Sharon Gless on Her First Stage Appearance and Earning a Seven-Year Contract for Universal Studios

The Cagney & Lacey Star Considers How an Actors Life Can Change in a Matter of Hours

The most famous acting teacher in Hollywood in the 1970s, Estelle Harman, judged my audition to be in her class as “the worst performance” she’d ever had to sit through in her entire career.

I didn’t hear that brutal complaint until two decades and two Emmy awards later.

Even though she wasn’t impressed by my audition, Estelle accepted me into one of her acting classes. She may have done so out of deference to my uncle Jack. He had probably made a phone call to her on my behalf.

I was about five years older than most of the other students in her beginner class. I didn’t care. I just wanted to start my training. The class met on Thursdays from 2 to 6 pm.

Now that I had the acting class, I knew a secretarial job wouldn’t work out, as Estelle’s classes were during daytime hours. I needed some type of evening employment. My idea was to apply to be a bartender at the Bel Air Hotel, despite the fact that female bartenders were rare in the early 70s in LA.

I certainly knew how to enjoy drinks; I only had to learn how to make them.

The next morning my phone rang. “Sharon. This is Arthur Marks.”

Arthur Marks was a producer who had a prolific and rising career as a film director. I had met him through a previous job of mine.

He said: “I’m starting a new company, and I want you to come and work for me.”

I said, “Mr. Marks, thank you, but I can’t.”

He said, “Why not? You’re the best production secretary around.”

“You’ll laugh when I tell you.”

He said, “Go ahead. Tell me.”

“I’m going to be an actress.”

He said, “I’m not laughing. How will you support yourself until that happens?”

I told him, “My acting class is on Thursdays from two to six. I’ll have to get a night job.”

He said, “So, you’ve got Thursday afternoons off. And I’ll still pay you for the full week. Now what?”

I went to work for Arthur Marks’s new production company at General Service Studios in Hollywood on Las Palmas Avenue. He stayed true to his word. I took my acting class every Thursday afternoon for the next full year.

When Estelle passed away years later, I was starring in Cagney & Lacey. Her daughter Eden told me that her mother had changed the way she taught acting because of me. I was floored. Estelle believed in working from the outside in—through mannerisms and costuming—to develop a character. I instinctively worked from the inside out. It was all I had.

In 1972, a young playwright, Candy Carstensen, had written a two-act comedy called What’s What. It was a play within a play. She cast me in the ingenue role. There was no pay involved, and we only performed the play twice, at the Encino senior community center. The audience, composed of our family and friends, sat on folding chairs. We didn’t charge anybody.

I played a visually challenged actress who is playing a nurse who cares for an elderly male patient. On our opening night, I exited for a quick costume change. Too late, I realized that I was supposed to remain in my nurse’s uniform for the next scene. I tried to hurry back into the costume, but when my cue came, I was only half dressed. I didn’t have time to button up, so I held the nurse costume closed in front with my hands and made my entrance, my hair now a disheveled mess. It looked like the old man had had his way with me. The audience burst into laughter. The rest of the cast tried to hold it together. It was a big mistake that couldn’t have worked more in my favor if I had planned it.

My entire Los Angeles family came to see my first stage appearance. They called it my “school play.”

At one point, Candy came backstage and said, “There’s some man in the front row who keeps yelling out, “Bravo! Bravo!”

I peeked through the curtain. It was my dad.

I had no idea who else might be in the audience. I certainly didn’t expect the phone call I received Monday morning while at work.

“Sharon, my name is Orin Borsten, and I’m in publicity at Universal Studios. I saw you in your little play over the weekend. You’d be perfect for the lead in John Cassavetes’s new film, and I want you to meet Monique James, the head of our talent department.”

Every wannabe actor knew who Monique James was, so I thought it was a prank call from an acting classmate.

I laughed, saying, “Okay. Cut the bullshit. Who is this?”

He said, “I understand why you’re skeptical. Why don’t I have Miss James call you.”

I said, “Yes. Do that.”

I hung up the phone, incredulous that a classmate thought I would fall for that shit. I mean, please!

Five minutes later Monique James’s assistant called. She requested that I come to Universal Studios and meet with Monique, in person. I couldn’t believe it. I set the appointment and immediately called Orin Borsten to thank him for the connection. He asked me to please stop by his office after my meeting.

My first encounter with Miss James was brief but significant. Her short physical stature, owl-eye glasses, and sensible shoes belied the powerhouse confidence she exuded. I was both intimidated and in awe.

She requested that I prepare a short scene from a play for her to see, “preferably with a male actor.” Then she tapped her cigarette out in her full ashtray and stood up, signaling that it was time for me to leave.

I didn’t ask her what type of scene she wanted. She just said, “Call me when you’re ready and bring it in.”

As I promised, I went by Orin Borsten’s office.

He told me, “You’re a comedienne, but forget doing anything by Neil Simon. She has seen it all.”

Neil Simon was the most prolific Tony-winning playwright of my generation.

Orin gave me a play, After Haggerty, which was a recent comic romp he had seen onstage in London. “This has never been done in the US. Do act one, scene one.”

