Seeking Stillness and Sunlight: On the Art of Fly-Fishing

David Coggins Makes a Case for the Angler's Lifestyle

Moving water thrills me. I can’t drive over a bridge without looking down at the river and wondering whether trout live there. I speculate about where they might be hiding and how I’d try to catch them. Then I break from my reverie before I swerve into oncoming traffic. If I’ve decided the river’s promising, I privately plot a return. It’s like discovering a secret hidden in plain sight.

The discovery is bittersweet, however, because the chances of coming back are low. Life interferes with the best angling intentions. I’ve studied maps with snaking blue lines and evocative names waiting to be fished: the Jefferson, the Test, the Spey, the Alta. There’s so much water, and it takes years, longer, to learn a river’s nature. The names of rivers I’ve yet to fish are etched in my head like the titles of great novels sitting unread on the shelf. I’m still trying to understand the rivers in my life beyond the most basic familiarity. Beneath the surface are mysteries we can barely make out, so we study and speculate and remember every detail we can. This is fishing.

By fishing, I mean fly fishing, with its traditional way of casting, wading or from a drift boat, often for trout. But also salmon, bonefish, striped bass, and more, all over the world. The obsession, when it takes hold, is global and total. A friend has an insight—Everybody knows about the salmon fishing in Iceland, but did you hear about their brown trout?—apparently it’s great, and I find myself on an esoteric website at midnight in a language I don’t read.

Angling is about anticipation and planning trips far in the future, but it also has a storied history. This sport has been practiced since Izaak Walton’s Compleat Angler was published in 1653, in ways that are, to the naked eye, fairly unchanged today, like a Shakespeare play performed on a thrust stage. Some people justify fly fishing with claims that it’s poetic, and, yes, there are moments of pure poetry, but the pleasures of fishing are also tactile and immediate. The theoretical considerations tend to enter my mind, sometimes against my will, when I’m not catching anything.

When upstanding yet angling-agnostic citizens find out I’m fishing for a week in Montana, they raise an eyebrow; when they find out I’m going to the Bahamas, they raise two. It’s as if I’m not merely leaving town but leaving society, the society that’s employed, productive, efficient, and to their mind, necessary. Fishing in the modern world, I’ve come to realize, is a contrary act. While it might improve one’s moral character (a possibly dubious theory), to fish with purpose and intensity, to seek sporting opportunities in far-flung places, strikes many as decadent.

Some people justify fly fishing with claims that it’s poetic, and, yes, there are moments of pure poetry, but the pleasures of fishing are also tactile and immediate.

Perhaps fishing is decadent, but it didn’t always seem that way. I began fishing as a boy not because I thought it was morally redeeming, but because I loved it. If anything, it felt natural. We had a cabin on a lake in Wisconsin, and what could make more sense than to row a boat out into the bay and cast to bass as the sun went down over the trees? What I enjoyed then I still enjoy now: the solitude and mystery, the bursts of action, the near misses, the occasional triumphs and, when it’s over, rowing home in silence, the water smooth as glass.

As a man, standing in a stream on a weekday afternoon in late spring, casting to trout, is a more conscious decision. I still do it for the sheer joy of being outside, of concentrating, of the doubts and rewards of being connected to a fish, of landing and releasing it. Fishing offers an internal reward, and that personal satisfaction is enough. This is the same reason why a good lunch—a proper three-hour lunch, where wine is ordered by the bottle not the glass—is so rare and rewarding. This escape is not exactly illicit, but it certainly takes you outside the course of events of the day.

Fishing is waiting. When I’m on the water, I’m out of time and the world recedes. Even when nothing seems to be happening, something is happening. The seeming nothing is what gives shape to the eruption of activity, it offers a symmetry, though really an asymmetry, to the strike. Tom McGuane wrote that it’s the long stretches of silence that give fishing its purpose. When Countess Almaviva sings her aria at the end of The Marriage of Figaro, it’s one of the most beautiful passages in music. You can listen to it anytime, but if you watch the opera at the Met it’s four hours into the production. Getting to that point reveals the burden of her character’s loss and the delicate forgiveness of her husband. All that time is necessary to feel the full weight of what she’s singing. Similarly, catching a fish without waiting is a distorted experience. You can’t live on dessert alone.

And yet even waiting on the water I’m more engaged than I am anywhere else. An angler is sensitive to changes in the weather, to shade and sun, to any movement on the stream. There are clues everywhere lightly hidden: which insects are appearing that a trout might eat, the speed of the current, shadows faintly moving under the water. When this knowledge converges with enough skill and conspires with luck, I might catch a fish.

