The following essay appears in full in the Spring 2015 issue of Zyzzyva.

1. A press conference.

It’s January 2013, and I’m watching some political theater on C-SPAN’s website. Senator Charles Schumer leans over a podium in a Senate pressroom. His glasses sit low on his nose, and he looks more like one of my great uncles than someone reading a policy statement to assembled reporters. But he and seven other senators have hammered out an immigration reform proposal, so this is News. “We still have a long way to go,” he says, “but this bipartisan blueprint is a major breakthrough.”

I take Senator Schumer’s announcement personally. Over the years, I’ve known many people who’ve been in the United States when the law said they shouldn’t be. I’m a public interest lawyer, but I’m not talking about clients. My list includes friends, my husband, and even my father’s mother and aunt, who as teenagers landed at Ellis Island with documents that weren’t their own. Crowded in the steamer’s steerage hull, they must have wondered, “Will it work?”

My great-aunt and grandmother’s papers weren’t doctored or stolen, though—they’d switched with each other. Aunt Mary had stopped growing after falling from a tree, and her family was afraid she’d be rejected at the border as physically defective. Her parents decided she should pretend to be younger, hence the paper switch with my grandmother, her younger sister. The trick worked. My grandmother and Aunt Mary both made it into the U.S. and wound up working in the garment factories. My grandmother, who could sew anything, left the garment shops to raise her family, but Aunt Mary kept working, sealing box after box, inserting slips of paper atop the folded clothing: “Inspected by Number 9.” When finally it came time to retire, she asked my father for help with her Social Security application and handed him a clutch of documents. Each showed a different birthday. My father settled on one, and she started getting her checks.

“She was such a dear woman,” my father says. Holding his hand just above his abdomen, he adds, “She was only about this tall.”

I never met Aunt Mary, so all I know about her is that she was a tiny, unassuming woman who once did something brave and illegal, abetted by my grandmother. People leap into acts such as these when they know the rules don’t favor their survival but they want to live anyway. I have many friends who, like Aunt Mary, did whatever it took to get into the U.S. They plodded through the desert, scrambled over fences, convinced border inspectors at the airport that they were coming as tourists, not to stay. One friend spent the night in a safe house in Tijuana, where she met women who were fleeing the civil war in El Salvador and had traded sex for rides all the way through Mexico.

Then there was an acquaintance who told me his family’s story through choking tears. He and his brother-in-law were entering the country at El Paso, because both lived in the United States with valid papers. The rest of the family was crossing illegally, away from the border checkpoint. “Whose bag is that?” the officer asked the man and his brother-in-law, seeing a purse left on one of the seats.

“My mother left it by accident,” the brother-in-law said, as if she’d forgotten the bag while sending the young men off on their journey. “A woman never just leaves her purse,” said the officer.

But, in the rush to cross with the coyotes, she had left it in the van. His face red with panic, the brother-in-law explained, “I haven’t seen her for fifteen years.” He’d been living in central Washington, and she in a small town in Jalisco.

The officer took pity and said, “Hurry and find her before she gets caught.”

This family was lucky, and some other friends of mine have been lucky, too, falling through one trapdoor or another in our immigration law. They got their papers and eventually became U.S. citizens. But many of my friends haven’t had that chance. They’re still waiting.

So when I see Charles Schumer on my screen, I hope he understands. His proposal comes with a catch, though. The border would have to be stamped secure before anyone could get their papers. By June 2013, Senator Schumer and his colleagues have come up with a bill, which includes border enforcement metrics and timetables; an amendment adds fencing, high- tech surveillance, and electronic identity checks in workplaces—hardly a surprise as the title of the bill starts with the term “border security.”

