental? Eventually I realized that through astute and wholly authentic observations, she had simply cultivated an intense empathy for Abel and Janice, which is to say it wasn’t a trick at all.

The quietness of In This Sign is, I think, one of the novel’s greatest successes, because it forces readers to reckon with the intricacies of deaf people as people, not only in big, trajectory-changing events, but mostly in the little moments. The hardships that Abel and Janice do experience aren’t because they’re deaf, but because they’re human and must contend with the full range of what it means to grow up and raise a family against the backdrop of a rapidly changing society.

I realized that through astute and wholly authentic observations, [Greenberg] had simply cultivated an intense empathy for Abel and Janice.

At times, these hardships are certainly made more difficult by the inaccessibility of the hearing world: a misunderstanding between Abel and a car salesman at the opening of the novel results in wage garnishing that further burdens the family financially in an economically tumultuous time. The pain of losing a child is made harsher and more humiliating in the struggle to communicate while coffin shopping. Because of this, some readers have criticized the portrayal of Abel as “ignorant” and Janice as quick to anger for casting deaf people in a negative light. And while it’s true—especially at the time of its first publication, when there were few portrayals of deaf characters—that some might mistake these characters’ struggles and failures as inherent to deafness itself, I don’t think that’s the book that Greenberg wrote.

Deafness isn’t a monolith; it would be unfair to ask any writer or character to fully embody a deaf perspective. And what’s more, Greenberg’s care in foregrounding Abel’s language deprivation and the failures of oral education makes it clear that his and Janice’s confusion over and mistrust of the hearing world are not character flaws but the result of a deeply flawed system designed to crush them. Today’s readers, encountering Abel and Janice amid a more robust backdrop of deaf literature, including works by deaf writers, will be even better positioned to appreciate the complexity, the humanity, and the ugliness in In This Sign’s pages.

Through the eyes of their hearing daughter, Margaret, we also see moments when Abel and Janice’s limitations are self-imposed: Abel buys himself a hearing aid (which he wears and dislikes) as a gift for Margaret, thinking she’d find him more presentable, when the electronic gift that Margaret is really pining for is a radio. Janice feels self-conscious in both the hearing and deaf worlds, worried about being seen signing at the factory, and afraid for the family to attend the deaf church without the “right” clothing. These failures are important because they’re specific to the characters’ own personalities and ideologies rather than indicative of deafness. In a literary world of so many Tiny Tims, I appreciate that Abel and Janice are sometimes unlikeable. Greenberg respects her characters enough to craft fully realized human beings, warts and all.

It’s undeniable that Janice’s and Abel’s lives are not exactly beautiful, marked often by strain and struggle. But if all the hardships and slights they endure at the hands of hearing people are upsetting, I’d implore readers to see these injustices as a call to action—to advocate tirelessly for an education system that, instead of providing deaf children with the veneer of inclusive education, gives them the robust linguistic and academic skills they’ll need for a safe and successful future. A call to action to stand in solidarity with the deaf community, whose self-determination remains under attack.

Today, pure oralism, now rebranded as “Listening Spoken Language approach” (LSL), still exists as a powerful force in deaf education, perpetuating isolation and cognitive damage through language deprivation that doesn’t look much different from what Abel might have experienced nearly a hundred years earlier. In this way, it’s unfortunate that Greenberg’s novel has stood the test of time.

Ultimately, though, if Greenberg has pulled back the curtain on the suffering of disabled people in an oppressive society, she has also given us the answer for how to overcome it. In the final pages of the novel, we see Abel, Janice, and their grown daughter chatting; together they laugh, and it’s clear that this novel isn’t only one of deaf hardship, but also one of bravery and great joy. Margaret’s son, Marshall, has left home to join the civil rights movement, and the three discuss what he might be hoping to achieve.

“He wants us to end poverty and despair,” Margaret says. Abel, whose once halting sign is now described as “elegant,” says proudly, “we did that.” When Margaret explains that Marshall is thinking of change on a larger scale, Abel and Janice suggest the solution must be something “like Sign”— sweeping and propulsive, passed down and across generations with both care and urgency: the thing that changed their lives, and made its users rich.

__________________________________

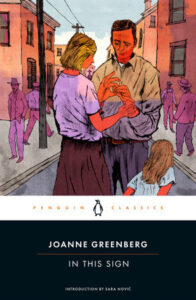

From In This Sign by Joanne Greenberg. Introduction copyright © 2024 by Sara Nović. Available from Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Sara Nović

Sara Nović is the author of the New York Times bestseller True Biz and Girl at War, which won the American Library Association’s Alex Award and was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She holds an MFA from Columbia University, where she studied fiction and literary translation, and is an instructor of Deaf studies and creative writing. She lives in Philadelphia with her family.