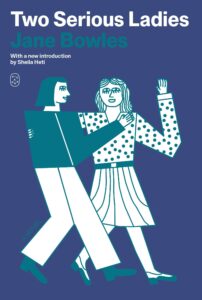

Sheila Heti on the Profound Influence of Jane Bowles on Her Writing—and Life

What “Two Serious Ladies” Can Teach Writers About Struggle and Bravery

When I first read Two Serious Ladies in my early twenties, it instantly and forever changed the way I wrote. It influenced me more than any book I can think of. I imagine it’s because I had not before read a voice that wasn’t pretending to understand more about life, or people, than could be understood. In other words, an authoritative voice that understood so little. And at the same time, so much!

Also, every line was funny in a deep, resonant, underground way—funny not in the completed, finished way of a joke, but in the compact, generative way of a seed. The humor was about what it was possible to know about humans and a human life. I loved it. I loved it so much that for the next twenty years, whenever anyone asked me for a recommendation, I told them to read Two Serious Ladies.

I always return to an image of Jane Bowles writing, which comes from A Little Original Sin, Millicent Dillon’s magnificent biography (you should read it!): “She would stand by the window a great deal. Then she’d sit and write a few lines, scratch them out, and go stand by the window again.” What a tireless, thoughtful worker!

I loved it so much that for the next twenty years, whenever anyone asked me for a recommendation, I told them to read Two Serious Ladies.

I imagined she was constantly scratching things out because of her need for precision. Two Serious Ladies reads like a dream, like something that unfurled effortlessly, but her experience of writing it seemed to be exactly the opposite. In a letter to Paul Bowles, her husband (although during their marriage, they both had lovers of their own sex), Jane compared herself to some of her contemporaries: Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Carson McCullers—who was very celebrated at the time, and three days older than Jane. She said that McCullers was “not really a serious writer. I am serious but I am isolated and my experience is probably of no interest at this point to anyone.”

It is worth noting that she compares herself to two philosophers. I think part of the reason the book was so difficult to write is because it is so philosophical. What does that mean? It means that she is trying to convey what she thinks life is, at its essence. Many novelists do, but her vision is more complex and difficult to fathom. Certainly she believes that humans have a religious duty, but to a shifting, elusive, personal religion, so their commitments must be continually improvised. She is in favor of making life difficult for oneself—self-denial and rigor are part of every religious calling—but if each person must make up their own rules, what one person morally requires of themselves might seem, to another person, like just a night of fun. (As Mrs. Copperfield explains to Arnold about her decision to visit the mainland: “It is not for fun that I am going, but because it is necessary to do so.”)

Jane Bowles’s sense of ethics has nothing to do with the greater good, or eradicating war or poverty, or helping other people. It has to do with personal tests and traps and a relationship to a self-made symbology. It is very hard to explain and, I think for her, was so hard to demonstrate that after writing this one novel, most of her powers were spent. (She also completed a handful of short stories and a play before dying young, at age fifty-six. Two Serious Ladies was published in 1943, when she was twenty-four.)

Talking about how hard she found her work, she wrote, “It is almost more than one can bear to be continually doubting one’s sincerity.” I think I understand: there is a tendency, when writing, to enjoy the sentences one is creating, whether or not they are saying something true, or are saying what you really believe. It is easier to simply amuse oneself. She elaborated in the same letter, “I think the part [of writing] I mind the most is this doubt about my entire experience.”

This helps explain the sense of struggle and bravery one gets from her book—and the struggle to be sincere (which is a funny struggle, in a way—what does it mean to be sincere in fiction, which is the practice of making things up?). And what is braver than for a person to write in the face of “doubt about [their] entire experience,” as she believably claimed she was doing—a variety of suffering that is easy for a reader to perceive.

[pullquoteWhat does it mean to be sincere in fiction, which is the practice of making things up?)[/pullquote]

Originally, the book was called Three Serious Ladies. When Jane showed the manuscript to Paul, he suggested cutting one of the ladies. There had been, according to Millicent Dillon, a minor character named Julia, “a prostitute who is afraid that she is dying and who can think of nothing but how she will escape punishment for her sins,” and a third serious lady, Señorita Córdoba, who “has but one goal in life: to own a dress shop in Paris.”

To allow these two drives to share the same stage—the perhaps trivial desire to own a dress shop in Paris, and the perhaps profound desire to escape punishment for one’s sins—would be enough. But Jane Bowles’s vision of life goes even further: she sees these drives as equally profound and trivial, which is a shocking proposition about what life is; specifically, what a woman’s life is.

Because, importantly, the book is about women—or rather, ladies. The surface problem with being a lady is that you have to do what is proper and right, while the more underground problem is that, because men organized the world for their own pleasure, one has to start from scratch in determining what is truly proper and right: the rules of society aren’t yours, and so can’t be abided, not if one wants to be “sincere.” This gives rise to the almost incomprehensible decisions the women in this book are constantly making: Why would you let a man you didn’t like live in your house with you? Well, why wouldn’t you?

Mrs. Copperfield, Miss Goering, Miss Gamelon, Pacifica, Mrs. Quill—they aren’t so much characters (they are too similar for that) as demonstrations of what it might look like for a woman to attempt to live sincerely, if living means that you are living for the first time. Of course, living does mean that you are living for the first time, but very few people (and fewer ladies) actually embrace that freedom, and I can think of no writer who tries so strenuously to present what that freedom might look like, moment by moment, thought by thought.