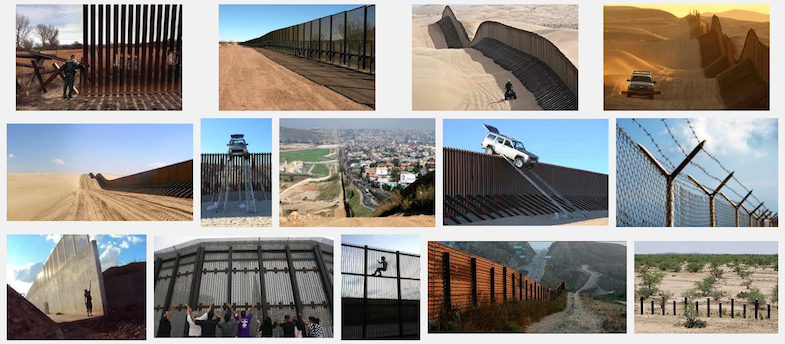

But perhaps the tripwires and sensors are props in a border security dream, rather than a depiction of border security reality. As I write this essay, I run an online search and pull up images of the border that show corrugated metal fence cutting through the desert. That fence is the picture we put to the word “border,” helping us believe in it as something real and constant, if vulnerable. It provides a place for the border, which the border needs if it’s going to mark the line we think it marks. We want the border to be clear and provide clarity. For almost twenty years, though, I’ve been trying to figure out where the border is and what it does, and I still don’t know.

2. Seeking asylum, filling out forms.

I didn’t grow up thinking of my family as refugees, but of course they were.

“They didn’t want to be drafted into the czar’s army,” I was told, or, “pogroms,” or “Grandpa’s older brothers and sister were revolutionaries.”

My family came with the stink of oppression on them. By the 1960s, we were upper middle-class, and I assumed that all American families followed this trajectory: the arc of the moral universe bends toward the suburbs. In those suburbs, my parents retained a sense of liberal responsibility. My father, a doctor, joined the nuclear disarmament movement and gave sidewalk talks on the medical effects of thermonuclear war. My mother opposed U.S. Cold War military interventions and on a file cabinet placed a bumper sticker that read, “El Salvador is Spanish for Vietnam.” It wasn’t really, but from this I understood that El Salvador was more than just a far-flung place.

In the 1980s, El Salvador was steeped in a civil war in which the Salvadoran government committed massacres, tortured and disappeared its victims, fired on demonstrators, and murdered priests, nuns, and union members. I learned from my mother that our government was sending military advisors and supporting government death squads, which she thought we shouldn’t do. People were streaming from El Salvador by the tens of thousands, but my mother didn’t tell me about these refugees, because they weren’t arriving in the Philadelphia suburbs. I wouldn’t meet any until years later, when I helped a few apply for asylum.

That happened in 1994. I’d recently graduated from college and moved to Seattle. My boyfriend—now my husband—had come to the city from northern Mexico, and he found an apartment above the restaurant where he worked. The building was shabby, with second-story front doors along the balcony, motel-style, and access to the interior hallway (and laundry machines) through doors that opened directly into the apartments’ bathrooms.

I was working as a receptionist, and one day I saw a poster for an organization called the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project (NWIRP), which provided legal services to immigrants. I called to see about volunteering. “We’ve got a training coming up,” the executive director told me. “Come by on Saturday.”

A paralegal, Julie, gathered us in the office’s dim conference room and taught us the basics of asylum law, showed us how to complete the forms, and told us what questions to ask the people we’d interview. She seemed to know everything. She explained that the circumstances of these asylum applications were unusual. Because the U.S. had backed the Salvadoran government—pressed it to continue the war, even—Salvadoran refugees had a very hard time getting asylum when they’d reached the United States. In fact, in the 1980s, immigration officials denied 97 percent of Salvadorans’ applications, even with all the murder and torture: bloody Cold War politics. Refugees and church groups sued, and the government finally agreed to give them another chance to apply.

The next weekend, I started interviewing applicants. The NWIRP headquarters was packed with men, women, children. I called the next person on the list into one of the offices and started asking all sorts of questions to make the application as strong as possible: the more terror a person had seen the better. But my interviewees didn’t easily produce stories of brutality. When I asked, “Why did you leave El Salvador?” they usually said, “Well, because of the war, like everyone else.” I didn’t know how to get them to say more, or know if there was more for them to say.

Across the hall, Julie stood in another office, tilting toward a seated client. She was saying, or I thought I heard her say, “Don’t you remember anything? You must remember something.”

