Sen. Raphael G. Warnock Remembers How the Police Killing of Amadou Diallo Sparked His Activism

"It didn’t make much sense for us to be talking about justice in the classroom if we weren’t willing to get in the struggle in the streets."

In the early 1990s New York City was hot with racial tension, still bubbling over from a spate of racially motivated attacks and killings during the 1980s. When I arrived in the city, New Yorkers were still protesting the murder of Yusuf Hawkins, a sixteen-year-old Black teenager who was shot to death in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn on August 23, 1989.

Yusuf and three friends had gone there that evening to check out a used car, when they were accosted by a group of about thirty youths, all but one of whom were white and some of whom wielded baseball bats. During the attack, Yusuf was shot twice in the chest. According to media accounts, the attack was instigated by an eighteen-year-old, who was so angry about his ex-girlfriend telling him she was inviting her Black and brown friends to a party that he gathered youths from the neighborhood to attack them; the mob wrongly assumed Yusuf and his crew were the guests.

The ex-boyfriend told the police a somewhat different story—that his ex had threatened to send her Black male friends to beat him up and that is why he and his friends assumed Yusuf was there. One thing became clear: Yusuf was not connected to or aware of any of this. The murder of the unsuspecting teenager caused massive outrage, and crowds of mostly Black protesters, led by the Reverend Al Sharpton, marched through the insulated neighborhood to demand justice.

Many of its mostly white residents resented the protests, waved hateful signs, and used racial slurs to harass the protesters. But the marchers kept coming back, expressing anguish and demanding justice, as the cases of those arrested and charged wound their way through the courts.

Black men seemed in peril. They had been marginalized by society and targeted by police. Mass incarceration had begun to siphon scores of them from their communities.

There had been other racially motivated killings: Willie Turks, the thirty-four-year-old Black Metropolitan Transportation Authority worker who was pulled from a car by a white mob and beaten and stomped to death in 1982; Eleanor Bumpurs, a sixty-six-year-old, mentally disturbed Black woman, shot to death by police as they tried to evict her from her home in October 1984; and Michael Griffith, a twenty-three-year-old Black man who, along with his friend, was attacked by a white mob outside a pizza parlor and chased onto a highway, where he was fatally struck by a passing car in an area of Queens called Howard Beach in December 1986.

When Spike Lee’s movie Do the Right Thing hit the big screen in 1989—exploring the racial tension in a Brooklyn neighborhood, Bed-Stuy, between its African American residents and the Italian American owner of a local pizzeria and ending with the killing of an unarmed Black man by the police—this was art imitating life in its rawest form.

Black men seemed in peril. They had been marginalized by society and targeted by police. Mass incarceration had begun to siphon scores of them from their communities, so they were missing from their families. A generation of children was growing up fatherless, or visiting their daddies in jail, perhaps even presuming that life would land them there, too.

And then, in 1999, a police shooting would rock New York City.

On February 4 of that year four New York City police officers in plain clothes shot a Black man, a twenty-three-year-old Guinean immigrant named Amadou Diallo, at about 12:40 am in the vestibule of his own apartment building in the Bronx. The officers later said they mistook him for a serial rape suspect who had last struck about a year prior and thought he was going for a gun when he reached into his pocket. The officers fired forty-one shots, striking Diallo nineteen times. He had no weapon. He was trying to pull out his wallet.

Just a year and a half before that in August 1997, a thirty-year-old Haitian immigrant named Abner Louima had been arrested outside a Brooklyn nightclub and then taken to a police precinct, where he was brutally beaten and sodomized with a broken broomstick or the handle of a toilet plunger. The attack left injuries so severe that Louima needed multiple corrective surgeries. New Yorkers took to the streets, with demonstrators marching to city hall and the precinct where the torture had taken place.

Before the officers even went to trial in the Louima case, Diallo was shot. The shooting was like lighter fluid tossed into a burning flame. Once again, the city exploded. Outraged New Yorkers poured back into the city streets daily and, in recurring waves, made their way to 1 Police Plaza in downtown Manhattan, where they crossed a threshold that assured their arrests. And there were droves of arrests.

