Selling Books from William Faulkner's First Writing Room

On a New Orleans Gem, Faulkner House Books

Before William Faulkner moved to Rowan Oak in Oxford, Mississippi to create Yoknapatawpha County, he rented a room in New Orleans’ French Quarter for six months, long enough to write his first novel, Soldiers’ Pay. He watched people on the street and dined with them—beggars and colonels, tourists and artists, drunks and longshoremen—and began writing about them, selling a series of “sketches” to The Times-Picayune and The Double Dealer to pay his rent. From experiences and characters he met here in 1925, Faulkner set his second novel, Mosquitoes, on Lake Pontchartrain, and returned to New Orleans as the setting for Pylon.

Faulkner’s experience in the little brick room at 624 Pirate’s Alley was formative. “The importance,” James G. Watson writes in Thinking of Home: William Faulkner’s Letters to His Mother and Father, 1918-1925, “can hardly be exaggerated.” New Orleans nurtured the artist who would write novels about “the human heart in conflict with itself.” As he said in his 1949 Nobel acceptance speech, only such problems of the human heart are “worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.” This city, so different from his Protestant country origins in north Mississippi, is where he sat by the Cabildo at Jackson Square and “pondered on the mutability of mankind.” In one sketch, “Mirrors of Chartres Street,” Faulkner marvels at the moon in the sky: “Even those who carved those strange flat-handed creatures on the Temple of Ramses must have dreamed of New Orleans at moonlight.”

Photo by Ashley Rouen.

Photo by Ashley Rouen.

Decades later, Joe DeSalvo and Rosemary James opened that room—where Billy Falkner first grew comfortable writing fiction and committed to adding the “u” to his name—to the public as an independent bookstore. Adding to the literary heritage of New Orleans, the DeSalvos, Kenneth Holditch and others, concurrently founded the nonprofit Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Society to assist writers and at-risk youth. The plaque on its facade leads with Faulkner and reveals the house was built in 1840 on grounds formerly occupied by a French colonial prison. (Although, as Rosemary points out, the date on the plaque is erroneous; the townhouse was actually built in 1837, according to public records, by Melassie LaBranche, who built several townhouses for herself and other planters who lived primarily upriver.)

“We couldn’t live in such an historic property without sharing it with other book lovers,” Rosemary says.

The DeSalvos acquired the property in 1988 and performed a two-year renovation, designing the ground floor as the bookstore and the three floors above as their private residence. As a corporate tax attorney, Joe had been maintaining his sanity with a daily dose of fiction and numerous rare book acquisitions. Rosemary was a journalist, interior designer, and marketing company owner. She shares credit with fellow reporters for breaking the story of DA Jim Garrison’s investigation into President Kennedy’s assassination and co-authored the nonfiction book Plot or Politics, based on this investigation, in 1967.

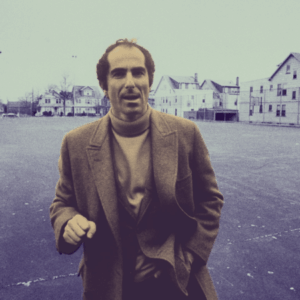

As the book collector and classicist of the couple, Joe manages the bookstore—located just a few miles downriver from his alma maters, Jesuit High School and Loyola University, where he was Valedictorian, Class of 1950. He still keeps business and tax records by hand on big green ledger paper and calls publishing house agents by their first names when making biweekly book orders. When loyal customers and book collectors around the country land a cache of rarities, they call and ask for Joe.

Joe DeSalvo sweeping Pirate’s Alley between Faulkner House Books and St. Anthony’s Garden & St. Louis Cathedral.

Joe DeSalvo sweeping Pirate’s Alley between Faulkner House Books and St. Anthony’s Garden & St. Louis Cathedral. Photo by Alex Johnson.

New Orleans knows Rosemary’s charming personality from years on local television. As pro bono CEO of the nonprofit Society, she runs its Words & Music Festival and William Faulkner-William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition. Each spring, thousands of submissions flood the store’s mailbox. Past winners include Stewart O’Nan, who wrote his 16th novel last year (just one behind Faulkner’s 17), Brett Lott, featured in Oprah’s Book Club, and Julia Glass, who would go on to win the National Book Award. The competition launches careers and gives emerging writers the resources to keep working on their art. When Maurice Carlos Ruffin won the novel-in-progress category in 2014, the recognition and prize money pushed the local short story writer to finish his debut novel. Ruffin’s winning entry was an earlier version of We Cast a Shadow, due out in 2019 from One World Random House.