She had a way of shaking out recollections. Maybe the Salvadorans’ memories lay beneath a tough rind of trauma that needed to be torn open. Or maybe they’d come to see horror as ordinary, not worthy of note. Either way, I learned that you can’t tell what people have been through by just looking at them. None of the people I interviewed came in maimed or disfigured, except for one man who was missing the top half of his middle finger. Instead of the digit, he had a smooth blossom of knuckle. He hadn’t lost the finger in the war, though. It had been lopped off when he’d reached his hand out of a moving car and caught it on a wire. I took his fingerprints for the application, and Julie told me to write in “missing finger” in the box where the print should have gone. The man and I shared a laugh over that. I was twenty-four when I did those interviews. Since then, I’ve met countless people who’ve been through hard things. I’ve met gay men raped by police in Latin America, Jamaican sugarcane cutters nickeled and dimed by rich growers in Florida, a woman who shot her stepfather, a woman who killed her own child in a drug fury. You learn to speak with people about difficult experiences.

But in 1994, all this was new for me. I began to get the hang of it, and when a Salvadoran interviewee said, “I just left because of the war,” I’d ask, “Did guerrillas or soldiers ever come to your house? Was anyone in your family ever killed?” And sometimes this helped people remember, and they’d say, “Oh, yes, there was that time …” I wrote in the answers, and in my memories I picture my interviewee and me in the dusty air of a dingy office, leaning over the application to review it together. The word “alien” appeared on the application in clear black letters, but I didn’t think of the Salvadorans as aliens. If an army bombs a person’s town with weapons provided by the United States, aided by training in the U.S., doesn’t that person have a relationship with the United States? How can we talk about that person as an alien, if there’s no border between us that really counts?

3. Making our map.

And yet we have maps that neatly mark the boundaries and make them real.

But: there are parts of the United States that don’t appear on most maps of the United States. Pull up a map online, and you’ll get the contiguous forty-eight with Alaska and Hawaii shifted to the southwestern flank, as if pushed there by a finger of godlike proportions. You don’t see Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, or the other “unincorporated territories” of the United States. Although these places belong to our country—whatever the word “belong” may mean—the godlike finger has not moved them within our sight line.

Which takes me to a photograph I’ve downloaded from the National Archives. In the photo, Teddy Roosevelt stands atop San Juan Hill in Cuba in 1898, surrounded by his Rough Riders. They’ve just overrun Spanish forces, having advanced behind a line of Gatling gun fire. They moved, in Lt. John Pershing’s words, “as coolly as though the buzzing of bullets was the humming of bees.” Now they’re posing for a photograph to portray their glory. That’s fine as far as capturing the triumph of that battle goes, but the photo also raises the question of border control. Because of the Spanish American War, the U.S. border was shifting again, and no one knew where it would make landfall.

It was the end of the nineteenth century, and the United States had taken it upon itself to liberate Cuba from Spanish tyranny. By the war’s close, we had a new set of territories, among them the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba. President McKinley couldn’t locate these places on a map, but the country still had to decide what to do with them. Should they eventually join the U.S. on equal footing with the states? Should they be treated like nations-but-not-quite-nations, as with the American Indians? Or should the U.S. just cast the new colonies off right away?

These questions concerned the identity of the United States, a country founded on the idea of self-rule, and they weren’t easy to answer. Political leaders and legal scholars began developing proposals and examining the Constitution, while Congress held heated debates. The Anti-Imperialist League roused a crowd of ten thousand at its convention in Chicago, where Massachusetts Senator George Hoar warned the country against descending into “the modern swamp and cesspool of imperialism.” At that point, he thought we still had hope.

The history of the border is a history of imagination. It’s a matter of who has the power to impose their imagination on the other.

But scholar Abbott Lawrence Lowell, future president of Harvard, where he was a professor of government, believed this hope was misplaced: the anti-imperialists had misperceived the essential nature of the U.S. “[T]here has never been a time, since the adoption of the first ordinance for the government of the Northwest Territory in 1784,” he reminded his readers, “when the United States has not had colonies.”

Yet Lowell still saw something different about the new possessions that meant they couldn’t just be fed into the country’s mill of expansion. “The settlers in the West carried with them the laws and customs of the East, and the precious habit of self-government,” he wrote in 1899 in the Atlantic Monthly. Puerto Rico and the Philippines: they were filled with people different from those settlers, who were us. They had no history of self-rule, and, being insufficiently civilized, couldn’t bear the burden of it. It would be “sheer cruelty” to foist it on the Filipinos, Lowell warned, and even for the Puerto Ricans, “self-government must be gradual and tentative.”

