Searching for Trans Identity in Jewish Texts

Abby Stein on the Struggle to Understand Her Place in Judaism

“What kind of soap are you using?”

I was walking to the mikvah with Eliezer Duvid Schlager, a spiritual adviser who worked with the students. One of his jobs was to turn off the showers at precisely 6 am. There was only one place on campus where we could shower, and if we wanted to shower during the week, we had to make it to the mikvah before 6 am. Only on Fridays, in preparation for Shabbos, were the showers kept on during the day, until 45 minutes before sunset. This meant that students might go days, even a week, without showering. I thought it was pretty gross for anyone to go so long without showering, but it was even worse for a bunch of teenagers going through puberty.

I showered every day. I didn’t mind waking up early, and showering made me feel better. Somehow it made me feel a bit more feminine, more me.

“Um, I use Dove soap and Head & Shoulders shampoo,” I told Eliezer Duvid, showing him the products I had in my hands.

“Really? This is what you are using?” he replied, seeming shocked. “They don’t look or smell like something a Hasidic boy should use. Do you have to use a pink soap bar?” he asked.

I looked down at my soap. “This is what my mother gave me, and it’s what we use at home,” I replied, acting as though I’d never really noticed it before. In truth, I was very much aware that my soap could be considered feminine. But it was something I could get away with, even in an all-boys’ school, and I didn’t feel I needed to defend it.

“Are there any yeshiva rules against using specific soaps and shampoos?” I asked Eliezer Duvid, getting a little annoyed.

“Well, no,” he said.

“Do you ask all the students which kind of soap they use?” I asked him next.

“No, I don’t,” he answered.

“What do you want from me, then?” I asked. He was making me uncomfortable and I wanted him to go away. I was trying to be a good student, but having an adviser smelling my business was not part of the deal.

“Well, I believe in you, you are a rebbishe child,” he said. “I think you have great potential, so I am trying to look out for you, to help you. I also noticed that you shower every day, which is a very girlish thing to do.”

It was the most intense, direct rebuke of Orthodox Judaism I had ever read. It was all I needed.

Of course, I wanted to say, “Yes, I know, that is why I am doing it.” But I couldn’t, so instead I kept my retort simple. “I’m used to it. I’ve always showered every day.”

Eliezer Duvid shook his head and moved on.

I didn’t know where all of that had come from, but one thing was clear. I was under a magnifying glass, and I was not happy about it.

My all-out campaign to suppress my gender identity, and in turn my irreverence for religion and theology, lasted for just a few weeks. Five weeks into the spring 2008 semester, I was back to grappling with my identity. The only explanation I could think of that made any sense was that I was not fulfilling what I came to the world to do, and my thoughts that I was a girl were somehow tied to it.

I decided to ask the Rebbe about it.

As a relative of the Rebbe, it was fairly easy for me to get a private audience with him, even when there were thousands of people clamoring for his attention. So I made arrangements to spend the Shavuos holiday in Monsey, where he lived. I’d stay with Yakov Yosef Hager, the Rebbe’s grandson, and his wife, Shifra, as I often had before. Yakov Yosef would eventually (in 2018, when the Rebbe passed away) become the Grand Rebbe of the Viznitz community in Borough Park, with a following of around ten thousand Hasidic people.

After evening prayers on the first night of Shavuos, I asked Yakov Yosef if it would be possible for me to ask the Rebbe something personal, alone.

“Of course,” he said. “Tomorrow night we are having dinner with the Rebbe at his house. I’m sure you could to talk to him between prayers and the meal.”

On Shabbos evenings and on the first night of every holiday, the Rebbe always had his meal in public, in front of thousands of Hasidim. The second night, the Rebbe ate at home, with family. We all loved that time with the Rebbe; it was one of the few times when our family had the Rebbe to ourselves. It was as if he were a king who would set aside his crown for a time to show that he was also a father and a grandfather.

After prayers that evening, I went to the Rebbe’s house. It was large and beautiful, set on a hillside majestically overlooking the castle-like synagogue. The Rebbe had fallen in 2003 and stopped walking, so there was also a bridge connecting his house to the synagogue, and that somehow made it look even more royal.

At his house, I was welcomed inside, and after a few minutes, Yakov Yosef ’s brother, Chaim Meir, another one of the Rebbe’s personal secretaries, came out of the Rebbe’s study.

“My brother told me you wanted to talk to the Rebbe,” he said. “Now is a good time! The Rebbe is studying before the meal, and he is in a relaxed mood. Go on in.”

I went into the Rebbe’s study. “Git Yom Tov,” I said, introducing myself with my name. “I am Mendel Stein’s child, and I am staying here for the holiday!”

The Rebbe nodded as soon as I mentioned Tati’s name. He knew him well.