“Rosemary and Joe are true supporters of literary art,” Ruffin says. “For decades, they’ve encouraged writers to submit [and join] a thriving international community. I owe a large part of my success to their selfless backing of my work.”

Rosemary also packs the Words & Music festival with author panels, editor and agent workshops, and cocktail entertainment at the Monteleone Hotel. While she emcees Words & Music and keeps its programming on schedule, Joe mans a pop-up book shop in an adjacent room, a satellite Faulkner House, with curated selections and book-signings with the internationally acclaimed judges and panelists.

The lineup at this year’s five-day “conference,” as Joe calls it, from December 6-10, promises to be a true celebration—it begins the day after he turns 85. Bestselling authors Reza Aslan and Walter Isaacson will be here. And it will serve as an informal “welcome home” for Isaacson, who recently announced his departure from leading the Aspen Institute to join Tulane’s faculty in his hometown of New Orleans. He’s also judging the nonfiction category of this year’s competition, and will be signing his latest biography, Leonardo da Vinci, to be released by Simon & Schuster in October.

*

Guidebooks feature Faulkner House Books on the must-visit lists and design magazines stage photo shoots in the residence, most recently in an Elle fashion spread. Both are venues for free literary events throughout the year. And the charm of the place was as evident to Faulkner as it is to contemporary visitors.

While living in the ground-floor room and sharing a bathroom with the eight-or-so other tenants, Faulkner, who had then published only a small book of poetry, The Marble Faun, lived with the painter William Spratling and wrote with Sherwood Anderson. Excited about Soldiers’ Pay, young Faulkner wrote in a letter to his mother, Mrs. Maude C. Falkner, postmarked April 23, 1925: “I have got a dog-gone good novel. Elizabeth and Sherwood both say so. Sherwood says he wishes he thought of it first. They have taken me in charge, wont [sic] even let me read anything until I finish it. . . . I hope to have it finished by the end of June.”

In another letter home, “Billy” describes the space that Joe and Rosemary eventually made a bookstore: “My room gives directly onto the alley beside the St Louis Catherdral [sic] garden. . . . This is the best part of town to live in, I think. Quiet and peaceful, and the grass and the trees in the cathedral garden just outside my door. And only about five minutes (walking) from Canal street [sic]. Isn’t it funny, how comfortable any place you call your own, is?”

Photo by Alex Johnson.

Photo by Alex Johnson.

When I worked at Faulkner House Books during law school, I saw tour groups pass by the wavy-glass window panes and heard their guides say Faulkner’s ghost haunts the place. Joe dismisses that, but remembers when Joan Williams visited and slept in their top-floor loft. She felt close to her once mentor and lover, claiming she smelled his pipe’s tobacco smoke. If anything really haunts the property, I’ve never sensed it, though when Criolla—Joe and Rosemary’s miniature chocolate poodle—has to go, her bark can border on sinister. But when Joe stands from his desk, Criolla’s silver Saint Frances medal jingles at the collar as she twirls and dances in circles; customers frequently “aww” and pet her on their way out the door.

