1.

At thirteen, I found myself living in the middle of the marshlands. Legend has it that the slow-moving water once held hundreds of hippos. The sun bounced off their eyes and ears and nostrils as they waited for dusk, for their time to hunt among the rushes and reeds and shrubs at the water’s edge. The invaders who settled several miles north, in Londonshire, drove these creatures out of their territory and into extinction. But another legend has it that the hippos survived, that they still lived in the upper south and only showed themselves during the supermoons. Hippoland, the town I lived in and that lay nestled between Westville and Londonshire, was named after them.

In Westville, government ministers zoomed about in Mercedes-Benz sedans, oblivious of the potholes on most of the road snaking in and out of Westville International Airport from where they frequently emerged, clad in oversized suits and bearing black suitcases, suitcases now empty of their contents, the contents now safely deposited in Swiss banks.

In Londonshire dwelt the remnants of the former colonial rulers of Victoriana. They built big houses, fenced them in with willow whips, smoked a variety of intoxicants, swaggered about in cravats and kept their Luger pistols close in order to contain the restive natives on whose land they had built their homes.

In the East African nation of Victoriana, the monsoon winds from the Indian Ocean that marked the beginning of the rainy season always arrived with a whisper. They began by sweeping over Westville, picking up the trash thrown out of the high-rise buildings and spreading it all over the valley, and forcing vehicles off the road. Then they moved on to the southern slopes, on the outskirts, then turned north, past the tea plantations and corn fields and blew the dust from the desert plains onto the potato fields, hurled away the fertilizer, sometimes even the wheat and barley and oats, and spread the pollen everywhere so that everywhere there grew spruces and figs and mugumo and pear trees.

Those who toiled in Londonshire and Westville all hailed from Hippoland. They sold their labour cheap, like the hundreds of Indian men before them, who had arrived in ships and dhows and built with their bare hands the railway lines criss-crossing Victoriana. Some of those workers managed to survive the heat strokes and the wild game and chose to settle in Hippoland, waiting for the largesse they had been promised to finally trickle down to them. They began to sell mahamris and hippo tusks and skins and, of course, spices which went on to change our tastes forever. They married the locals and built dress shops, bicycle shops, dairy shops, kerosene shops and market stalls and temples and churches and bars and, in time, became well and truly part of Hippoland.

When the workers came back home, they carried with them stories to be shared at the Sunday football games or at Mexico 86.

Mexico 86 was a beer hall, a simmering pot in which stories from Westville and Londonshire were stewed, strained, mixed and served up to neighbours, friends and foes, especially after the sun had slowly set behind the hills (it was also a shelter from the cold and the rain). Mexico 86 was always dimly lit, with cigarette smoke looping around the shapes huddled at the wooden tables, over overflowing ashtrays and beer bottles and leftover chicken, over servings of Miti wine made from water and sugar cane and organic honey, fermented in wooden drums and served in calabashes and cow horns.

Whenever Westville banned a book, someone would smuggle a copy into Mexico 86. And that is how Mexico 86 became the fount of stories, factual or fictional or both.

My Aunt Sara was quite the storyteller. I did not know this when I met her. I did not even know I had an aunt by that name until my father told me that her place was going to be our place of exile.

Exile, for my brother Mito and me.

2.

My life had been ordinary. Until five days ago when a friend handed me a cigarette. We were standing by the abandoned tennis courts, right beside the Westville Convent School gym, behind the purple bougainvillea that spread over the small conifer shrubs. The perfect cover. There were never any tennis matches. Someone said that the money donated by the Church of the Most Holy to build the courts had been siphoned off by a board member from the Ministry of Religion in Westville. We were unconcerned, and found many other uses for the space. Fifteen minutes into our school lunch, my friends and I would take a break. A good time to do so, because the nuns went into the chapel just then, to pray for us and the food we were about to eat. ‘All that we have is all a gift. It comes, O God, from you. We thank you for it.’

I was very thankful. For the food. For the break. For the cigarette too. At first, I tried to hold the smoke in my mouth, to let it cool down, that’s what my friend Jen told me to do, but something got set off in my throat and I began to cough. Try again, she insisted. I tried, but started coughing again. It was pointless. She rolled her eyes. Try again till it hits your lungs, she said. I took another drag. Another cough. I took yet another drag, a long slow drag, squinting my eyes like I had seen them do in the movies. I began to feel dizzy. I wanted to give up. But with the next drag I began to feel light-headed and hazy. And I liked it. And at that very moment, I felt my earth tilt beneath my feet.

