Seeking a Counterculture of Commitment in an Age of Infinite Browsing

Pete Davis on Making Meaning Through the Radical Act of Limiting Your Options

Infinite Browsing Mode

You’ve probably had this experience: It’s late at night and you start browsing Netflix, looking for something to watch. You scroll through different titles, you watch a couple of trailers, you even read a few reviews—but you just can’t commit to watching any given movie. Suddenly it’s been thirty minutes and you’re still stuck in Infinite Browsing Mode, so you just give up. You’re too tired to watch anything now, so you cut your losses and fall asleep.

I’ve come to believe that this is the defining characteristic of my generation: keeping our options open.

The Polish philosopher Zygmunt Bauman has a great phrase for what I’m talking about: liquid modernity. We never want to commit to any one identity or place or community, Bauman explains, so we remain like liquid, in a state that can adapt to fit any future shape. And it’s not just us—the world around us remains like liquid, too. We can’t rely on any job or role, idea or cause, group or institution to stick around in the same form for long—and they can’t rely on us to do so, either. That’s liquid modernity: It’s Infinite Browsing Mode, but for everything in our lives.

For many people I know, leaving home and heading out into the world was a lot like entering a long hallway. We walked out of the room in which we grew up and into this world with hundreds of different doors to infinitely browse. And I’ve seen all the good that can come from having so many new options. I’ve seen the joy a person feels when they find a “room” more fitting for their authentic self. I’ve seen big decisions become less painful, because you can always quit, you can always move, you can always break up, and the hallway will always be there. And mostly I’ve seen the fun my friends have had browsing all the different rooms, experiencing more novelty than any generation in history has ever experienced.

But over time, I started seeing the downsides of having so many open doors. Nobody wants to be stuck behind a locked door—but nobody wants to live in a hallway, either. It’s great to have options when you lose interest in something, but I’ve learned that the more times I jump from option to option, the less satisfied I am with any given option. And lately, the experiences I crave are less the rushes of novelty and more those perfect Tuesday nights when you eat dinner with the friends who you have known for a long time—the friends you have made a commitment to, the friends who will not quit you because they found someone better.

The Counterculture of Commitment

As I have grown older, I have become more and more inspired by the people who have clicked out of Infinite Browsing Mode—the people who’ve chosen a new room, left the hallway, shut the door behind them, and settled in.

It’s the television pioneer Fred Rogers recording 895 episodes of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood because he was dedicated to advancing a more humane model of children’s television. It’s the Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day sitting with the same outcast folks night after night because it was important that someone was committed to them. It’s Martin Luther King Jr.—and not just the Martin Luther King Jr. who confronted the fire hoses in 1963 but also the Martin Luther King Jr. who hosted his thousandth tedious planning meeting in 1967.

As this new type of hero captured my admiration, I started appreciating a different constellation of figures from my childhood than I did at the end of my teenage years. The “cool teachers” faded in my memory—I can’t even remember some of their names—but the slow-and-steady ones have lingered.

There was the intimidating stage crew and robotics director from my high school, Mr. Ballou, who built up a student cult of misfit tinkerers and future engineers. He seemed to have a whole wing of the school to himself filled with half-built projects, technology from various decades, and devoted student acolytes clad in matching black T-shirts. Most of the school, myself included, were a bit afraid of him—scared we would get in his way, or worse, break something. But that was the key to his method. If you were willing to face your fears and engage with him, he would train you in any one of the dozens of craft skills he knew.

Over time, I started seeing the downsides of having so many open doors. Nobody wants to be stuck behind a locked door—but nobody wants to live in a hallway, either.

One time, I made a funny video with my friends for a school variety show. He saw it and told me that I had “absolutely no sense of framing”—and that the video wasn’t good enough yet to show to a crowd. My other teachers, just delighted that a student was making something, had always heaped praise on my teenage filmmaking. Mr. Ballou was different. He insisted that if you were going to get into a craft, you should hone it. I remember complaining that he was being a little hard on me.

But the Ballou method cut both ways. Another time, I had the idea of building a concert venue inside the school’s junior courtyard. Every teacher thought the idea was ridiculous—What the heck are you even talking about? But when I told Mr. Ballou, he wasn’t taken aback at all. If I learned the engineering software AutoCAD and designed a blueprint, he told me, he would help me advocate for building it. That’s a real teacher—demanding more of you but committing to you if you commit to learning.

I took piano lessons from Mrs. Gatley, who clocked four decades in the same chair next to the same grand piano in her living room on Oak Street. While my other friends got to bop in and out of lessons, one or two years at a time, and learn whichever songs they wanted (Vanessa Carlton’s “A Thousand Miles” and Coldplay’s “Clocks” were my era’s songs), Mrs. Gatley was old school. It wasn’t just that her students had to learn their scales and play classical music. By taking lessons with Mrs. Gatley, you were signing up to join an entire immersive experience that was bigger than piano—and bigger than you.