As I watched the protests, something inside me clicked this time. I knew I had to go. It wasn’t just that Diallo looked like me. But seeing his merciless killing, after all the other incidents, underscored the vulnerability of navigating the world in Black skin. He could have been me; I could have been him. He was just a hardworking young Black man, saving up money to go to college. I hurt for his heartbroken mother, who had watched her son travel to America with such hope. I hurt for his interrupted dreams and for my people whose skin alone made us such targets of hatred and violence.

Some of my seminary classmates were feeling the same. At least one of them, the Reverend Anthony Lee, now a Maryland-based pastor, was snatched and thrown against a gate by four plain clothes police officers who bolted from a rickety looking car and ran toward him one cold winter night as he was walking back to the seminary. Not knowing whether the men were officers or muggers, he decided that it was best not to run.

In a very tense moment, as they were frisking him, one officer yelled “gun” although he was unarmed. Seeing his life flash before him, he said, “I am a student at Union Theological Seminary. My ID is in my right front pocket.” After everything checked out, one officer advised, “Don’t act so nervous the next time.”

I’d brought my ministry to the streets, and there was no turning back.

Given what was happening around us and sometimes to us, it didn’t make much sense for us to be talking about justice in the classroom and singing about it in church if we weren’t willing to get in the struggle in the streets.

So I gathered up a small group, and we took the subway as close as we could and walked the rest of the way to the precinct. Throngs of others were already there, some with signs, calling for justice. As one group of protesters crossed the line of demarcation, were handcuffed, and were put in the back of a police van, the next group stepped up.

My group just flowed with the crowd, moving closer to the line and our eventual arrest. I’d never been arrested before, but I knew without a doubt that I was doing the right thing, that this was my time to get in the fight, to put my body in the game, to participate in the civil disobedience that I had heretofore just read about or witnessed from afar.

Finally, I was handcuffed and led to the back of a police van. Congressman Eliot Engel, who represented part of the Bronx, was in the van, as was the Reverend Michael Eric Dyson, who was teaching at the time at Columbia University. We were all transported to the precinct, processed, and released.

There was cautious hope in the community that the protests would push the then mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, past the arrogance he had displayed to citizens’ previous complaints about police brutality and racism and the need to address them. The police commissioner, Howard Safir, had not suspended the four officers involved, and in his one-year tenure Safir had shown little interest in addressing police brutality. A Bronx grand jury indicted the officers on charges of second-degree murder, but after an appeals judge ordered a change of venue to Albany, the state capital, because of “public clamor,” a jury of four Black and eight white jurors acquitted the officers of all charges on February 25, 2000.

And any hope that our outrage and protests might prompt meaningful change was further dashed when an internal New York Police Department investigation found that the officers did not merit any disciplinary action since they had not violated department guidelines.

The outcome was disheartening. But I was forever changed. I’d brought my ministry to the streets, and there was no turning back.

__________________________________

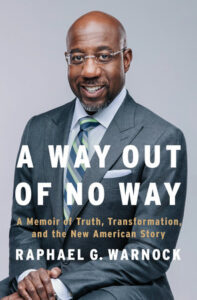

Excerpted from A Way Out of No Way by Raphael G. Warnock Copyright © 2022. Available from Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Raphael G. Warnock

Senator Reverend Raphael G. Warnock serves as the senior pastor of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church of Atlanta. He also has served at the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church of Birmingham, the Abyssinian Baptist Church of Harlem, and the Douglas Memorial Community Church of Baltimore. Senator Warnock holds degrees from Morehouse College and Union Theological Seminary. He is a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., a lifetime member of the NAACP, and the former chairman of the board of the New Georgia Project. He is the author of The Divided Mind of the Black Church and A Way Out of No Way. In January 2021, Warnock became Georgia’s first Black senator.