Mumbi! I don’t remember how the cigarette disappeared from my lips. I do remember how foul my mouth tasted as I sat in the principal’s office. Water, I thought, even as I heard Sister Paula on the phone. Within minutes, Sister Elizabeth, my history teacher, stood beside Sister Paula by the mahogany desk, consoling her, as if it was she who had inhaled the impious smoke. We called them Siamese twins because one could not be seen without the other, and sometimes they finished each other’s sentences, as they now did, expressing concern at my behavior. I didn’t know how long it would take my mother to get here. All I knew was that my head was waging a rebellion against my body’s attempts at calmness.

I get like this sometimes. When the prudence of the outer world crashes into my own, it forces me to dwell inside my head for long periods, fermenting hostile thoughts. My veins swell and my breathing grows more rapid. If I don’t shift my attention elsewhere, there’s no telling what will happen to my insides.

My mother arrived and was greeted with the news of my five-day suspension from school, just before the holidays too, but I just sat there wishing away the smell of smoke from my uniform. Later, in the car, I was overcome by the sniffles, but my mind was more intent on a chance to brush my teeth. My mother may have mentioned all the ways I was going to do right by this world, but my head was making noises of its own and they were much louder than her.

My mother said I was rebellious. My father said I acted wild. I said, the word you’re looking for is practical. I thought that the acknowledgment of a certain pride in my actions would help. It did. My parents took even less time than usual to decide on my banishment.

My parents conferred in whispers through the night and into the early hours of the morning. Sometimes the whispers grew quite loud, and, unknown to them, their words travelled all the way down the white bare walls of the house and into my room. A cigarette is not enough reason, my father said. The countryside will be good for her, my mother replied. It’s just a cigarette, he said. No telling what she’ll do next, she replied, I’m tired of the surprises. Teenagers everywhere are like this, he said. No, Jaji, she said, breaking rules at every turn is not acceptable in this house. Let the rural life teach her to value her fortunate circumstances.

My mother had the last word, as always. I chuckled. She had forgotten that the countryside and I were no strangers to each other.

I had been at Grandma’s house on the outskirts of Hippoland before and after she died. Vast stretches of land. Ants and mosquitos and time, endless time. A shop here and there. The darkness of the night so thick that kerosene lamps and gas lamps and a charcoal burner did little to shed light. Grandma throwing potatoes onto the charcoal, and I bouncing the roasted ones from hand to hand to cool them before the first bite. Corn fields, yellow after shedding the cobs, all around her house. We helped her shell the corn. Later, our hands were covered with a white sap, almost like milk. She left the corn to dry in her front yard. For flour, she explained. The roads were dusty, some had turned to mud. One day our car got stuck. Many helping hands shoved and pushed while my father twisted the steering wheel left and right. The car rocked back and forth. Mito and I had to get out and step into the swamp. Our clothes got covered with mud.

That is where they were threatening to send me now. But I had been there, even if only for a few days, and I had survived.

But when the next day I learnt that I was facing banishment for a whole month, then my mother seemed very cruel. A whole month, away from the Westville cinemas, from the hamburgers and hot dogs, from friends and real life? A whole month—in the dirt and dust and mud? What were we to do?

Intolerable! The night before our banishment, I stayed awake plotting. At midnight, desperate, I woke up Mito. It’s your fault, was the first thing he drawled. I reminded him that we were in this together, regardless. Why did you do it? Accusations. Questions. No answers. I walked out of his room determined to take matters into my hands. But, sadly, by the time it was time for us to leave, I had not yet figured how to free myself from my doom.

A couple of hours before we were packed into our maroon Peugeot, anything that I put in my mouth was instantly expelled, no doubt a sign of what lay ahead. My mother seemed not to notice and kept muttering about how the trip would be good for our culture, and that Aunt Sara was the chosen one to cleanse us of our months of British education from Italian Catholic nuns.

The only culture that awaited us was misery, I wanted to shout, but didn’t.

__________________________________

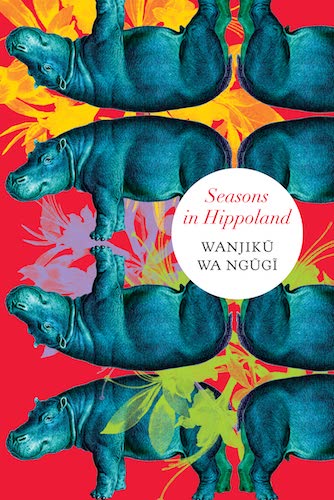

Reprinted with permission from Seasons in Hippoland, by Wanjikũ Wa Ngũgĩ, published by Seagull Books and distributed by the University of Chicago Press. © 2021. All rights reserved.