The year Lowell’s words were published, my family lived in czarist Russia. We weren’t yet part of this us. Still, in 2014, I can sit at my desk, sort through Lowell’s article, and wonder, as an American: what was it like for us to question the nature of our country in the wake of those foreign invasions? A century later, we have more experience with this sort of thing. We know that occupying Iraq for eight years doesn’t mean Iraq is part of the United States, and it doesn’t mean Iraqis become Americans. We can enact our will on people without feeling like those actions shift our borders. This wasn’t always so clear, and the debates continued. In 1901, fruit merchant Samuel Downes walked into this open question when he attempted to receive a shipment of oranges from the Port of New York. Downes was a founding officer of the city’s Wholesale Fruit and Produce Association and a donor to the Five Points Mission. Probably he was a businessman of some influence in the city.

However, when he tried to get his oranges—thirty-three boxes shipped from Puerto Rico—he learned that customs was charging him $659.35 in import duties. He protested: Puerto Rico was part of the United States. But the customs officials didn’t agree, so, instead of letting his oranges rot, Downes paid the duties and hired a lawyer, Frederic Coudert, who’d been gathering test cases to take to the Supreme Court. Coudert planned to argue that Puerto Rico belonged to the U.S., and the Constitution barred customs officials from treating it any differently.

Much was at stake in the decision—and not just national identity. Oranges and other commodities meant big money, so while almost no one knows about Downes v. Bidwell now, the case was a national event back in 1901. When it got out that the court was about to announce its ruling, spectators swarmed into the courtroom, eager for the decision.

The justices issued a ruling that continues to confound. For one thing, the decision had no clear majority and was cobbled together from a series of concurring opinions. For another, the justices decided Puerto Rico may belong to the United States, but that doesn’t make Puerto Rico part of the United States. In the decision’s most famous phrase, Justice White called the island “foreign to the United States in a domestic sense,” and I don’t know how any cartographer could express that paradox on a map, godlike finger or not. At any rate, Samuel Downes wouldn’t get his $659.35 back. The duty remained on the oranges, which were foreign.

But what about the Puerto Ricans? Were they also foreign?

This takes us to the case of Isabel González, chronicled by legal historian Sam Erman. In 1902, González sailed to New York in search of her errant fiancé, who was working at a linoleum plant on Staten Island. When she landed at the Port of New York, she was pregnant—making her sexually suspect in addition to racially undesirable—so port officials wanted to block her from entering as an “indigent immigrant.” She found herself in the middle of the debate over the status of Puerto Ricans, and she took a position, arguing that she was a United States citizen. Even after she married her fiancé and became eligible to enter the U.S. through this marriage, she kept it secret so she could pursue her case.

A federal appeals court declared her an alien. Coudert, Downes’ lawyer, wrote, “[A]s the law stands to-day, we have a new and seemingly paradoxical legal category of ‘American Aliens.’” He represented Gonzalez before the Supreme Court, arguing, Erman writes, that because U.S. citizenship really didn’t guarantee much in the way of rights, there was no reason to deny it to the Puerto Ricans. The court wasn’t willing to go that far. It declared that González wasn’t an alien, but she wasn’t a citizen, either.

It took fifteen years for Congress to extend citizenship—statutory citizenship, meaning not guaranteed by the Constitution—to Puerto Ricans, and President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill on March 2, 1917. Later that month Puerto Rico’s appointed governor, Arthur Yager, appeared before the island’s legislators and addressed them as “fellow citizens of the United States.”

“I welcome you into our great national family with high hopes,” the New York Times reports him as saying, and I imagine him standing grandly at the podium, arms spread wide in imperial embrace.

That November, Governor Yager gathered at San Juan’s Municipal Theater with his daughter, the president of the House of Delegates, and other political and military leaders. They were there to draw eight thousand draft numbers for World War I, making a public ceremony of conscription. Miss Yager picked the first number. The Puerto Ricans went off to war, but the island still wasn’t fully part of the United States and isn’t to this day. You may find Puerto Rico on some U.S. maps, at the tail end of a string of Caribbean islands. It will be marked as “Puerto Rico (U.S.).”

