10 Magical Feminist Books to Inspire Creative Resistance

A Literature of Defamiliarization, Supernaturalization, and Border Transgressions

Writing magical realism can be risky; it’s easy to fall into clichés. But it should never be dismissed as some kitschy literary device. Its history and traditions are firmly rooted in the literature of resistance, in the literature of re-visioning. Which makes sense: If we don’t like reality as it is, with all its violence and injustice, we have to reimagine it. And sometimes, that reimagining includes leaps of enchantment.

The supernatural elements in magical realism can serve to disrupt reality, giving voice to the other. Patricia Hart first used the term “magical feminism” thirty years ago to describe the work of Isabel Allende, the Chilean-American author who was compared to Gabriel Garcia Marquez until critics turned cobalt blue. But Allende had her own literary vision. In magical feminism, the merging of the rational and the fabulist often includes strategies of defamiliarization, supernaturalization, and border transgressions, depicting witches and faith healers, shape-shifters and mixed-race protagonists, intersex and trans characters, and visions of femme-centric utopias.

Below, I’ve selected ten magical feminist books to embolden the spirit and inspire creative resistance.

The Stories of Eva Luna, Isabel Allende (Atheneum, 1991)

Allende is famous for writing hybrids of family history and fiction, giving voice to ghosts and sexually empowered women alike. In The Stories of Eva Luna, we meet characters on the brink of moments of social change—often with one foot in the old, oppressive world and one foot in a world they’re only daring to imagine. “She went by the name of Belisa Crepusculario,” Allende writes of one character, “not because she’d been born with it or baptized it, but because she herself had searched until she found the poetry of ‘beauty’ and ‘twilight’ and cloaked herself in it. She made her living selling words.” Magical feminism allows characters to create their own identities.

The Vicious Red Relic, Love, Anna Joy Springer (Jaded Ibis Press, 2011)

In her “fabulist memoir,” Springer uses text and image, re-imagined myth, deep sexual desire, and an imaginary friend made of tin foil to lead readers into a world where interpersonal ethics supersede tired, patriarchal social norms and death has no dominion.

Voodoo Dreams, Jewell Parker Rhodes (Picador, 1993)

Marie Laveau was born a free woman of color just before the Louisana Purchase made New Orleans—along with pretty much the entire Midwest—part of the United States. Laveau was barred from holding public office because of her race and gender, but by all accounts it was she, and not municipal authorities, who reigned over the city for the better part of the century. Although her influence—political, social, and spiritual—was legendary, the historical material on Labeau remains fragmentary. Enter the magical fiction of Jewell Parker Rhodes. Moving through the centuries, blending fact and vision, Rhodes brings the woman who walked like a queen vividly back to life, and makes her relevant to the here and now.

Watercolor Women Opaque Men, Ana Castillo (Curbstone, 2005)

Castillo is perhaps the most versatile of the magical feminists, equally at ease in poetry and prose. This epic in verse shows off Castillo’s sheer range, following Ella, a Chicana everywoman and single mother who describes herself as “Part Medusa/Part Mother Goose/and part Xochiquetzal” as she works, struggles, and busts through walls to raise her son, striving for more than the opaque version of masculinity that the world seems to require. Castillo imagines a utopia where:

They live for the fiestas,

Grind corn bare-breasted,

Let gay sons wear dresses,

Everyone has a job and a place

and the women

run it.

Sassafrass, Cypress, and Indigo, Ntozake Shange (St. Martin’s Press, 1982)

Sassafrass, Cypress, and Indigo came to me in the early ’90s, when I was stuck in the seemingly endless end-phase of a violent relationship, still bound to my ex because we’d had a child together, and here was a book that directly addressed domestic violence. The story follows three powerful, creative sisters as they begin to make their way in a world that is terrified of power and creativity in black women. Shange’s young, marginalized characters turn to each other more often than they turn to law enforcement, casting spells of protection and aspiring, always, to control their own fates.

The Legacy of Lucy Little Bear, Barbara Robidoux, (Blue Hand Books, 2017)

This novella’s poetically shifting point of view illuminates the experiences of shape-shifting women and marginalized men as they navigate threats, both from within their own families and communities and from the outside world, where indigenous women vanish and search parties are rarely formed.

Sexing the Cherry by Jeanette Winterson (Bloomsbury, 1989)

In a fantastic world that is and is not seventeenth-century London, Dog Woman, a giant murderer of Puritans who wears a skirt big enough to serve as a ship’s sale, finds a baby in the river and nurtures him until he’s ready to travel the world and his own strange mind. I mean, what could go wrong? Throw in the refracted fairytale of “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” and it’s enough to destabilize five centuries of patriarchal power structures. Historical magical realism at its gender queerest, this is a tale worth reading at least once a decade.

Nobody, Threasa Meads (Rare Bird Books, 2016)

Nobody, Threasa Meads (Rare Bird Books, 2016)

It might be a stretch to call Nobody a magical realist tale. However, I’d argue that it takes a kind of shape-shifting to transform from an abused girl with no control in her family into powerful author who can tell her story any damn way she chooses. In Nobody, Meads uses the second person and a choose-your-own-adventure format to disrupt the traumatic reality of her stepfather’s exploitation. As with classic choose-your-own-adventure books, it slowly becomes clear that choice is an illusion, but magic arrives in the act of re-narrativizing the experience, giving the adult author the agency she never had as a child.

Tracks, Louise Erdrich (Henry Holt, 1988)

Tracks, Louise Erdrich (Henry Holt, 1988)

Set in the early twentieth century, Tracks shows an entire North Dakota Anishinabe community standing on the brink of devastation from plague, tuberculosis, and forced relocation. As supernatural events come into play—from omens to revenge-induced tornados to apparitions of Jesus—the novel’s two narrators offer different interpretations. The mixed-race narrator Pauline sees things form an increasingly assimilated worldview as she finds herself trapped between her white and native identities, choosing, ultimately, to “ghost” herself into the white world—and paying a huge psychological price. The alternate narrator, an elder tribal leader, understands what’s at play through a traditional lens and demonstrates, ultimately, that it takes the spirit of the trickster, not the assimilationist, to survive and build new life from the ashes.

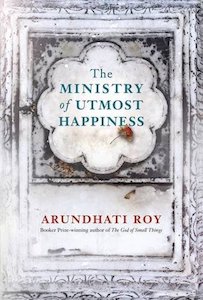

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, Arundhati Roy, (Knopf, 2017)

I read the God of Small Things in 1997 and have—along with the rest of the world—been waiting 20 years for another novel from Roy, a wildly prolific nonfiction author and activist. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is worth the wait. A fierce exploration of gender and political history, the novel transgresses the limits of traditional plot structure. Roy mosaics her characters’ separate lives and a fragmented post-colonial geography together, answering, ultimately, the lonely question on the back cover of the book: “How to tell a shattered story? By slowly becoming everybody. No. By slowly becoming everything.”

__________________________________

Ariel Gore’s most recent novel, We Were Witches, is out now.

Feature image: Moses, 1945 by Frida Kahlo