Fishing is waiting. Even when nothing seems to be happening, something is happening.

But more often I don’t catch a fish. That’s why fishing requires coming to terms with the fact that you can do everything exactly the way you want to and still fail. Are you comfortable with that? I hope so. Fishing measures success in an invisible way. Most fly fishing is catch and release, by rule or by principle. At the end of the day, there’s nothing to show for it. Catching a fish first exists in the moment and then in the memory, like childhood, with photos that don’t do the experience justice.

When people ask me about the attraction to fishing, which they often do because they genuinely want to know or are mildly exasperated that I do it, I tell them that it’s an outdoor sport. This is obvious of course, but it’s the basic truth. You’re in the natural world, usually in a beautiful place. I read once that if you stand all day on a typical east-west street in Manhattan, like the one I live on, you’ll receive eight minutes of direct sunlight. I don’t know if that’s true, but it certainly feels true. When I go fishing, I know I’ll be outside for the next eight hours with as much direct sunlight as I want.

There are the angling specifics, the rituals and peripheral pleasures that are also part of the sport. Early breakfast at a saloon before driving into Yellowstone National Park, hash browns well done. Buying ice at the gas station, picking up lunch. Talking to the slightly dismissive men at the local fly shop and trying to sort out their cryptic advice about what’s been working. They possess the superior air of harboring secret knowledge that record store clerks used to have. The curious glances at the trucks driven by guides hauling drift boats—and guides always drive trucks, usually with a crack snaking across the windshield.

There are codes which exist in any intense pursuit. There are outright snobs, reverse snobs, and people so isolated they can’t be considered either. There are those who embrace the new, wear highly technical clothes and endorse the latest technology. There are anglers who are so passionately behind the times they wear waxed canvas, which is heavy, hot, and doesn’t even keep the water out when it really needs to; they do this as a point of tradition and pride. There are the bamboo anglers who track down and then spend a small fortune for a rod made by one specific builder who’s usually dead. The bamboo rod becomes like a suit of clothes that’s so nice you can’t wear it—the rod is too valuable to actually fish with. Yes, members of these irrational subgenres are part of the angling world as well. Sometimes, in polite society, we recognize one another.

That’s why anglers are like spies. We keep our motives to ourselves, the details and schemes can’t be shared with anybody who’s not a fellow traveler in this world of secret obsession. Some of this is social convenience, to keep from boring civilians who are disinterested, incredulous, or downright opposed. In my family of angling agnostics, there’s a highly enforced one-minute rule on fishing stories. Anything longer leads to relatives with unfocused eyes settling in the middle distance. I admit my fishing desire can be so intense I don’t like to describe it to the unafflicted. I don’t want other people to know, and perhaps I don’t want to admit to myself, just how much I think about fishing. There’s something slightly suspicious about this devotion, like a weakness for absinthe, an eccentric habit that should be tempered before it turns into a depraved addiction. Too much fishing—and too much absinthe for that matter—can leave you with an overgrown beard, far from home, raving about the fate of the world. It’s like I’m part of a disreputable cult known to have suspect views about the creation of the universe. But now I’m a true believer.

There’s something slightly suspicious about this devotion, an eccentric habit that should be tempered before it turns into a depraved addiction.

There’s a spring creek not far from Livingston. It’s late summer. I pull off the paved road and drive slowly through fields, waiting for the cows to move out of the way. I park and open a beer. This is in Montana, and you can’t buy beer in a grocery store on Sundays before 9 am, which is a lesson you only need to learn once, and now I buy it the night before.

This time of preparation—assembling the rod, pulling on waders, lacing up boots, tying on flies—is one of my favorite parts of fishing. Angling is more than being on the water—it’s the entire day, the anticipation, the fishing of course, the stories afterward, the remembering and then the misremembering. The same way that going to lunch at Le Grand Véfour means walking through the Palais Royal and wondering what you’re going to order. I take my time; the angling day is still full of possibility, and I can’t help envisioning potential triumphs while ignoring the more likely small, morale-fraying setbacks that are intrinsic to the sport.

One thing that always surprises me whenever I arrive at streams is how harmless they feel, innocent of my intentions. Tall grasses and low willow trees blow sleepily along the bank. It’s just another day, with only slight variations of countless other days here. What’s different is that on this day I’m here, I want to intersect with everything that’s unfolding on its own. The seeming sense of peace on the water gives way, under observation, to furious activity that’s nearly invisible to those not attuned to it.