4. Origin stories.

No matter what dangers my family escaped in the early twentieth century, they couldn’t have predicted the greatest danger, which probably would have consumed them had they stayed in Europe. Just as there are still Jews despite genocide, there are still Indians. (When I was a child the idea of an Indian seemed magical to me. In one of my earliest memories, I’m sitting with my family at a Phillies game in Veterans Stadium, plastic seats crummy with peanut-shell dust, when my father says, “I think that man over there is an American Indian.” I searched for the Indian in the stands, but if I saw him I don’t remember it; I recall only the feeling of fascination and surprise. There were still Indians! Now I wonder if some Nazis dreamed of the day that a few leftover Jews would fascinate rather than repel—but I shouldn’t stretch this comparison, because like unhappy families each genocide is genocidal in its own way.)

We could ask many questions about our American genocide, among them questions about borders. On state maps now, sometimes you’ll see the boundaries of reservations marked out, and sometimes you won’t. This points to the unsettled status of Native nations. They’re sovereign nations, but they’re also tangled up in jurisdictional confusion—among the tribes, states, and federal governments—that compromises self-government and, to outsiders, may make them seem like something less. One example is that tribal courts may not prosecute non-Indians who commit crimes in their territory.When the victims are Indians, the federal government is supposed to handle these crimes, such as rape, but it has a history of overlooking them, so it’s as if every non-Native American on a reservation carries diplomatic immunity. In 2015, the law is changing. Native courts will be able to try non-Indians for some crimes of intimate violence against Indians, which seems like a good development, but it doesn’t make jurisdiction entirely clear—jurisdiction and territory still won’t be the same thing, as we often assume they are.

It’s impossible to separate violence from the writing and rewriting of borders. In 1831, amid machinations to expel the “Five Civilized Tribes” from the South, the Supreme Court decided it couldn’t hear a case brought by the Cherokees, who were challenging Georgia’s right to extend state law to their territory. The court’s refusal to hear the Cherokee claim rested on an interpretation of geography. Chief Justice John Marshall wrote, “The Indian Territory is admitted to compose a part of the United States. In all our maps, geographical treatises, histories, and laws, it is so considered.” And so, the court determined, the Cherokee represented not a “foreign state” but a “domestic, dependent nation” lacking the right to sue Georgia in U.S. courts. If a border existed between the Cherokee Nation and Georgia, in this instance it couldn’t keep Georgia out.

I’m looking at another photograph from the National Archives. It depicts the delegation led by Spotted Tail, a Sicangu Lakota leader, to Washington, D.C. The official record indicates the photo was taken sometime between 1871 and 1907, but since Spotted Tail was killed by Crow Dog in 1881 the date range must be too broad. I don’t know who else appears in the photo or what Spotted Tail and his delegation were doing in D.C. I’ve only just learned that he ever existed, and all I see in this photograph of bygone Indians—with their moccasins, blankets, braided hair, and pipes—is a representation of inevitability, which is my fault and not theirs.

Spotted Tail was born eight years before the Cherokee Nation v. Georgia decision. Crow Dog, the man who killed him, was born just a couple of years after. Both came to live on the Great Sioux Reservation decades later, following years of war. Spotted Tail had been imprisoned in Fort Leavenworth after fighting in the Sioux War of 1855. Traveling to the fort under military guard, he passed by so many white farms and towns that he came to believe there was no way to defeat the United States. Crow Dog had fought against the U.S., too, and he also had to make his peace, although I can’t fathom how complicated it must be for a person to negotiate with a society that has committed genocide against him.

The peace treaty that created the Great Sioux Reservation (and set its boundaries) was a nation-to-nation agreement, but it put the U.S. government deep into territory that supposedly wasn’t within U.S. jurisdiction. There would be a U.S. Indian agent on the reservation and an agency office, along with a school, buildings for a carpenter and blacksmith, and provisions to turn the Indians into farmers.

In the end, Crow Dog and Spotted Tail both wound up living here and assuming roles of political leadership. Crow Dog became a tribal police captain. Spotted Tail, a chief, carried a rifle and threw his weight around. He removed Crow Dog from his position twice, and Crow Dog may have suspected Spotted Tail of pocketing tribal money. There were factions, differences of opinion, tactics, and maneuvering. This is what I understand from my reading, although I can’t really understand—I’d have to travel to a different time, language, culture, set of politics.

But I can get a sense of the difficulties. Spotted Tail, Crow Dog, and other leaders had the railroad expansion bearing down on them, the crushing forces of assimilation policy, the U.S. Indian agent right there in his office, boring the American state into Lakota territory. Crow Dog is perceived as being less willing to make concessions to the Americans, Spotted Tail less reluctant.

