Sex, Feminism, and the Lost Genius of Violette Leduc

On Her Newly Translated Classic, 'Therese and Isabelle'

Violette Leduc’s Thérèse and Isabelle is a story of marginalized love that has itself been marginalized. Shrouded by censorship laws since the 1950s, Thérèse and Isabelle, just published by the Feminist Press, is now completely unexpurgated and available to a US audience for the first time. Called “the most interesting woman I know” by revolutionary feminist Simone de Beauvoir, Leduc garnered much support from notable fellow writers, including Albert Camus and Jean Genet. However, her success was that of a “writer’s writer”—championed and read by a distinguished few. Her separation was not solely due to her erotic or homosexual content, as writers such as Genet received acclaim while covering such illicit subjects. It was the combination of her fierce independence and her fearless description of lesbian relationships that proved too uncomfortable for the male publishers of the time and too controversial for a greater audience.

* * * *

Publishing literature in translation is often about filling in gaps, about offering readers a richer historical tableau. This is certainly the case with the Feminist Press’s recent publication of Violette Leduc’s Thérèse and Isabelle, translated by Sophie Lewis in 2012 but written in 1955. Note that I say “written” and not “published”; this is because the 150-odd pages were originally meant to be the opening section of Leduc’s novel Ravages, but her publisher deemed the content (more on that shortly) too risqué and too explicit, even for relatively enlightened French readers. In fact, the pages weren’t even published in France for another eleven years. So the French, too, had to fill in a certain gap in their own literary history.

Here in the US, similar books by Colette, Simone de Beauvoir, Hélène Cixous, Monique Wittig, and Virginie Despentes have been available for years, many published in English not long after they appeared in French. Leduc’s most famous book, her literary memoir The Bastard (La Bâtarde), was published in English soon after it was nominated for the esteemed Prix Goncourt in France. For whatever reason, Thérèse and Isabelle, swirling with controversy and eroticism—two things that certain American publishers have always been attracted to—was ignored. Until now, when the Feminist Press saw the importance of the book and made sure English readers could appreciate it, too. As a bookseller, and especially as a bookseller with an interest in promoting books that expand people’s understanding of humanity in all of its multitudinous manifestations, I, for one, am grateful that this particular gap has been addressed.

About the content—the plot itself is simple: two female boarding school students have a passionate love affair. This was not, even then, a particularly shocking subject on which to base a story. French literature is rife with lesbian love stories, including well-respected and widely read books by the likes of Honoré de Balzac and Guy de Maupassant. Those, of course, were written by men who’d already written thousands of pages of rather traditional fiction, and the lesbian incidents were not necessarily the focal points of the stories nor particularly explicit, two important facts that perhaps allowed their respective publishers to print the books without much fear of outcry or reprisal. The scenes of Thérèse and Isabelle are not viewed through the rose-tinted lens of someone like E. L. James. There are no cute euphemisms for body parts, no cutaways when the foreplay ends. It is, quite simply, an unfiltered exploration of the development of female desire and sexuality. They are young and subject to the universal follies of first love, but they are also beautifully, admirably unhinged in their passion, in their desire to please each other, in their desire to create a sort of haven from their oppressive surroundings.

Thérèse and Isabelle is not, however, merely erotic. Their relationship extends beyond their sexual experiences; their love is deeply felt and expressed. The narration is full of incredibly poignant and poetic reflections on the nature of attachment and obsession and an almost existential sense of self in relation to the world. And the greatest evidence of that might well be the last two lines in the book. I don’t want to give anything away, but I promise you’ll find it impossible not to react on a gut level.

