Shirley Chisholm on Why She Ran for President

“I ran because someone had to do it first.”

It was strange that some of the people screaming the loudest were Wallace delegates with long red, white and blue neckties. One little white man kept jumping up and down; he didn’t stop during the ten minutes it took for my acceptance speech. Little of the enthusiasm spread to the rostrum, though. Party chairman Larry O’Brien and the other officers at the Democratic National Convention in July, 1972, were impassive. It was an odd contrast; I noticed it fleetingly as I walked to the microphone.

There was no speech prepared. I didn’t need one, because there was only one thing for me to say: “Brothers and sisters! At last I’ve reached this spot!” I don’t remember my exact words. There are tape recordings somewhere, probably, for anyone who thinks the exact words matter. The placards waved, a band played, the hall was a stormy beach with waves made of people dressed in all colors, and their shouts were like the noise of an ocean. I had never seen a national convention session before except on television. State ones, yes. But the only convention I had gone to was the 1968 one in Chicago, and that was neither as a candidate nor as a delegate; when the session was nearly over I went to attend a meeting of the Democratic National Committee.

As I left my trailer behind the hall in Miami, surrounded by a ring of Secret Service men, I felt no excitement. Backstage, watching the scene on a television set until it was time to go on, I was still calm. But now this huge room was pulsing and jumping at me, so much more than I had expected. How long it went on, I could never tell. Even when I began to speak, they never really quieted down. If you had just landed from the moon, you might have thought that I was the convention’s choice, not just a preliminary to the main event. I tried to focus on something and get myself together. People were leaving their seats, pushing through the chairs to the aisle below the speakers’ platform, where I stood behind a huge-seeming lectern.

Almost everybody was applauding and cheering—everybody except some of the Mc-Govern delegates, who had contented themselves with a few claps. What I noticed most were the older black men and women. Some were crying, and their faces were so full of joy that they looked in pain. I thought I could read their lives’ experiences in their faces at that instant, and I know what it was they felt. For a moment they really believed it: “We have overcome!”

What I said that night was that most people had thought I would never stand there, in that place, but there I was. All the odds had been against it, right up to the end. I never blamed anyone for doubting. The Presidency is for white males. No one was ready to take a black woman seriously as a candidate. It was not time yet for a black to run, let alone a woman, and certainly not for someone who was both. Someday . . . but not yet. Someday the country would be ready. Those were the things I had been told, everywhere I went for ten months, even before I announced officially that I was a candidate, and everywhere I was asked the same question: “But, Mrs. Chisholm—are you a serious candidate?” Each time, trying not to lose patience, I explained, and tonight I was explaining again.

I ran because most people think the country is not ready for a black candidate, not ready for a woman candidate.

Of course my candidacy had no chance. I had little money and no way of raising the funds it takes to run for high office. I had no big party figures supporting me. To the extent that they noticed me at all, the movers and shakers wished only that I would go away. A wild card, a random factor that might upset some detail of their plans, an intruder into the real contest among the white male candidates. Their response was ridicule—in private, not in public, because a gentleman doesn’t make fun of a lady and a politician doesn’t want to risk losing the black vote. But their attitude came through clearly: treat her with respect, but of course you don’t have to take her seriously. If they ever wondered why I was running, their explanation was usually “Chisholm is on an ego trip.”

So I did not devote my acceptance speech to a discussion of “the issues.” I had discussed the issues before. People hear about the issues from every politician who gets up on a stump. They’ve quit listening to the traditional speeches with the traditional promises. “Fellow Americans, these are the great issues we must face. Fellow Americans, this is what I will do for you if you elect me.” So what’s new?

Who are you, and where are you coming from? Those are the questions people want to hear answered now. The old routine worked for a long, long time, but its time is done. I had no promises to make anyway, because I was not about to be the nominee. I had something more important to explain: why I was there. I’m still explaining it.

I ran because someone had to do it first. In this country everybody is supposed to be able to run for President, but that’s never been really true. I ran because most people think the country is not ready for a black candidate, not ready for a woman candidate. Someday . . .

It was time in 1972 to make that someday come and, partly through a series of accidents that might never recur, it seemed to me that I was the best fitted to try. Once I was in the campaign, I had to stay all the way to the end, all the way to that night at the convention. Nothing less would have shown that I was “a serious candidate.” If there had been only ten delegates ready to vote for me on the first ballot, instead of more than 150, I would still have stuck it out. The next time a woman runs, or a black, a Jew or anyone from a group that the country is “not ready” to elect to its highest office, I believe he or she will be taken seriously from the start. The door is not open yet, but it is ajar.

__________________________________

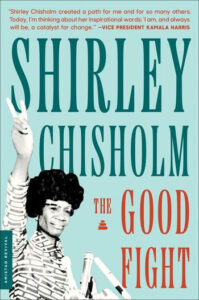

Credit line: Excerpted from The Good Fight. Copyright © 1973 by Shirley Chisholm. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins. First HarperCollins paperback published in 2022.

Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Chisholm was the first black woman elected to the U.S. Congress in 1969 and was re-elected six times until she retired in 1983. While in office, she spoke out for civil rights and women’s rights, advocated for the poor, and opposed the Vietnam War. In 1972, she was the first African American person to run for the Democratic Nomination for President of the United States. In 2015, she was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. Chisholm wrote the autobiographical works Unbought and Unbossed (1970) and The Good Fight (1973).