Yet it will always be a mystery why, exactly, Crow Dog killed Spotted Tail that day. Spotted Tail had attended a tribal council meeting at the Rosebud Indian agency, where the council was planning another D.C. delegation, which Spotted Tail would head. When the meeting disbanded, he mounted his horse and started home. He saw Crow Dog crouched next to a wagon, apparently tying his moccasins but really lying in wait. Crow Dog raised his rifle and shot Spotted Tail through his left breast.

That’s one version of the event. In another I’ve read, the events go like this:

Crow Dog was fixing a bar above his wagon’s axle, while his wife, Pretty Camp, waited in the wagon with their child. Spotted Tail galloped toward them, stopped, and drew his pistol. Pretty Camp yelled a warning, and Crow Dog fired.

In both versions, the tribal council met the next day and, according to legal scholar Sidney Harring, ordered a payment to Spotted Tail’s family of $600, eight horses, and one blanket, which settled everything as far as the Lakota were concerned.

But even if they thought the case was closed, the story continued. In the killing of Spotted Tail, Harring explains, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) saw a test case for pushing its policy of assimilation and establishing criminal jurisdiction in Indian country. The BIA pressed the Attorney to prosecute Crow Dog—the idea being that he’d gotten away with murder—and he was sentenced to hang. With his legal fees paid by the BIA, Crow Dog petitioned the Supreme Court, and once again the court had geographic questions on its hands. Did the treaties and federal statutes allow the federal government to cross the border and convict one Indian for the murder of another? The court said they didn’t. As “aliens and strangers” in Indian country, they lived by their own laws—a victory for tribal sovereignty.

But the victory didn’t last. For one thing, a different sense of geography had taken hold among the citizens of the United States. “The Supreme Court has rendered a decision which will startle most readers,” the New York Times announced. “The decision is that there are persons living in the United States and not subject to the jurisdiction of any State or Federal Courts.”

I can’t imagine Crow Dog believed he was living in the United States, and he wasn’t, really—he was in Indian country—but it’s striking that two sets of people can look at the same piece of land and understand it so differently. This case, maybe more than any other, shows how much the history of the border is also a history of imagination. It’s a matter of who has the power to impose their imagination on the other.

The BIA and white reformers, who wanted the Indians fed into their civilizing machine, didn’t let the Supreme Court have the last word. They worked the legislative process, using Ex Parte Crow Dog as fodder. They had the Major Crimes Act slipped into an appropriations bill and won criminal jurisdiction after all, kicking off another reworking of geography. Ten years later, Congress decided to turn the reservations into individual plots, with “surplus” land to be sold off. The Supreme Court gave its approval in Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, which permitted Congress to reach into Indian land to administer it as it saw fit. Ninety million acres were absorbed into the United States, reservations rendered patchwork.

Through separate legislation, the Great Sioux Reservation was divided into several smaller reservations and whittled down. Crow Dog continued as a traditional leader, joined the Ghost Dance movement, and for years refused to accept his allotment.

I thought this would be the last I’d read about him, and then I came across a New York Times article from 1903. That was the year my grandfather was born in czarist Russia, the Supreme Court decided Lone Wolf, and the year after the U.S. defeated the Filipinos’ war for independence—a good time for empire. Crow Dog was about seventy and had just left the Rosebud Reservation for New York City. The Times headline announced: “Indians Call on Mayor; Mr. Low Cordially Greets Crow Dog, Who Bears Honors as an Assassin.”

Crow Dog had joined a delegation of fifteen Indians in traditional dress, and they stopped in on the mayor on their way to Coney Island, where they’d perform that summer for the city’s heat-drenched masses. An interpreter handled the introductions in the mayor’s office. “This is Crow Dog,” he said, “who assassinated Spotted Tail, chief of the Arapahoes, some years ago.” The mayor shook Crow Dog’s hand and, after enjoying the company of the costumed Indians, “bid them all adieu.”

PART 2 of “Shiftiness: The Border in Eight Cases” can be read here.

Julie Chinitz

Julie Chinitz has worked in public policy and community organizing since 2000 and is the former policy director at Alliance for a Just Society in Seattle.