Violette Leduc: A Complementary Reading List, by Sophie Lewis

Violette Leduc

L’Asphyxie, 1946 · L’affamée, 1948 · Ravages, 1955 · La vieille fille et le mort, 1958 · (Trésors à prendre, suivi de Les Boutons dorés, 1960) · La Bâtarde, 1964 · La Femme au petit renard, 1965 · Thérèse et Isabelle, 1966/2000 · La Folie en tête, 1970 · Le Taxi, 1971 · La Chasse à l’amour, 1973

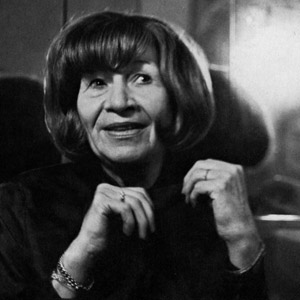

Simone de Beauvoir, mentor of Leduc and iconic feminist writer.

· The Second Sex (as required reading anyway), but particularly The Mandarins: a roman à clé, i.e. an insider’s guide to the intellectuals of her milieu.

Ann Quin, a feminist, ‘experimental’ author of 1960s Britain.

· Berg, a psychological thriller written as an internal monologue and Quin’s most critically acclaimed novel. The novel slipped out of print in the 1970s after Quin’s suicide and was reissued by Dalkey in 2001.

Katherine Mansfield

· The Garden Party and Other Stories, (1922) an impressionistic collection of short stories by modernist, lesbian writer Katherine Mansfield.

Marilyn Hacker, a highly acclaimed lesbian poet, critic and winner of a PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

· The trilogy of poetry collections Presentation Piece, Separations and Taking Notice

· Assumptions

Djuna Barnes, a modernist poet, playwright, journalist and visual artist. Writer Bertha Harris described her work as “practically the only available expression of lesbian culture we have in the modern western world” since Sappho.

· The Book of Repulsive Women

· Ryder

· Ladies Almanack

· Nightwood

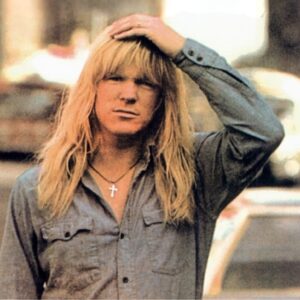

Jean Genet, a French writer, dramatist, and political activist. His art tackled LGBTQ themes and was controversial for its explicit portrayal of homosexuality and criminality.

· Our Lady of the Flowers

· The Miracle of the Rose

· The Thief’s Journal

· And the plays The Maids, The Balcony, Her

Marguerite Duras, a French novelist, playwright, and filmmaker whose work created stirs for its explicit depiction of sexuality.

· The Ravishing of Lol Stein

·Destroy, She Said

·The Man Sitting in the Corridor

Nathalie Sarraute, a French writer and lawyer whose experimental, psychological writing garnered her many honors.

· The plays Le Silence and Le Mensonge

· The autobiography Childhood

Lydie Salvayre, a feminist French writer who also practices psychiatry.

· The Power of Flies

· The Company of Ghosts

· La Méthode Mila

· Portrait de l’Ecrivain en Animal Domestique

Maurice Sachs, a gay French-Jewish writer.

· Witches’ Sabbath

Edmund White, a gay American novelist whose work draws on LGBTQ culture and history.

· The autobiographic trilogy A Boy’s Own Story, The Beautiful Room is Empty and The Farewell Symphony

· The non-fiction anthology The Burning Library

· His biographies of Jean Genet and others

Charles Baudelaire, a French poet, essayist, art critic, and translator of Edgar Allen Poe.

· The Painter of Modern Life

· Le Spleen de Paris (prose poems)

Leonora Carrington, British-born Mexican artist, surrealist painter, and novelist. A founding member of the Woman’s Liberation Movement in Mexico in the 1970s, her work examined female sexuality and the female role in the creative process.

· Down Below

· Self-Portrait (not a book but a painting)

Deborah Levy, a British playwright, novelist, and poet, whose work has been staged by the royal Shakespeare Company.

· Beautiful Mutants

· Black Vodka: Ten Stories

Sophie Lewis is a translator from French and Portuguese into English. She is also Senior Editor at And Other Stories press. Having spent the last five years in Rio de Janeiro, she now lives in London.

Tom Roberge

Tom Roberge is the Deputy Director at Albertine Books, and is the co-host—along with Open Letter's Chad Post—of the Three Percent Podcast.