I went home and read over act one, scene one, and gave him a call. “Mr. Borsten, I can’t do this scene.”

“What? Why not?”

I told him why. “Every line has the word pussy or fuck in it.”

He laughed. “The hell you can’t do it. Find an acting partner and rehearse.”

I said okay. I found a very good actor, an older British man, who was working at General Service Studios. We rehearsed together for four months.

My phone rang at work one morning.

“Are you ever bringing in that scene?” It was Monique James.

I told her, “I want it to be letter perfect, Miss James. My uncle told me that you occasionally remember when it’s good. You never forget if it’s bad.”

I could almost hear her rolling her eyes on the other end of the line.

“Just bring it in,” she insisted.

Good or bad, she wanted to see the scene soon. My acting partner was available and graciously showed up to the audition, which was held in Claire Miller’s office. Claire was Monique’s assistant. I had heard through the grapevine that Monique held all auditions there so she had the option of getting up to leave whenever she wanted. Seated next to Monique was Eleanor Kilgallen. Monique and Eleanor had started the only female-owned talent agency in all of New York. They had signed Grace Kelly and Warren Beatty early on. Lew Wasserman at MCA talent agency bought them out and placed them under the MCA banner.

Because I was so naïve and had no experience outside of acting class, I didn’t realize that professional auditions were often yes or no.

A few years later MCA acquired Universal Studios. Monique James was given the title of Vice President, Head of Talent on the West Coast, and Eleanor was given the same title on the East Coast. They became the first two female vice presidents of MCA/Universal. They were magnetic and intimidating, each on their own, but even more so as a duo. Eleanor was tall and thin and sat with a straight spine, her hair perfectly sprayed into place, white gloves on her hands, a crucifix around her neck.

I announced the name of the play, and we did our scene. Since it had not been done in the United States, I took the liberty of changing some of the words in the scene to make them flow better from my American mouth. I thought it was a crafty thing to do and that no one would be the wiser about my rewrites.

Afterward, Eleanor Kilgallen said, “I saw the play last month in London, starring Billie Whitelaw.”

Oh, fuck.

I thought it was all over. I had taken liberties with a script and been caught. Monique and Eleanor stood up and walked toward the door.

Because I was so naïve and had no experience outside of acting class, I didn’t realize that professional auditions were often yes or no. They like you. They don’t like you. You never get helpful notes. No one has that kind of time. I called out to Monique before the door closed, “Excuse me, Miss James. No critique? Nothing?”

She turned only her head, momentarily, toward me, “No. I will speak with Orin.”

I thanked my acting partner and he left. Any hope I had of making an impression had dissolved. Claire was silent as I collected my belongings.

“I guess I blew it.”

“Go home and wait by your phone,” was Claire’s only response.

About a year later, I had the courage to ask Claire how she’d been so certain that Monique would call me.

She said, “Monique always carries a pencil with her. During most auditions, she turns the pencil over and over in her hand. But while you were doing your scene, she held the pencil still.”

It was interesting to hear in retrospect. But on the day of my audition I had no clue. I also had no choice but to go back to my secretarial job that afternoon. I walked in and Mr. Marks said, “Monique James just called. She wants you to come back this evening and meet with her.”

Right after work, I drove back to Universal. Monique wanted me to go to a producer’s office and read for a series role that night.

She said, “Whether or not you get this part, we’d like to offer you a seven-year contract.”

I was floored.

Monique James, the head of talent, wanted to sign me to be one of 15 contract players for Universal Studios! She held one of the most powerful and influential positions in Hollywood in the 1970s and 80s. You couldn’t buy her attention for any price. She wasn’t about to squander her reputation on a poor bet. She was counting on me to succeed. Me! Holy shit!

I went to audition for the producer. I’m pretty sure I was in a dreamlike state. I found out years later that he told Monique that I was dreadful.

Well, you know me. Go big or go home!

Thankfully, I was none the wiser to his response regarding my audition, and Monique James let his apparent complaint go in one ear and out the other. She had made up her mind to sign me. I would be making $186 a week, guaranteed, whether I worked or not. My life had changed in a matter of hours.

I thanked her over and over. She responded by saying, “I have a feeling you’ve been acting your entire life. Now we’re just going to pay you for it.”

__________________________________

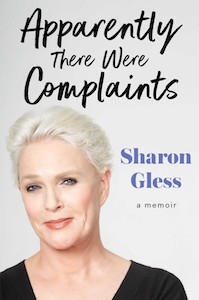

Excerpted from Apparently There Were Complaints. Used with the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Sharon Gless.

Sharon Gless

Sharon Gless was born into a prominent Hollywood family and always knew she wanted to be an actress. She was an exclusive contract player for Universal Studios from 1972 until 1982, when the studio ended all talent contracts. She was the last contract player in the history of Hollywood. While at Universal, Gless appeared on series such as The Rockford Files; The Bob Newhart Show; and Marcus Welby, MD, among others. In 1982, she accepted the role of Cagney in Cagney and Lacey, eventually winning two Emmy Awards and a Golden Globe Award for Best Leading Actress in a Drama Series.