Looking closely reveals signs of life, trout coming up and feeding near the surface. Tactically, that means fishing a dry fly—one that floats—which remains the platonic ideal of the sport. If all goes well, you see the fish break the water and take your fly, an eternal thrill. This makes me excited and a little nervous, now I have to make decisions. The fish are doing their part, I have to do mine. I choose a Royal Trude, rust and white, and then tie on something to a line behind it, a smaller dry fly, a little blue-winged olive, the size of a used pencil eraser, to float a few feet after it. Presumably this gives me more chances, or at least allows me the illusion that I’m being scientific.

My first cast is a bad cast. It’s too short and not even straight. This is a tradition of mine. I don’t start well. Have you met somebody you find attractive and made a witty remark to them right out of the gate? Well then congratulations, perhaps you of iron nerves and sharp presence of mind can come catch this trout. I, however, need to warm up.

The drift is the goal. The drift is everything. When the fly floats seamlessly in the current over a feeding fish, the anticipation is real. I’m waiting, praying, it will come up and take the fly. These moments when the fly passes above the head of a trout are wonderful and excruciating. This is the same rush of excitement gamblers feel when they scratch off a lottery ticket. They don’t really think they’re going to win—they know better—it’s the chance of winning they’re addicted to. That’s the same when you fish. The possibility keeps you making one more cast.

During the drift, one second, two, three, an interminable four seconds, anything is possible. Then suddenly it’s not at all possible. The fly was rejected, ignored. Was it the drift, was it the fly? The fish are still out there, they’re still feeding. But not on my Royal Trude, not on my blue-winged olive. The water is clear—they definitely saw it. They just didn’t like it. I take stock, get technical and tie on an emerger pattern. This imitates an insect evolving from a larva to an adult; it sits in the film of water and is harder to see. I take my time, which is difficult when the fish are feeding right in front of me.

I make the cast where I want to, a small triumph, and the fly floats over the trout’s head. Or at least where it was a few seconds ago. Then: a minor hiccup in the surface, like a small pebble fell into the water. The trout. No matter how many times this happens the action still feels abrupt. The fish took the fly, but until I raise my rod it’s impossible to know if the trout’s hooked. When the line tightens and I feel the pressure, that steady weight, a sideways movement of its head, only then do I know for sure. That’s the vital moment. The fish is on.

This state of affairs seems to extend endlessly—though it’s only about a second—then the trout heads away from me—and quickly. I want to see that fish, I want to know what I’m dealing with. So many things can go wrong if it jumps from the water, it might throw out the hook. But it can also break the fine line if I pull it too insistently. If it swims too far downstream it might keep going and break off that way. I know all this because I’ve lost fish almost every way imaginable, especially on this stream, and they all hurt differently. All happy fish stories are alike. Each unhappy one is unhappy in its own way.

With steady pressure on the line I finally bring the fish near the bank. I raise the rod even farther and slide the fish over my net. This is also delicate, because a trout usually makes one last dash, and when it’s this close, it’s a very unpleasant time to come up short. But this time it works. It all works. The fish is lovely, a long, healthy cutthroat trout, gold and deep pink, its eye black and unblinking in the shallow water. I don’t need a photo. I revive it, and once it feels like itself it swims back down to the bottom of the pool.

The drama’s over in two minutes, maybe three. When everything succeeds, it seems inevitable, even easy in a way. How else was it supposed to happen? Well, there are so many ways to be heartbroken on the water that sometimes the joy comes from merely avoiding mistakes or bad luck. Catching a fish brings the simple satisfaction and absolute fact of everything unfolding as planned. The presentation of a fly, managing the drift, the physical action of fighting a fish and successfully landing it. This never feels like I’m taming nature, more like being in alignment, and understanding it better, at least for a short time. Fishing is a search for the fleeting connection to something alive that can never be fully known. Once the fish is gone, it’s just me on the bank. There are mountains in the distance. Nobody knows where I am. Sometimes you get lucky.

__________________________________

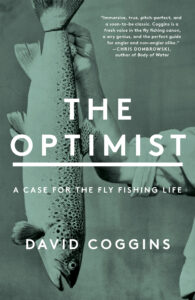

Excerpted from The Optimist by David Coggins. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by David Coggins.

David Coggins

David Coggins is the author of Men and Manners and the New York Times bestseller Men and Style. He writes about fly fishing for Robb Report and tailoring, drinking, and travel for numerous publications, including the Financial Times, Bloomberg Pursuits, and Condé Nast Traveler. Coggins lives in New York and fishes regularly in the Catskills, Wisconsin, and Montana.