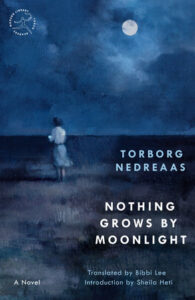

Sheila Heti on Torborg Nedreaas’s Nothing Grows by Moonlight

“Her life has been brutally severed multiple times by that unholy necessity: abortion.”

It’s a common story. A young, inexperienced girl falls in love with an older, more experienced man. He takes her virginity, lets her fall in love with him, but does not love her as exclusively, as fatally, as she loves him. She is left to wrestle with her overwhelming feelings of loneliness and passion—the most beautiful feelings a person can have, and the most painful ones. But in Nothing Grows By Moonlight, this common story immediately becomes a little less common, for this story is being told by a woman to a Man—a stranger—and it is the Man recounting her story to us.

Torborg Nedreaas’s Nothing Grows by Moonlight is presented as though we are reading the Girl’s speech, but really, we are reading her speech as the Man remembers it; it’s a paraphrasing. She often talks in circles, and interrupts herself, asking herself questions like, “What am I prattling on about?”

The way this Girl sounds—this is how men hear women. Women sound to men just like this: frantic, abbreviated, disjointed, dramatic, self-pitying, self-erasing, arrogant, pitiable, fragile, confusing, oblique.

After spending an entire night relaying her life story, the man notes that, “She stared ahead for a long time. Then she said in quite a low tone of voice: ‘This is where I should have started.’”

We’re left wondering: Was the Girl jumping backward and forward in time because she was really so afraid of boring him, and so unable to hold on to the main thread of her story? Maybe! But I also thought, The way this Girl sounds—this is how men hear women. Women sound to men just like this: frantic, abbreviated, disjointed, dramatic, self-pitying, self-erasing, arrogant, pitiable, fragile, confusing, oblique. A man can’t follow the train of a woman’s thought. He cannot grasp her throughline.

I wondered, What would this book be like if the listener had been a woman—an older woman, say, who’d had many of the same experiences as this “strange girl”? Probably, if the listener had been a woman, when she recounted the Girl’s speech, it would be a lot less exasperating, and a lot more clear, because she would have been far less surprised by the things she heard. So perhaps the confusion, the shock, the emotional distress we hear in the book’s voice belongs less to the Girl than to the Man.

After all, despite the story being told through his point of view, some of her phrases come through as perfect gems of understanding:

You know, it’s really wonderful to be a woman. Or should be.

There’s a lot left of the ape in us.

The result of all coercion is simply to make you bitterly fight it.

In the end it is probably money that determines morality.

It might be that all the hesitation and backtracking is the Man trying to grasp the reality of the female experience, trying to narrate an experience he had never before imagined, but which a woman—for the Girl is nearly forty—even if she never before spoke it out loud, could still not hold with such emotion or surprise.

And her life has been brutally severed multiple times by that unholy necessity: abortion.

As I read, I was considering how Nothing Grows by Moonlight could so rewardingly be read alongside Willful Disregard by the Swedish writer Lena Andersson, and Simple Passion by the French writer Annie Ernaux, and If Only by the Norwegian Vigdis Hjorth, who has cited Nedreaas as a forebearer of a tradition of “exceptional female writers” in Norway “whose works have changed our way of thinking about society.” These four novels create a convincing, wrenching, kaleidoscopic picture of the range and repetitions of the most fatal kind of love; the sort of love that allows nothing else to grow around it, that eradicates all dignity; a love which, in order to be completed, must be told.

Nedreaas’s Girl gradually reveals some inklings of a broader understanding of her situation: She’s not just hopelessly in love, but she’s a woman in the mid-twentieth century in love; she’s in love as a working-class person in a small town.

And her life has been brutally severed multiple times by that unholy necessity: abortion. Abortion is bound to poverty, as shame and disgrace are bound to having a woman’s body in a Christian world. Yet none of the Girl’s growing understanding can be acted on, because she is poor, because she is uneducated, and because she has fallen in the sort of love that ruins one’s capacity to connect in a beautiful way with any other person, or even a political or philosophic ideal. Her life has been nothing like the life of the Man she is addressing, we are sure of that.

What do we know of the Man who recounts her story? He is determined for us to believe that he does not feel any sexual attraction toward the Girl. This is, perhaps, proof of how well he listens, and why he can be trusted to recount her tale. But why does he stay awake, silently, all night long and oblige her? Why did she pick him?

He implies that it is because they both recognized the soul in the other, for the soul “only has meaning to those who also have a soul. A large segment of the human race has none.” So we suspend our sense of the strangeness about this night, for this night is the product of two souls meeting, not of the “human race” trudging through its social norms.

We sense that by hearing her story, the Man has lost his story and so lost his way. His story has been overshadowed by the Girl’s.

When two souls meet in the middle of the night, it’s the opposite of what the Girl’s lover says when he rejects her: “I know everything about you now. It’s over.” (This sentiment is comprehensible to us because the feeling of being in love lasts only as long as the mystery lasts, which is not forever.) Rather, the meaning of the late-night meeting at the heart of this book is: “I know nothing about you now. It’s begun.” True love lasts as long as the mystery lasts, and for True Love, the mystery never ends.

A woman steps upon the stage of a book (and a man’s life) and exits it silently at the end. She warns him, at the beginning, “You must reckon with the fact that I’m acting a little. Acting as in a play.” When she finishes her speech, the curtain comes down and the play is done.

So why, after thirteen days, is the Man still looking for her? Why can’t he accept that she’s gone? Does he have a taste for woman’s suffering? Has he fallen in love? Does he want to thank her, or learn more about her, or save her? Does he want to know if she’s alive or dead? Does he want to tell her his story? No—of all the possible answers, it’s impossible to imagine this last one.

We sense that by hearing her story, the Man has lost his story and so lost his way. His story has been overshadowed by the Girl’s. Maybe this is the best thing that can be achieved by a poor and disenfranchised Girl who has been obliterated by the world and by men—to tell a strange man her story, and so obliterate him; obliterate the possibility of him continuing with his life, for his life has been so completely filled with her life, it is as if he was impregnated by her tale.

The Girl thinks, upon her third pregnancy, “I didn’t want to ruin my body and soul one more time in order to kill the life that was growing inside me.” But she does. Yet through the course of one night, she succeeds in expelling her body and soul into the Man, into a vessel that is safer—that she hopes can carry the beautiful tragedy of her whole life.

__________________________________

From Nothing Grows by Moonlight. Used with the permission of the publisher, Modern Library Torchbearers, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2026 by Sheila Heti.

Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is the author of eleven books, including the novels Pure Colour, Motherhood, and How Should a Person Be?, which New York deemed one of the “New Classics” of the twenty-first century. She was named one of the “New Vanguard” by the New York Times book critics, who, along with a dozen other magazines and newspapers, chose Motherhood as a top book of 2018. Her books have been translated into twenty-four languages. She lives in Toronto.