In some ways, I think the idea of a “serious lady” might even be a paradox, if to be serious means to understand the world according to one’s own precepts, experiences, and observations, and to behave in a way that reflects this. A lady, on the other hand, follows rules that others have devised. How, then, can a “serious lady” be anything other than a very peculiar and odd creature—which the women in this book certainly are?

It is unsurprising that Jane Bowles groups herself with two existentialist philosophers. What does it look like, for her, if a person truly embraces their freedom? It might look like one is being capricious, directionless, silly, dangerous, passionate, making random connections and unfathomable insights. It looks like a life in which one builds nothing. This existentialism is far from the heroic, politically committed, existentialist vision of Sartre and de Beauvoir.

It is, rather, an existentialist vision born out of utter detachment from any collective enterprise, a vision that sees no real overlap between any generally held truths, and one’s own private proclivities, which, if followed, might contribute nothing to the public good.

Jane Bowles once worried to Paul that the Surrealists would not like her. He told her biographer, “She was very aware of them and she felt left out. She thought they wouldn’t want to know her because she didn’t have any good surrealist ideas.” Certainly, the difference between them and Jane, the reason Jane did not “have any good surrealist ideas,” was because the Surrealists were trying to turn the world upside down: to reverse its meanings. This implies that they started with the sense that there was a comprehensible world to turn upside down, which was what animated their “surrealist ideas.” Their interventions were made for an audience who also had some starting sense of what the world was. Jane Bowles doesn’t seem to have had a starting sense of the world. I think she felt she had to build a starting world, sentence by scratched-out sentence. And the Surrealists weren’t interested in being “sincere.”

Many commonly held truths (at least commonly held in her circles) are questioned in this book. She was part of a bohemian set that valued travel and new experiences and fleeing routine and convention and safety. At one point, she has Arnold say to Miss Goering, “I don’t know why you find it so interesting and intellectual to seek out a new city.” Returning to the same point later, Miss Goering states:

“In order to work out my own little idea of salvation I really believe that it is necessary for me to live in some more tawdry place and particularly in some place where I was not born.”

“In my opinion,” said Miss Gamelon, “you could perfectly well work out your salvation during certain hours of the day without having to move everything.”

“No,” said Miss Goering, “that would not be in accordance with the spirit of the age.”

Miss Gamelon shifted in her chair.

“The spirit of the age, whatever that is,” she said, “I’m sure it can get along beautifully without you— probably would prefer it.”

So funny! So true! This must have been an argument Jane had with herself, her peers, and her husband, whom she accompanied to Tangier. Another scene in which she presses on the conventional ways we have of understanding people (as if humans were a knowable mass) is when the unhappy Mrs. Copperfield doesn’t want to go to Panama with her husband, because it would mean leaving her new friends, Mrs. Quill and Pacifica, behind:

“Listen, Copperfield,” Mrs. Quill had answered, “you go and have the time of your life in Panama. Don’t you think about us for one minute. Do you hear me? My, oh my, if I was young enough to be going to Panama City with my husband, I’d be wearing a different expression on my face than you are wearing now.”

“That means nothing to be going to Panama City with your husband,” Pacifica had insisted very firmly. “That does not mean that she is happy. Everyone likes to do different things.”

Jane Bowles makes a similar observation later in the book, when Mrs. Quill is trying to buy a souvenir for Pacifica. She tells the waiter that she wants some little trinket “specially marked with the name of the hotel.” When the waiter says that “most people don’t go in for that,” Mrs. Quill complains, “Must I always be told what other people do? I’ve had just about enough of it.”

At one point, Mrs. Copperfield states, “No one among my friends speaks any longer of character—and what interests us most, certainly, is finding out what we are like.” This perhaps sounds paradoxical at first: Surely a person’s character is what they are like? But no, for “character” is something too fixed, too unified, too comprehensible. It is something Freud believes in: that we come from somewhere, and become something, and this progress can be mapped.

Jane Bowles’s vision is more unsettling: there are different names, and these names are attached to different bodies, and these bodies find themselves in different locations on the earth, and they come into contact with other bodies for shorter or longer periods of time, and their actions cannot be predicted, and they cannot predict themselves. And to suppose that these bodies-with-names-in-places actually have something so romantic, so grand, as a character—well, that is an idea so conservative, only a Surrealist could love it.

I am still struggling to say why Jane Bowles had such a profound effect on me. I think I cannot truly know. Certainly it was encountering a book so glittering, so original, so profound, so witty, so charming, so contemporary, and so old, in which every sentence read as if it had been translated from some unknown tongue. But there is also the fundamental mystery of why we are drawn to what we are drawn to, which this book is all about. I still find it hard to identify a novelist as serious as Jane Bowles—if serious means taking nothing for granted. I had thought about starting this introduction by asking, “What are these ladies so serious about?” The answer, of course, is “everything.”

_________________________

Excerpted from Two Serious Ladies: A Novel by Jane Bowles. Originally published in 1943 by A. A. Knopf. First Picador paperback edition, 2025. Copyright © 1943 by Jane Bowles, renewed © 1976 by Paul Bowles. Introduction copyright © 2025 by Sheila Heti. All rights reserved.

Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is the author of eleven books, including the novels Pure Colour, Motherhood, and How Should a Person Be?, which New York deemed one of the “New Classics” of the twenty-first century. She was named one of the “New Vanguard” by the New York Times book critics, who, along with a dozen other magazines and newspapers, chose Motherhood as a top book of 2018. Her books have been translated into twenty-four languages. She lives in Toronto.