“Git Yom Tov,” he said with a smile. “Are you enjoying your visit for the holiday? Where are you staying?”

“I am staying with Yakov Yosef, and everything is great. I’m very happy to be here,” I assured him.

“So, you are eating with us today?” he asked, giving me a loving pat on the cheek, his usual sign of affection.

“Yes, but I also wanted to ask the Rebbe something personal,” I said.

The Rebbe half-closed the Talmud volume in front of him and turned to face me, fully listening.

I cleared my throat. “I am struggling a bit in yeshiva with what to study,” I began. “I mean, there are so many options, so many areas to choose from. How can I know which path is right for my soul?”

The Rebbe looked surprised. A Hasidic master, he was rumored to have been a Kabbalistic scholar, but he rarely used any language of mysticism himself. He clearly was not expecting to hear a 16-year-old ask him questions about the soul.

After a minute of quiet contemplation, the Rebbe spoke. “The Zeide used to say”—the Zeide was his grandfather, Rebbe Yisroel Hager of Viznitz, who passed away in 1936— “the Zeide used to say on the matter of the soul, ‘I am a specialist!’ But he said that about himself, not about me. I do not understand people’s inner souls. However, if you start by studying Talmud, I am sure that the light of the Torah will guide you to the right path.”

This didn’t really help me, but I didn’t say anything more, other than to offer my thanks. I knew it was all he was going to offer. Studying Torah was his solution for many problems, like a nurse prescribing painkillers without looking for the root of the problem.

I was on my own again.

The next few months were a roller coaster of thoughts and feelings. I tried to immerse myself in studying, and instead found myself sick and depressed. I developed intense sinus problems, which I’d had before, but they strangely seemed to grow worse when I was especially unhappy. It was as though my body was responding to the trauma my brain was feeling by shutting down physically.

I developed a cycle that I repeated over and over.

First, I would try to immerse myself in studying. Then, my thoughts about being a girl would return, and I would turn to philosophical questioning, trying to convince myself that I was only having these thoughts because of my religious disconnect.

Then I would decide that I did not believe in any of the religious teachings at all, and my anxiety would surge, as I saw no way out.

After that I’d fall into depression—and develop a sinus infection. Having an infection meant I needed to see a doctor, which gave me the perfect excuse to leave campus and take a two-hour ride to Brooklyn. The doctor would confirm I had an infection, give me antibiotics, and tell me to rest for a day—the perfect excuse to stay home, in bed, where my depression wanted me to be anyway. I would take the antibiotics, and as soon as I started feeling better, I would go back to yeshiva refreshed. Then I’d attempt to immerse myself in studying all over again.

The cycle repeated as many as eight times, each cycle taking about two weeks.

In the middle of all this, I finished reading the forbidden books I snuck into yeshiva. My philosophical questions shifted from my discomfort with religion to evolution, creation, and the origins of the Bible and religion. I craved more words, more ideas. There was a student in yeshiva, Duvid Rubin, who had a connection with a Hebrew bookseller in the Catskills, and he said he could get me any book in Hebrew. I asked him for two more books by Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene and The Blind Watchmaker, which had both been translated from English in the 1990s. I finished both in a matter of weeks.

There was another book I read, too, this one from the yeshiva library. It was called The Book of Knowledge and had been written by an Ultra-Orthodox author who claimed to also be a scientist. He tried to show how science and Ultra-Orthodox beliefs went hand in hand. The book itself didn’t interest me—only a small footnote within it did. It mentioned a former Israeli rabbi named Yaron Yadan, who had become an atheist. In the book, the author wrote that all of Yadan’s arguments were wrong, and so were his commentaries on the authenticity of the Bible and Judaism.

I had never heard Yadan’s name before, but I knew I wanted to read his writings. So I told Duvid Rubin I was looking for any books by Rabbi Yaron Yadan, an Israeli scholar of Jewish law. I also told him that because Yadan was not Hasidic, no one could know that I had asked him for it. I think Duvid appreciated a good rebellion when he saw it, so he agreed to keep it quiet.

A few weeks later, Duvid came over to my room one night just before lights out and handed me a bag. “Here is the book you wanted,” he said. “At least I think it is.” It was a book by Yadon that had been published just a few months earlier. Its Hebrew title translated roughly to Religion Defies Its Creators. The book dives into the depths of Judaism, showing how it is man-made, and how its teachings are backfiring against religious people.

It was the most intense, direct rebuke of Orthodox Judaism I had ever read. It was all I needed.

I am finished with Judaism! I decided.

Not that it was so easy to be finished. To not practice our way of life meant leaving it—I couldn’t stay at yeshiva, or live in Williamsburg, and not follow the practices of our community. But leaving the community would be a radical move; whenever someone did that, which only happened rarely, it was widely demonized. The belief among Hasidic people was that to leave was to live one’s life as a failure, a criminal, mentally ill.