Just taking weekly lessons wasn’t allowed—you had to follow the full Gatley calendar with all her other students. There was the fall recital and the Christmas concert, the sonatina festival and the June recital—and each of these events had a corresponding gathering preceding them where every student would prepare together. You had to learn the history of the pianoforte, the difference between the Baroque and the Romantic periods, and the proper way to bow after finishing playing.

You also couldn’t really quit. Once, in middle school, I asked Mrs. Gatley if I could take a year off.

“You can, I guess,” she responded, “but we don’t really take a year off here.”

I ended up spending twelve years in the Gatleyverse. As a result, I learned about a lot more than just piano in Mrs. Gatley’s living room. I saw what it was like to watch older students play some impossible song—and eventually learn to play it myself. Because Mrs. Gatley knew me for so long, she had the insight and authority to give deeper advice than other teachers, like when she told me: “You move a little fast in life; you might feel better if you slowed down.” And when my dad died, it meant something that Mrs. Gatley—who knew him from all the concerts over the years—came to the funeral. You couldn’t get that from some one-off teacher who let you play “A Thousand Miles” during the first lesson and quit the first time you got bored.

Folks such as Mrs. Gatley and Mr. Ballou—and icons like Dorothy Day, Fred Rogers, and Martin Luther King Jr.—aren’t just a random assortment of people. I’ve come to think about them as part of a shared counterculture—a Counterculture of Commitment. All of them took the same radical act of making commitments to particular things—to particular places and communities, to particular causes and crafts, and to particular institutions and people.

The heroes of the Counterculture of Commitment—through day-in, day-out, year-in, year-out work—become the dramatic events themselves.

I say “counterculture” because this is not what today’s dominant culture pushes us to do. The dominant culture pushes us to build our résumés and not get tied down to a place. It pushes us to value abstract skills that can be applied anywhere, rather than craft skills that might help us do only one thing well. It tells us to not get too sentimental about anything. It’s better, this culture tells us, to stay distant—just in case that thing is sold off or bought out, downsized, or made “more efficient.” It tells us to not hold true to anything too seriously—and to not be surprised when others don’t, either. Above all, it tells us to keep our options open.

The kinds of people I’m talking about here are rebels. They live their lives in defiance of this dominant culture.

They’re citizens—they feel responsible for what happens to society. They’re patriots—they love the places where they live and the neighbors who populate those places.

They’re builders—they turn ideas into reality over the long haul.

They’re stewards—they keep watch over institutions and communities.

They’re artisans—they take pride in their craft.

And they’re companions—they give time to people.

They build relationships with particular things. And they show their love for those relationships by working at them for a long time—by closing doors and forgoing options for their sake.

When Hollywood tells tales of courage, they usually take the form of “slaying the dragon”—there’s a bad guy and a big moment where a brave knight makes a definitive decision to risk everything to win some victory for the people. It’s the man standing in front of the tank, or the troops storming up the hill, or the candidate giving the perfect speech at the perfect time.

But what I’ve learned from these long-haul heroes is that this isn’t the only valor around. It’s not even the most important type of heroism for us to model, because most of us don’t have to face many dramatic, decisive moments in our lives—at least not ones that spring up out of nowhere. Most of us just confront daily life: normal morning after normal morning, where we can decide to start working on something or keep working at something—or not. That’s what life tends to give us: not big, brave moments, but a stream of little, ordinary ones out of which we must make our own meaning.

The heroes of the Counterculture of Commitment—through day-in, day-out, year-in, year-out work—become the dramatic events themselves. The dragons that stand in their way are the everyday boredom and distraction and uncertainty that threaten sustained commitment. And their big moments look a lot less like sword-waving and a lot more like gardening.

_____________________________________________

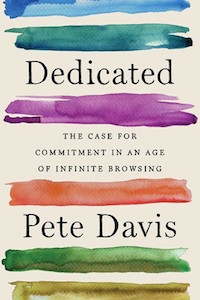

Excerpted from Dedicated: The Case for Commitment in an Age of Infinite Browsing, by Pete Davis. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Pete Davis.

Pete Davis

Pete Davis is a civic advocate from Falls Church, Virginia. He works on projects aimed at deepening American democracy and solidarity. Pete is the cofounder of the Democracy Policy Network, a state policy organization focused on raising up ideas that deepen democracy. In 2015, he cofounded Getaway, a company that provides simple, unplugged escapes to tiny cabins outside of major cities. His Harvard Law School graduation speech, “A Counterculture of Commitment,” has been viewed more than 30 million times.