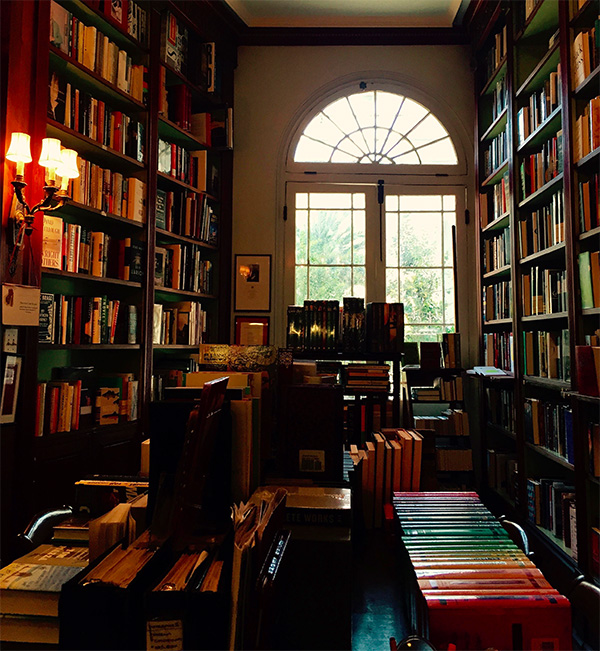

There are slow days in a French Quarter bookstore, but never boring ones. Too many ideas surround you stacked from the floor to ceiling. Joe doesn’t keep any running inventory log, so on one cold day with few visitors, I tried counting the books. I multiplied the number of spines—accounting for various widths—by the number of shelves. The total estimate was 7,525 books, and more than nine-tenths of his stock was literary fiction. Joe keeps a substantial poetry collection in two tall cases; several shelves of nonfiction, split among New Orleans-interest and literary biographies; and some playwriting and Greek and Roman classics; but literary fiction is the heart of Faulkner House. “I don’t have room for anything else,” he says. “I want people to come in here, close their eyes and reach for something and pull down a great work, a book that moves them, one they won’t forget.”

Most days, though, are busy and Joe often asks, “Have there been any interesting customers today?”

Photo by Ashley Rouen

Photo by Ashley Rouen

There have been plenty: Jessica Lange bought Luc Sante’s The Other Paris and we spoke briefly of the beauty of St-Germain-des-Pres before she rode away on her bicycle. John Barry, author of Rising Tide, stayed for at least two hours and not once removed his bike helmet. Bourbon Street dancers tend to arrive early in the first hour of opening. Bukowski hunters come late and stinking. A lobster fisherman with sleeve tattoos was on vacation from Maine with his wife; he bought an entire set of Raymond Chandler. Willie Morris was a close friend of Joe’s before his passing, and one of Morris’s Yazoo City stories had me so near tears that I didn’t notice the family of tourists taking pictures until their laughter startled me out of my spell. Embarrassed, I stood up from the leather-topped partner desk so they could photograph the pristine sanctuary without a sentimental bookseller in view. Jamie Lee Curtis buys the books recommended by former actress, Joanne Sealy, who has worked at Faulkner House five-days-a-week since before Hurricane Katrina. When John Lahr is in town, he asks for Joanne, too. I didn’t recognize Roy Blount, Jr. from the length of his beard the first time I saw him enter the store, but once he started talking to Joe I recognized his Georgia drawl from NPR.

A serious book collector visited the store from Texas saying he’d come to New Orleans to gamble and find books. I showed him the 18th century French armoire enclosing rare Faulkner editions and quickly grabbed Joe from his office. Criolla did not move from her pillow. For an hour, the collector flipped the delicate, only slightly faded, not dog-eared, pages of a $10,000 first edition, first printing, Gone With the Wind. Then, abruptly, he shut the book, scanned the immaculate dust jacket one last time and declared he’d return after Harrah’s. Around closing time, the gambler entered sucking air and soaked from the evening storm. He did not say much, but asked to buy a less rare, but signed, Jazz first edition by Toni Morrison.

The point is, whether you’re in New Orleans to gamble and drink or write “a dog-gone good novel” like young Faulkner, you’ll find sanctuary at 624 Pirate’s Alley. The DeSalvos welcome you to Faulkner House Books.

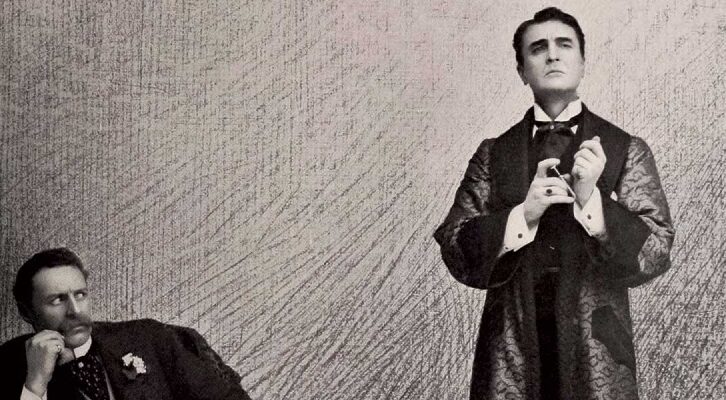

Feature photo via US Anywhere.

Alex Johnson

Alex B. Johnson grew up on a farm outside Royston, Georgia and studied history and international affairs at the University of Georgia. Alex lived in Washington, DC, and worked on Capitol Hill before moving to New Orleans to study law at Tulane and work at Faulkner House Books. The Bitter Southerner, OffBeat, and American Songwriter, among others, have featured his writing. Alex lives with his wife, Caroline, and dog, Mud, in New Orleans.