But I knew it was possible. My cousin Luzer Twersky had left the community not long before, becoming the first person in my family to fully leave the Hasidic community. The family had been stunned, and we were told a load of stories about how damaged he was. I didn’t care. I just had to figure out how I could get away, too. I would have to bide my time.

One day, in the beginning of the winter semester in 5769 (2009), as I was browsing the yeshiva library, I found a small book on the bottom shelf. It was simply named Hassidism???

The book was a stinging rebuke of modern Hasidic culture. It made fun of Hasidim who think that Hasidic Judaism is all about the clothes they wear, the specific songs they sing, and the laws they enforce. I could relate to it immediately. I finished the book and found three more by the same rabbi.

I read the three follow-up books. In one of them, called Hassidism!!!, the author goes into detail about what Hasidism is really about. He speaks of the beauty of the holidays, the importance of spirituality above the letter of the law, the purity of intentions, and the great value of happiness.

I loved it.

The author’s name, Reb Yitzhak Moshe Erlanger, sounded familiar, and I remembered that Tati had his books at home.

“I just read four of Reb Yitzhak Moshe’s books,” I told Tati when I spoke with him next. “I really loved them! I really feel like he is speaking to me.”

“Wonderful,” Tati said, “I like his teachings, too! I have many of his books at home.”

It was still not enough to keep me religious, but it was a start.

A few weeks later, it was time to go home for the semester’s Shabbos visit. It just so happened that Reb Yitzhak Moshe would also be in Williamsburg that weekend, for his yearly visit to his followers in New York. Tati got his secretary’s phone number.

I called the number, hoping to make an appointment, feeling not a little desperate. If there is anyone who can save my Judaism, it is Reb Yitzhak Moshe, I thought.

“Reb Yitzhak Moshe is busy today, and I doubt he will have time to see you. Maybe try again next week,” his secretary said.

“But I study outside of the city, and this is my only chance!” I pleaded.

“Well, come by at ten o’clock after evening prayers, and you can talk to Reb Yitzhak Moshe when he eats dinner. You’ll have half an hour,” the secretary relented.

“I’ll take what I can get! Thank you!” I showed up. We talked.

First I shared my background a bit. He remembered Bobbe Stein’s father, who was the Spinka Rebbe in Jerusalem. Soon, though, we were delving deeper into my questions. I told him I’d read his books, and about the impression they left on me, and the struggles I still had. I didn’t tell him about my feelings of being a girl, of course, but I did say I felt untethered from my Judaism.

For the first time, after sixteen years, I had found a text that justified my existence.

What was supposed to be a half-hour conversation lasted almost five hours. At 2:30 am, I finally left, with a clear message from Reb Yitzhak Moshe: “Dive into Kabbalistic studies. It will help you!”

I had nothing to lose.

Reb Yitzhak Moshe told me to start with two books in particular, both of them from the writings of Rabbi Chaim Vital, the 16th-century mystic who had written down the teachings of Rabbi Isaac Luria, known as “The Lion”—the father of modern Kabbalah. One was The Treasures of Life, an introduction to mysticism; the other was The Door of Reincarnation, a study of human souls and their place in the world.

The first book was helpful, even enlightening, but it didn’t offer any real clarity about my own life. I opened the second book and began to read.

It was early on a Friday morning that winter when I reached Chapter 9. The chapter focuses on the gender of souls, and how different souls may enter different bodies throughout time.

I was sitting at my usual place, at the table mounted to the eastern wall of the study hall. There were only a few other students in the study hall at that hour, and the room was quiet. In front of me was my book on my bookstand, which I’d been reading in the dim light, drinking a cup of Taster’s Choice as I turned the pages.

In Chapter 9, I read:

“At times, a male will reincarnate in the body of a female, and a female will be in a male body,” the words jumping up from the page in front of me.

I froze. I read it again. And again. And again.

For the first time, after 16 years, I had found a text that justified my existence. Maybe I wasn’t crazy after all!

I stood up from my chair and left the study hall, walking outside into the cold air, into the forest, where I cried like a baby.

__________________________________

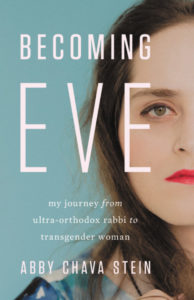

From Becoming Eve by Abby Stein. Used with the permission of Seal Press. Copyright © 2019 by Abby Stein.

Abby Stein

Abby Stein is the tenth-generation descendant of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of the Hasidic movement. In 2015, Stein came out as a woman, and she now works as a trans activist. In 2019, she served on the steering committee for the Women’s March in Washington, DC, and she was named by the Jewish Week as one of the “36 Under 36” Jews who are affecting change in the world. She lives in New York City.